Three and a half years ago, on a walk home from work in Kabul, Afghanistan, Sara Wahedi narrowly missed being struck by a suicide bombing, part of an attack that ended up lasting hours. In the aftermath, with the streets blocked and broken glass everywhere, Wahedi was struck by the fact that she couldn’t find information about what had happened—or when roads would open or the power would come back or whether it was safe to go outside.

“It led me to wonder why an alert system didn’t exist in a country like Afghanistan, which has been crippled by instability over the last two decades, and with so much money going into social development and community development, how there wasn’t something that people could turn to to find verified, real-time information about security and city services,” she says.

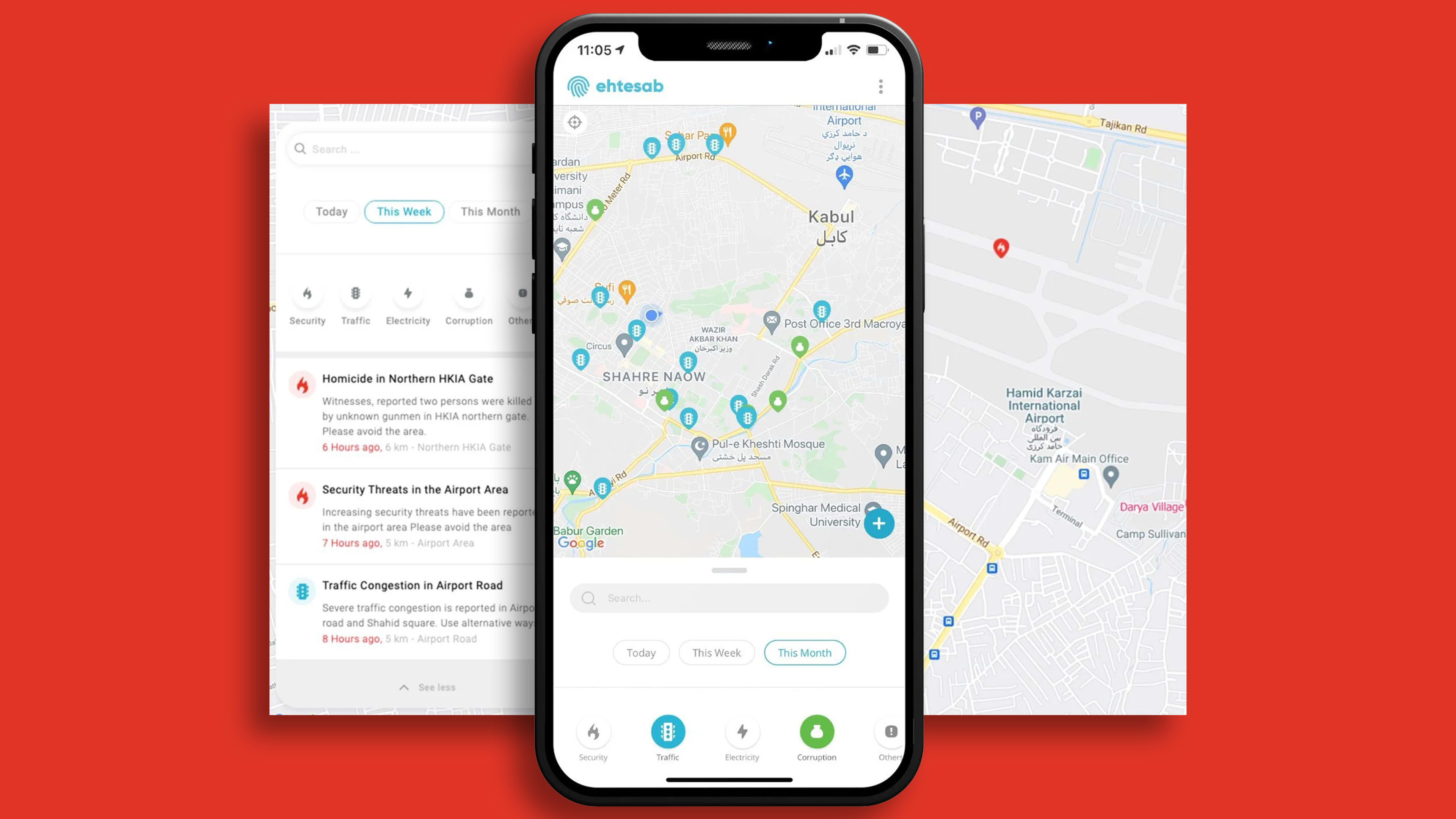

“We designed it to be as simple to use as possible because it’s a crisis app,” she says. When the app opens, there’s a button to send a report if someone is witnessing a problem, ranging from at attack, to a street blocked by garbage, to a power outage. There’s also a map that shows current alerts, and an option for push notifications. The alerts are sent to anyone in Kabul, without tracking the user’s location—unlike Citizen, an American crisis alert app—because tracking someone’s location could be dangerous if the data falls into the wrong hands.

In the U.S., Citizen has been criticized for creating a culture of fear by sending a constant stream of alerts about crimes. In Afghanistan, the situation is different; Wahedi says that using Ehtesab can make people calmer. “Where uncertainty is the ruler, you want to be certain,” she says. “You want to know what’s going on.”

The app is expanding to two other cities in Afghanistan next month. Ehtesab has also had requests from people in Africa and South America to create local versions of the app. It’s been a challenge to get investors, she says, but she wants to expand.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.