Kristina Durante was driving in her car one day when “Material Girl” by Madonna came on the radio. It’s a song she’d heard countless times, of course, but not in a long while. “How had I forgotten what a gem this song is!?” Durante thought, as she cranked it up loudly. Later, recalling the thrill of the moment, Durante did what a lot of us would do: She downloaded it, and put it into her music library.

“I played it, remembering how much I loved it,” says Durante. “And when it was on my playlist, I was like, ‘It just isn’t the same.'”

Durante’s story is probably familiar to many of us. Whether it’s a song on the radio, or a free sample at a store, these surprises—these moments of serendipity—make us appreciate the little things so much more than if they were planned. But as a professor of marketing at Rutgers, Durante could do something most of us couldn’t. She and her team enlisted hundreds of people who took part in nearly half a dozen experiments, just to answer that question: Do we really enjoy things more when they’re serendipitous discoveries rather than something we carefully choose ourselves?

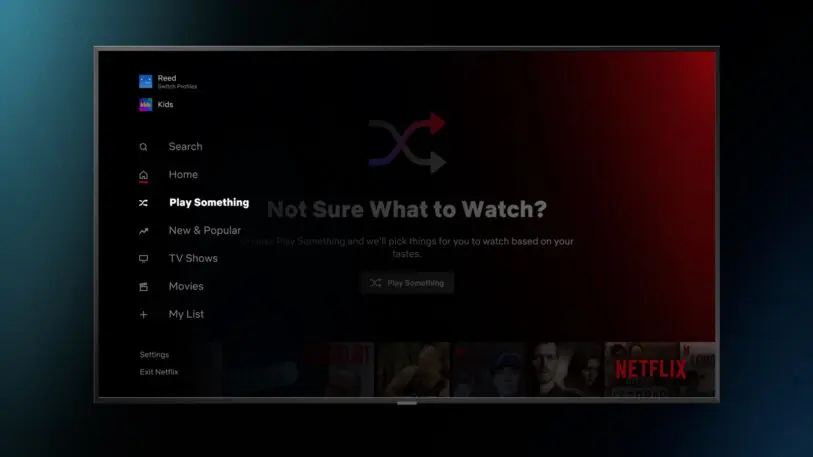

It turns out, we do. And the phenomenon is significant enough that Durante believes that products should be designed around surprise rather than painstaking curation. It’s why she’s a fan of the design behind subscription boxes and Netflix’s new random “Play Something” feature, but she’s not so bullish on dating apps that simply list endless people to meet. The effect of serendipity is “absolutely large enough that people should be designing platforms around it,” Durante says. Though as her new research paper in the Journal of Marketing suggests, there are limits and exceptions to this advice.

The paradox of choice

Most of us have heard about the paradox of choice. While people say they want options and the opportunity to shape their own destiny, the truth is that deciding between a long list of products or menu items can actually cause a lot of stress and make us unhappy.

You can think of serendipity as the antithesis of choice. “With serendipity, you don’t choose,” Durante says, “and you end up liking it more because there’s no engagement in overthinking.”

The impact of serendipity was powerful in testing, offering anywhere from a 10% to a 25% increase in enjoyment and satisfaction of a product or experience. But Durante believes it could be even larger in the real world.

The word “serendipity” is complicated (though Durante says that the 2001 John Cusack film by the same name does a superb job of illustrating the phenomenon). “We [also] call it fate, or chance, or luck. [Serendipity] really hovers around the same core concept,” Durante says. “There’s some ethereal hand that played a role here beyond surprise . . . that adds something more magical when we don’t know how it happened. It wasn’t deliberate, so it must be fate.”

Indeed, when Durante’s team polled hundreds of people about their experiences with subscription boxes like Birchbox and Stich Fix, people reported enjoying the items they received more when they were random than when they actually selected them.

Then in another trial, Durante’s team set up a fake recommendation engine for movie trailers called Movie Trailer Zone—something like the Netflix algorithm for 90-second film teases. The experience was mostly the same for everyone. But some people were told that they were given a personally curated trailer from a list of 10, while other people were told that they were given a random trailer from a list of 100.

