This past October, in Baltimore, high school students had to show proof that they were fully vaccinated against COVID-19 or submit to weekly testing, in order to play sports. While Baltimore has made that call, the story is different in other neighboring districts, like Cecil County and Allegany County, where public schools are not asking for vaccination status or doing surveillance testing of any kind. Like many states across the U.S. there are no longer unified COVID protocols. Decisions on vaccine and mask mandates, events, field trips, and even if parents are allowed in school buildings are left to the individual school districts to decide.

In September 2021, Maryland’s health secretary said that the he was deferring the decision on COVID-19 vaccine mandates to the schools. “We’re being very careful not to be intentionally overbearing and allowing school systems to take the lead in their individual jurisdictions,” Dennis Schrader told The Baltimore Sun.

Will COVID-19 be added to the list of required childhood immunizations?

Debates have flared up over the last several months around COVID restrictions like masking in schools. But as more districts are relaxing or rolling back various COVID restrictions, experts agree: if schools wants to return to normal even as COVID-19 continues to circulate, then students need to be vaccinated. Still, around the country, public officials are abdicating the responsibility of adding COVID-19 vaccines to the list of mandatory vaccinations including measles, mumps, rubella and chicken pox that all students in the U.S. must get to enroll in public school, because of the on-going political controversy surrounding vaccine mandates.

“I think what will happen is that you’ll start to see mandatory school vaccinations requirements just like you do for every other vaccine preventable disease,” says George Rutherford an epidemiologist and pediatrician at the University of California San Francisco. “This obviously becomes much more fraught in certain states.”

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention recommends school’s promote vaccination against COVID-19, but has stopped short of calling for vaccination mandates against COVID-19. For children, Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine is still under an emergency use authorization and hasn’t been fully approved. In the absence of federal guidance, states are divided. Twenty states, all with Republican governors, have outright banned proof of vaccination requirements, according to Ballotpedia. Meanwhile, two states, California and Louisiana, and some pioneering school districts, including Cambridge Public Schools in Massachusetts and San Diego Public Schools in California, are charting ahead and requiring students to get the shot. But sentiment surrounding the vaccine remains tumultuous and rates of vaccination among school children is low: only 25% of 5-11 year olds and 57% of 12-17 year olds have received both doses.

Over the next few years, schools are likely to add COVID-19 vaccines to their roster of usual vaccinations. But in the mean time, schools may have to continue to rely on screening, masking, testing, and other measures to ensure kids stay safe in school. Which means that schools and parents will likely continue to deal with outbreaks and the quarantines, and abrupt switches to remote learning that come with it.

A long slow road

COVID-19 vaccines are politically controversial, despite having an enormous body of evidence supporting their use. Vaccine hesitancy, which has arisen from a combination of misinformation and distrust in the government, medical community and pharmaceutical companies, may keep politicians from adding COVID-19 vaccines to the list of mandatory school vaccinations. On top of that, even in highly vaccinated communities, children have lower rates of receiving even one dose.

There are a few different reasons why children may not be getting vaccinated. Data from a December Kaiser Family Foundation survey suggests that three in ten parents are concerned about the safety of the vaccines for children. While 63% of parents interviewed felt the vaccines were definitely safe for adults, far less felt the same way about children. Only 43% of parents were confident that Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine was safe for 5-11 year olds. But it’s not just vaccine hesitancy that’s stopping parents from vaccinating their children, access to vaccines is playing a role as is physician support. Of the 40% of parents who consulted their physician about COVID vaccination for their child, a third said their doctors didn’t recommend it for their 12-17 year olds and an even higher percentage didn’t recommend it for their 5-11 year olds. The survey also noted that not all schools are actively recommending that students get vaccinated. This data taken together suggests that another reason for lower vaccination rates among children may be that there’s been less of a public health emphasis on getting them vaccinated.

Baltimore City Schools does require school staff to be vaccinated. However, Cleo Hirsch, Executive Director of the Baltimore City Public Schools COVID Response says, it’s not clear to hear whether the community would support a vaccine mandate for students. “Baltimore is very much a city of neighborhoods,” says Hirsh. “We have communities that I think would unequivocally support it. We have communities that would unequivocally oppose it and there is a lot of historical reasons why different communities in Baltimore have more or less trust in medical institutions, in government institutions, and rightfully so.”

In the few districts that have added COVID-19 vaccines to their list of mandated immunizations, it is far from a popular choice. Even in the places that have imposed a vaccine mandate for all students, the rule is won’t take effect until the Food and Drug Administration fully approves Pfizer’s vaccine for age groups 5-11 and 12-17. In the mean time, individual school districts through out California are enacting their own vaccine protocols. Both Los Angeles and San Diego counties have delayed COVID-19 vaccination requirements until the fall.

