Quarantine is uncertainty in built form, according to authors Geoff Manaugh and Nicola Twilley. Throughout history—and likely into the future—uncertainty about the safety of people, objects, plants, and animals has required architectural responses to keep the world protected. Long before COVID-19, a wide range of structures and systems were devised to isolate that uncertain risk. And as Manaugh and Twilley show in their new book Until Proven Safe: The History and Future of Quarantine, containing risk is a process unfolding all around us.

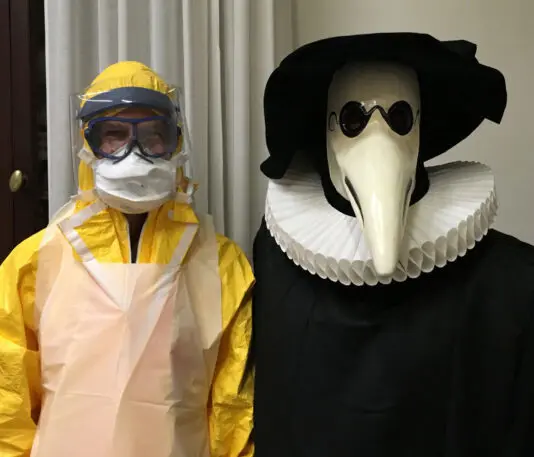

After several years of traveling to ancient Black Plague quarantine fortresses built on the Adriatic Sea, and visiting modern isolation and quarantine facilities for people, plants, pathogens, and spacecraft, their book had the last-minute addition of one real life quarantine-inducing pandemic. Through a mix of globetrotting journalism, narrative nonfiction, and a deep historical look at how quarantine has been used over centuries, Manaugh and Twilley’s book shows how quarantines are likely to continue to be part of our world, even in the unlikely event this is the last pandemic we see.

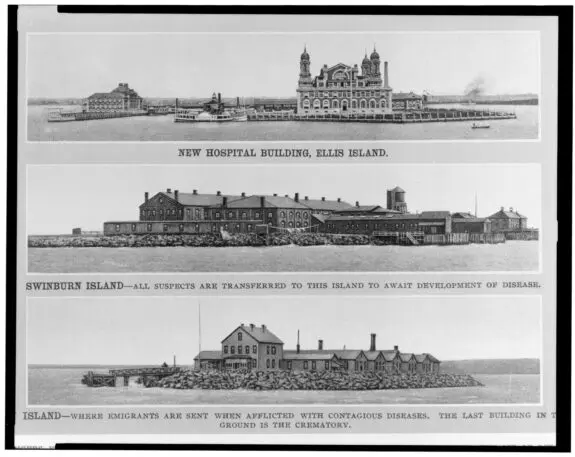

Geoff Manaugh: An origin point for the book was seeing a quarantine station that had been converted into a hotel when we were traveling in Australia in 2009. Quarantine had always sounded like this really strange thing that they used to do, a historical process or activity that really had no place in the modern world. Quarantine hospitals were now in ruins, or they’d been converted to other uses, or they’d just been torn down altogether. And even the idea that you would have to quarantine instead of getting a quick shot or a vaccination just seemed so obsolete. Initially our interest was to look at what happened to quarantine. What was this thing that produced architecture all over the world? And that led to the design and construction of facilities and hospitals and these really strange buildings in really remote places. What was that activity of quarantine, and where did it go.

Of course literally within instants of asking questions like that you realize—and this is what inspired the belief that we could do an entire book on this topic—quarantine didn’t really go anywhere because it went everywhere. Now you can see it’s not just in hospitals or port cities, it’s in the food supply, it’s in the way that astronauts return to earth from the International Space Station, it’s in how we deal with global pandemics like COVID-19. The original impetus to explore it was the realization that something we thought was obsolete and historical was in fact ubiquitous and incredibly important.

Nicola Twilley: That is something you see again and again. One place we saw it was Ancona, which is a port on the Adriatic coast of Italy. It was the Pope’s free port on that side, and they built a spectacular lazaretto, or quarantine facility. It’s still an astonishing building today, sort of a giant pentagon with this incredible faux temple structure in the middle. Obviously quite an investment, and they thought it was going to be a great way to protect the city from the plague. But by the time it opened up, there were no more major outbreaks of the plague and it was never really used for its purpose. And that was a story we heard again and again.

I think one of the most striking examples was, in early 2019, we went and visited the first federal quarantine facility that had been constructed in the U.S. in more than a century, in Omaha, Nebraska. And it had 20 beds. Super interesting design from an engineering perspective. All the separation and engineering controls that in the past would have been accomplished by putting a quarantine facility on an island, now allowed quarantine to take place in the middle of the country. But for only 20 people. And that’s because it was designed thinking that in the future we would only need to quarantine people coming back from a place where there might be an Ebola outbreak or something like that. And the architecture reflects that. When we caught up with Ted Cieslak, who runs that facility, during COVID-19, it was clear that no one had really thought through what mass quarantine would look like for a respiratory disease that spreads much more easily. So it’s a constant, designing for the last pandemic, and you get these buildings that were produced for the disease before them. They embody how to control the last disease.