Who reported enjoying the trailers more? The people who were told the selection was randomly picked from a big pile, rather than carefully curated from a short list. Why? The random trailer felt serendipitous, as if someone had gotten a lucky surprise.

Durante’s research is fascinating when you compare it to the evolving recommendation strategy of a company like Netflix. The company’s evolution aligns with the findings of the research, even though the research came out after Netflix made its updates.

While time will tell if Netflix’s strategy makes for more satisfied viewers, Durante tells me that more companies should follow suit, building the option for serendipity into their platforms. Such serendipity doesn’t need to be random, either. It just needs to seem random. Because her research suggests that customers will enjoy their products more for it.

The limits of serendipity

The biggest challenge with serendipity is that if someone likes what they stumble upon, they will usually like it more than if they’d chosen it themselves. But if they don’t like what they stumble upon, then the serendipity doesn’t help.

In yet another trial, the researchers showed participants a piece of art. Some people were shown beautiful abstract expressionist works. Others were shown paintings of toilet paper and garbage. Serendipity made people like the beautiful paintings more than if they had chosen them on their own. But serendipity did nothing to help people like the toilet paper and garbage more in any measurable way. “When it’s negative, you don’t want surprise and you don’t want random fate to play a hand in negativity,” Durante says.

Another intriguing phenomenon the team studied was how serendipity affected people with a subject matter expertise. For instance, if you know a lot about smartphones or coffee brewing, would you want a surprise Samsung Galaxy or Mr. Coffee machine?

To examine this topic, people were enlisted to use the service Brain.fm that promises to play music that would enhance their focus. Some people were taught about the correlation of particular brain wave patterns with music and focus, and they were allowed to pick their own track to listen to. Others did not receive this information and were given a song randomly.

In this case, people who chose their own songs were more satisfied than people who had the serendipitous surprise. “The layperson takeaway is, when you know a lot about a product, you really do like to have a hand in that process, and enjoy it more by engaging,” Durante says. The point makes sense. If you know everything about skydiving equipment, then you probably want to pick out your next kit yourself, rather than have someone else randomly cobble together your flight suit.

“I think about Paul McCartney randomly encountering a song, he might not get the same magical boost in enjoyment. Or maybe he would! But that’s the idea,” Durante says. “If we are experts in the category, then [serendipity] might have a boomerang effect.”

The ethics of a surprise

Ultimately, Durante believes that many businesses—though not all—should try to incorporate serendipity into their product strategy. “If you’re a marketer of movies, entertainment, songs, candy, lollipops, and rainbows—those types of things that are trivial but offer benefits in life, then serendipity, and the veiled nature of how we come upon these things is beneficial to our satisfaction,” Durante says.

Of course, some applications make more sense than others and using serendipity in the wrong context could backfire. No one wants surprise surgery, because that’s a serious, and negative, experience. Negativity and serendipity don’t mix. “If you’re choosing between medications or medical procedures, you don’t want serendipity, you for sure want choice,” she says.

The more serendipitous an interaction, the less insight a user has into how and why it was made. That’s fine for movie trailers, but it’s immoral in other contexts. We’ve seen Facebook and YouTube serendipitously recommend great stories and clips to watch. But they’ve also guided us to content supporting alt-right conspiracy theories. By hiding the levers of their algorithms, many big tech platforms create serendipity, but in doing so, they create hostile, opaque systems that are difficult to scrutinize.

“We’re relying on conglomerates and corporations to do the right thing, and as somebody who studies this, I’m not sure that’s necessarily going to happen,” Durante says. “In a perfect world, we could say you have the moral responsibility to provide that transparency for access to information and decisions that are most critical in our lives, like voting and healthcare. But our work shows that for [for companies] to bring some lightness to our lives, we need a little more magic there.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the final deadline, June 7.

Sign up for Brands That Matter notifications here.