Even with mandates in place, raising rates of vaccination among students has been slow going in some places. Louisiana’s rule went into effect February 1st and still only a fifth of 5-17 years olds have been fully vaccinated, according to state data. The data shows that some regions, even with mandates, may take longer to vaccinate. Los Angeles county is a bright spot: 84% of children 12-17 have received at least one dose of the vaccine, though only 34% of 5-11 years old have gotten their first shot, according to public records. As is Cambridge Public Schools, where only .2% of students in kindergarten through 5th grade are unvaccinated. Still, in December, the Los Angeles Unified School District decided to postpone enforcing its vaccine mandate until the fall, because it would have meant forcing 27,000 students to attend classes online. Until then, it’s providing incentives to get vaccinated, like dropping the mask mandate for students who are fully vaccinated.

History as a guide

Historically, vaccine mandates have come into effect slowly. For example, we now regularly immunize children against measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR). The CDC writes that in the 1950s measles caused about 48,000 hospitalizations and around 500 deaths annually. Two measles vaccines were licensed in 1963. But by 1969, only seventeen states had added MMR to its list of mandatory vaccinations. It took another decade for all 50 states to adopt it. In doing so, the U.S. was able to wipe out measles for 19 years. Because COVID has had a more dramatic impact on the country than MMR, it’s likely that things will move more swiftly. Still, following a timeline would mean that all the kids currently in K-12 would graduate before seeing a nation-wide COVID-19 vaccine mandate for public schools.

“I think that the American public may need a little bit more time for our youngest vaccine eligible,” says Julie Swann, a professor at North Carolina State University who conducts research on disease transmission and health infrastructure. She notes that there’s been less emphasis on vaccinating children from public health officials. “We didn’t run mass vaccination clinics for children in the way that we did for adults,” she says.

When will school be normal again?

While sufficiently vaccinating U.S. children may take time, schools are thinking about other ways they can make in person learning feasible, even as kids and adults continue to get infected. While health officials may want children to continue to mask, school districts are trying to weigh the cost benefit ratio of masking for students and there is no consensus. California is keeping its mask mandate in place for schools for now; New York City is doing away with mask mandates. Edweek reports that as of March 1, five states currently ban mask mandates in schools, while another eight states still require students to wear masks.

If vaccination rates remain low and masking goes away, schools may become easy sites for disease transmission if a new highly transmissible variant emerges. Swann is concerned that there will be a new variant of concern by the fall that will lead to swelling infection rates. “The extent of the surge will depend not only previous transmission but especially on vaccination status. Vaccination rates are still quite low among students 5-11 and above, especially in some states or counties,” she says. “Our research shows that transmission in schools also impacts communities, increasing community rates by 10% or more.”

Like many states, Maryland has now lifted its mask mandates for schools, leaving the decision as to whether students should mask in the hands of individual school districts. “If you talk to literacy experts and language acquisition experts, they will tell you that masking has a cost and if you talk to public health officials, they’ll tell you that masks are effective,” says Hirsh. “That’s the balancing act that district leaders are gonna have to do.” While other school districts in the state have moved to make masking optional, Baltimore is still asking its students to mask, for now.