It’s probably common right now to think of quarantine for people, but it’s used more often for pathogens and plants or crops—things like wheat rust or cocoa plants or suspicious houseplants at state border crossings. How do those spaces and processes differ from human-related quarantines?

NT: Part of our goal with looking at these other forms of quarantine was to say, “what can we learn from quarantine by seeing how it operates in these other contexts, detached from the human ideas we bring to it?” With plant and animal quarantine, you really see the calculus of the potential risk and the potential harm to trade spelled out in very stark economic terms. At its heart, quarantine was an attempt to preserve the economic benefits of trade while not all dying. So in the plant world that calculus plays out much more stripped of the concerns we have about human life, because you’re just talking about plants. To see how these decisions are made in different fields, how the spaces are constructed, what the overlaps are, it allows you to see the underlying assumptions and calculations that go into quarantine decisions stripped of some of the layers of human history and assumptions that might otherwise cloud your vision.

The other piece that I think is just super fascinating is how other animal species quarantine and what we can learn from them. And that’s an emerging field right now, but just as ants and termites and so on have been building architecture longer than us, they’ve also been social species dealing with the risks, the tradeoffs, the benefits of mobility and disease. So it seems possible that we can learn to isolate and quarantine from them also.

GM: A lot of it comes down to questions of communication and trust. If you don’t have trust in authority or in expertise, it’s very difficult to maintain anything like quarantine or zones of safety because people won’t believe you that the risk is real. And we saw that during COVID-19 where huge sections of the population didn’t necessarily believe that it was a real disease, and then didn’t believe that the vaccine was real. So if you don’t trust the experts saying “don’t open this” or “don’t go in there,” then you’ll never be able to maintain a site of quarantine effectively. Even in the Black Death, communicating that this is a site of risk or this is a place of danger, referring to a quarantine house or a house that had disease in it, was not easy. Burglars or people who had recovered from the plague and were immune to it took that to mean that they should actually break into that house because nobody was there and it would be easier to get in. Those are major challenges that are beyond architecture.

NT: One of the things that I still personally find hard to recall is that quarantine is inevitably leaky and yet it still works. In fact, you should know it’s leaky going in and still impose it and follow the rules. That was one of the things that came very clearly out of the research that the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) had done, that a quarantine is always leaky and it still works because you’re reducing interactions. It’s not an all or nothing thing, and that’s what makes it hard. It’s this gray space. It doesn’t have the charm of certainty and that’s what makes it so slippery and also so fascinating.

There’s also a somewhat disturbing technological angle here about the future of quarantine being programmed into the built environment. What would that be like, and what is it already like?

GM: Differential access to infrastructure is already a kind of quarantine and certainly lends itself well to quarantine. On an urban scale, I think you’re already seeing a kind of filtering of who can go into particular spaces at different times as a form of social distancing or quarantine. But what we tried to show in the book is it’s going to become more or less indistinguishable from the “smart homes” of the future. If Google is already tracking what you’re searching for online and they also own the company that runs your thermostat and they know you’re searching for flu remedies and you’re also cranking up the heat in your house, there’s a pretty good chance that you might have the disease that happens to be passing through that region. So it doesn’t seem like much of a stretch when Google also owns the company that runs your front door lock, that there might be an opportunity for public health and big data and algorithmic health care to overlap in this strange, I’d say quite ominous, world where your house can make the decision that it’s going to quarantine you whether you want to stay home or not.

NT: This trend is not new in history. You can trace the ancestors of today’s passport, which is a piece of paper that restricts or facilitates your mobility, that has its origins in a health passport which was an invention during the Black Death to help people avoid having to spend time in quarantine. These things have hardened into place before, so it’s not paranoid to think that they will again.

GM: It sounds very dystopian and pessimistic, but on the opposite approach, it was really interesting to talk with Todd Semonite, who is the former chief engineer at the Army Corp of Engineers, about the possibilities of building quarantine into our infrastructure, into our sports stadiums, into our hotels, our convention halls, our dormitories, even our private homes. We have an opportunity to make quarantine less onerous in that our houses can already do it. So it’s not that we’re just going to get locked in by Google, but that the air conditioning systems in hotels can be tricked into operating in a particular mode that allows us to not be contaminated by the person in the room next to us. Our dormitories can be converted into quarantine facilities so that we don’t all have to leave campus the minute a virus breaks out. Airport hotels can simply turn into places for medical isolation so that cities or countries don’t have to rely on what we saw during COVID-19, where military hospital ships were being sent to New York City or U.S. citizens were being held on military bases as a way to prevent them from going home after they got off a cruise ship. So the positive version of this is that quarantine will just be sprinkled throughout the built environment and it won’t be something we have to panic about.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.