If you’ve ever heard a bird sing and wondered how you could possibly figure out what type of bird it could be without laboriously searching through recordings, The Cornell Lab of Ornithology now has you covered.

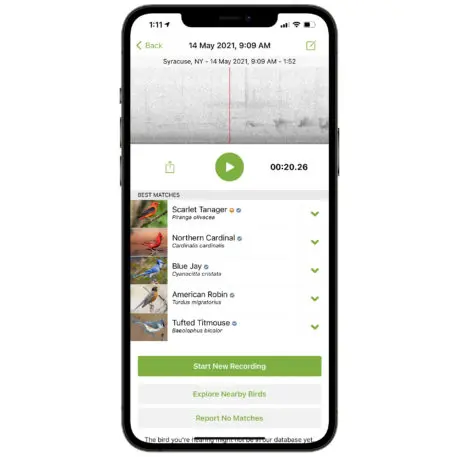

The lab recently upgraded its Merlin smartphone app, designed for both new and experienced birdwatchers. It now features an AI-infused “Sound ID” feature that can capture bird sounds and compare them to crowdsourced samples to figure out just what bird is making that sound. Since the feature launched late last month, it’s become the most popular feature in the app (which also features AI tools to identify birds in photos), and people have used it to identify more than 1 million birds. New user counts are also up 58% since the two weeks before launch, and up 44% over the same period last year, according to Drew Weber, Merlin’s project coordinator.

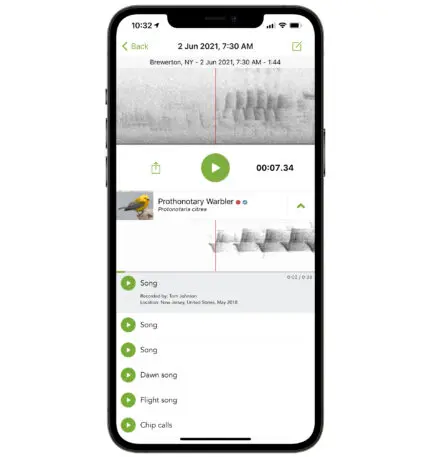

Even when it’s listening to bird sounds, the app still relies on recent advances in image recognition, says project research engineer Grant Van Horn. When you ask the app to record sounds around you and scan them for bird calls, it actually transforms the sound into a visual graph called a spectrogram, similar to what you might see in an audio editing program. Then, it analyzes that spectrogram to look for similarities to known bird calls, which come from the Cornell Lab’s eBird citizen science project.

The goal is to identify plenty of audio samples without generating false identifications. But some birds are easier than others to identify, Van Horn says.

Birds like blue jays and mockingbirds that imitate the sounds of other birds are naturally more challenging to conclusively identify, but the team does have ways to improve the app around tricky birds. When there are issues identifying particular types of calls, they can look for additional samples of that bird, ask an expert to confirm that they are indeed correctly classified, and add them to the training dataset.

The app isn’t the only one to function as a kind of Shazam for birds, but it is completely free and assures users that it doesn’t submit their audio data to any central server, although Cornell may offer the option to share samples in the future. Instead, all the processing is done on users’ iOS or Android devices, which both safeguards privacy and ensures that people can use the app on hikes or in other places with limited cell reception (although you do need to let the app download a dataset for your region the first time you use it in a particular region).

At the moment, the team is working to further perfect the model before next spring, when birders are likely to take to parks and trails hoping to identify migratory birds on their way north. One challenge will be making sure the app can handle multiple overlapping bird calls at a time when birds will be particularly plentiful. Cornell’s designers will also continue to work on handling birds that the app has a hard time recognizing. That includes one species—plentiful near Van Horn’s Ithaca, New York, home base—that he theorizes may be so common in the background of recordings of other birds that the AI has effectively learned to tune it out.

“It takes a long time for the app to make a suggestion on red-winged blackbirds,” he says, “and that’s something I’ll continue to iterate on and try to improve.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the final deadline, June 7.

Sign up for Brands That Matter notifications here.