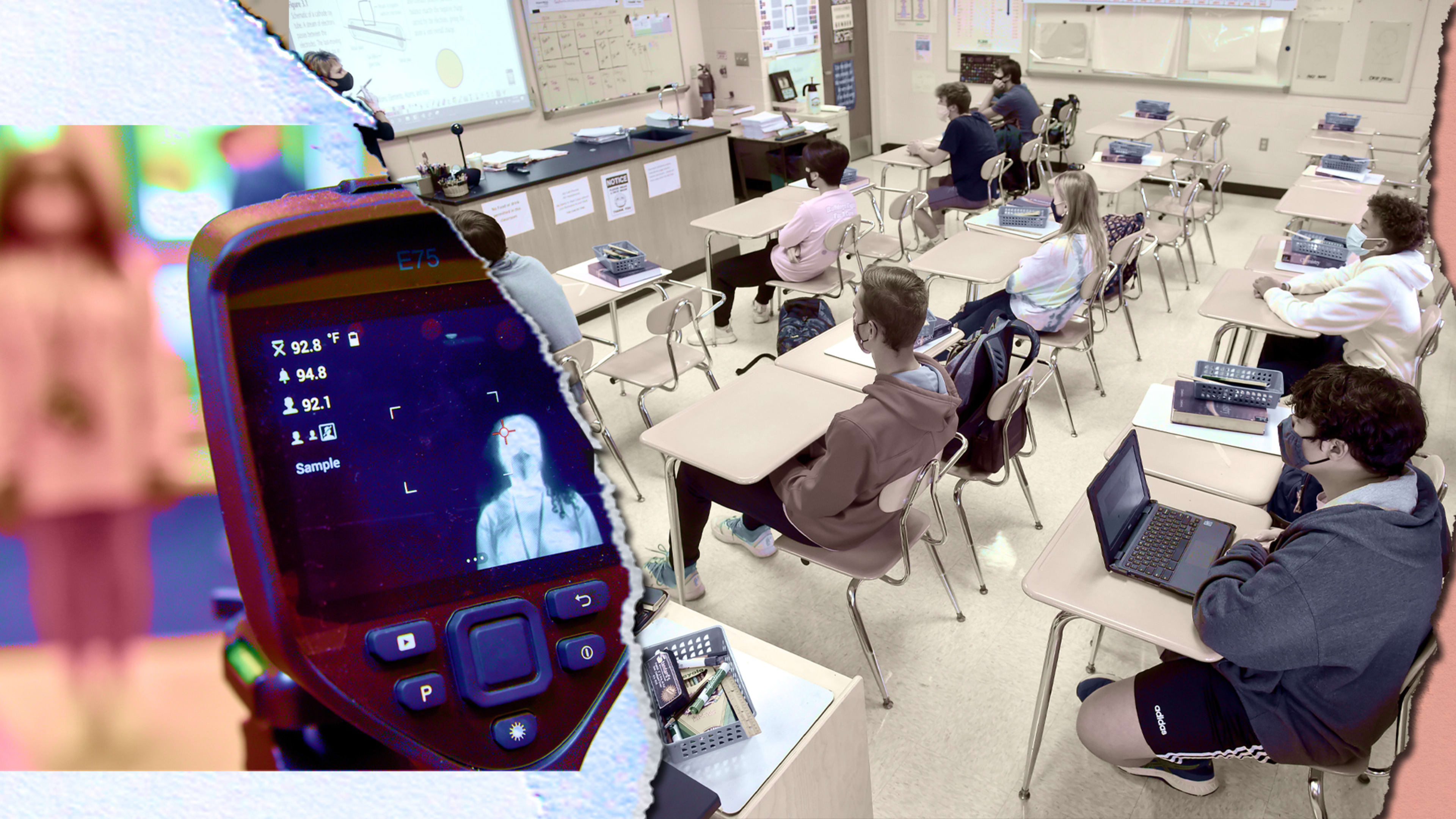

The city has also invested in a variety of infrastructure beyond masking to ensure it can continue in person learning. Baltimore City Public Schools do a combination of weekly pooled testing and individual testing as a way of surveilling transmission. Kindergarten through 8th grade do a weekly pooled test to spot COVID-19 infections within classrooms (student groups that test positive then have to do antigen tests to find the positive cases). High schoolers do weekly asymptomatic testing using saliva based PCR tests. Baltimore City Public Schools has also updated its filtration system and contracted with a company called K Health to connect families with online urgent care.

This level of testing is likely to go away eventually, but Rutherford thinks COVID-19 testing in schools will remain an important part of disease mitigation in the future. “What I’d like to see with school nurses—if they have school nurses—will have test kits at their disposal and they’ll be able to test kids who are symptomatic in order to exclude them more readily,” he says. “I suspect we may not have quite the threshold for closing schools that we do now.”

For now, Hirsh is thinking about how schools can start inviting families back into buildings. “Back to school night just hasn’t happened for for two years,” she says. In Baltimore city, the school is often the center of that community, she says, and therefore has an opportunity to educate vaccine hesitant families in partnership with experts at neighboring institutions like Johns Hopkins University, University of Maryland, and Morgan State.

Schools have long been involved in doling out vaccinations. Massachusetts became the first state to enact a school vaccination requirement for smallpox in 1855. During the polio epidemic, schools played an enormously important role in both helping to find participants for vaccine clinical trials and in educating parents about the vaccine once it was available. Hirsh is thinking about how her schools can similarly act as hubs for public health education.

In events like Back to School Night, she sees an opportunity to connect with families and even use the school as a public health education resource. “What are the actual health benefits of reopening those doors and welcoming the community back in, so that you can build those relationships and have those conversations to meet people where they are and then get people on board with whatever the next steps are to help us move towards COVID becoming more endemic,” she says.

But she’s also thinking about making school normal again. Prom is coming up this spring as are graduations. “We’re trying to create rules that allow kids and families to experience those things again, because those are things are so important for childhood development and for community building, for making memories and for making school communities robust.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.