The next generation of energy-efficient homes is on its way. Nine new homes have just completed construction in cities across the United States, offering a glimpse of how homes can be green, affordable, and beautiful.

The homes were built as part of the U.S. Department of Energy’s Solar Decathlon Build Challenge, a biennial competition among university teams to design and build houses that push the limits of energy efficiency. With buildings accounting for 74% of national electricity consumption, the need for better-designed homes is huge. Constructed under real-world conditions in communities near their universities, many of the nine homes are now occupied by residents. Like the houses built in previous years’ competitions, they’re test cases for the latest thinking in energy-efficient design.

On Sunday, April 18, Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm announced the winners of the competition, and the prototype homes these teams built demonstrate some of the newest approaches to bringing down energy use in homes and buildings, while still making them affordable to build. Evaluated for 10 different metrics, including energy efficiency, architectural design, innovation, and market potential, the homes had to be as technically impressive as they were feasible to build. This year’s top finishers also happened to explore efficiency strategies for places with extreme climates—the kinds of conditions climate change will make more common for a larger number of houses.

It’s a multifront design challenge that Granholm likened to a much bigger challenge facing designers and builders. “In so many ways our fight against the climate crisis is a lot like the decathlon. We’ve got all these individual contests to get through,” Granholm said. “There are new playbooks in this climate fight on energy efficiency, on renewables, on modernizing the grid, on decarbonizing the building sector, decarbonizing the transportation sector, decarbonizing the industrial sector. We can’t win unless we rewrite them all.”

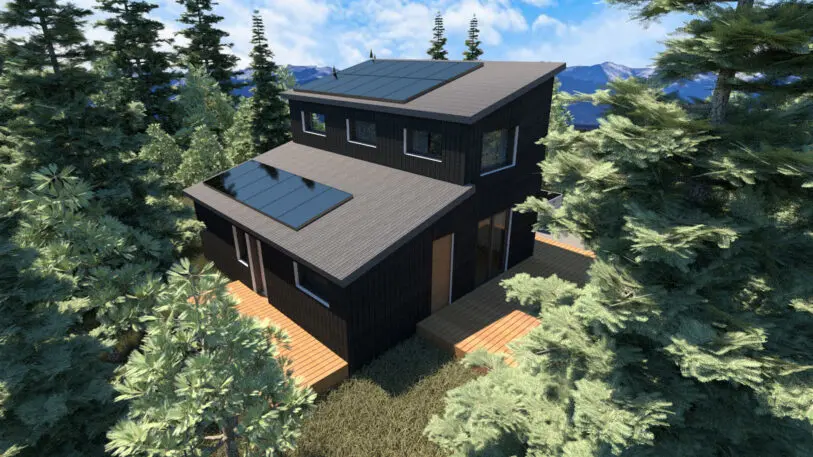

The highest-ranked home in the competition was designed and built by a team from the University of Colorado in Boulder. Their two-story, two-unit house was designed to offer an efficient and affordable alternative to the high-priced houses in the region. Accommodating the cold and snowy climate, the home managed to reduce its estimated annual utilities cost to about 10% of a conventionally built home in the area. Using equipment such as solar-tracking photovoltaic panels, an energy-recovery ventilator that reuses exhaust heat from the home’s appliances, and highly efficient air conditioning through zone-based ductless mini-split heat pumps, the home generates an estimated 321 kilowatt-hours of excess electricity that is stored in on-site batteries. A rentable accessory dwelling unit provides a source of extra income for the owners while adding another affordable housing option for the region’s lower-income families.

The second-place finisher designed a home for an equally harsh climate. Designed and built by a team from the University of Waterloo, the project is an affordable net-zero-energy home designed in conjunction with the Chippewas of Nawash Indigenous community in Ontario. With a fairly straightforward rectangular footprint and classic gabled roof, the house’s energy-efficiency innovations are hidden inside, where a hybrid electric water heater tank and heat pump uses electrical resistance and ambient heat to provide the home’s warm water. Triple-glazed windows and an insulated concrete foundation help the home retain its own heat, using 55% less energy than a conventionally designed home.

On the other end of the climate spectrum, the competition’s third-place finisher is a house in the hot and arid Southwest, designed and built by a team from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. Designed specifically for veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injuries, the house is low on energy, while also providing an accessible floor plan and thick insulation to prevent potentially jarring outside noises from bothering the resident. Designed with PV panels and on-site battery storage systems, the home is capable of powering itself off the grid for up to three days. The narrow rectangular structure also features a small central courtyard that’s shaded from the desert sun and cooled by interior living walls of drought-tolerant desert vines that are hydroponically irrigated with recirculated water.

All the entries were designed and built over the course of multiple years by teams that started the competition in 2019. The process of turning their designs into built prototypes was complicated by the pandemic. Constructed by the student designers themselves as well as some volunteers from Habitat for Humanity, the homes were designed with expert input from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory in Colorado.

Launched by the Department of Energy in 2002, the Solar Decathlon usually brings its top-ranked designs to the National Mall in Washington, D.C., to be displayed to the public, but the pandemic necessitated some workarounds, both for the Build Challenge as well as the larger Design Challenge, which included energy-efficient building designs from dozens of university teams. Instead of physical displays of the houses, the Decathlon has created a virtual tour that allows users to view photos, videos, and 360-degree tours of the insides and outsides of the structures. Tests show their energy performance compared to conventionally designed homes, and some have been able to achieve savings that represent thousands of dollars off residents’ utility bills.

The results are impressive and hint at a near future when buildings represent a much smaller chunk of the world’s energy use and carbon footprint. The Solar Decathlon competition is a testing ground for the new approaches and technologies that can help the broader design and construction industry improve the energy efficiency and environmental sustainability of buildings. Through design techniques as well as a growing pool of young design professionals, the effects of the competition eventually trickle up into the design and construction industry.

In her announcement of the competition’s winners, Granholm celebrated this next generation of energy-efficient housing and also called on the dozens of student participants in the competition to pursue energy-efficient design as a profession once they graduate. The need and the potential, she argued, are massive.

“There are more than 125 million buildings in the U.S. alone,” Granholm said. “We’ve got to find smarter and easier and more affordable ways to retrofit them all, to rethink them, to rewrite the playbook on all of them.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.