When businesses and schools shut down in Los Angeles a year ago for the pandemic, the city’s smoggy skies cleared and rush hour traffic disappeared. Pollution also shrank in other cities. It seemed like a sign of how much climate emissions and air pollution could drop if companies decided to let more employees work from home permanently.

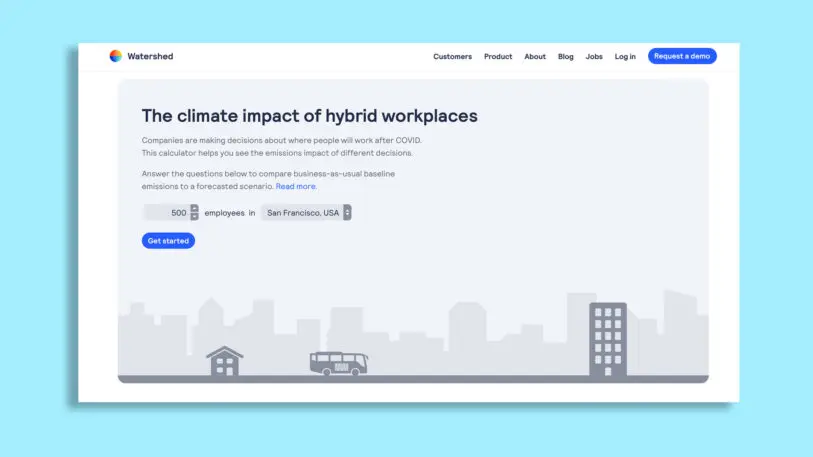

But the benefits aren’t quite that simple. A new calculator lets companies plug in different scenarios in a handful of cities—San Francisco, New York, Houston, London, and Toronto—and see how changes to people’s work patterns and commutes might impact overall emissions.

Unsurprisingly, commutes do matter: In a 500-person office in Houston, for example, if almost everyone who normally drives alone to work suddenly begins working from home, workplace emissions could drop 58%, and the company’s total emissions might fall by 9%. But the details make a difference.

If remote work makes more employees decide to move to the suburbs, their individual carbon footprints could rise because they end up driving more. If an employee moves to a distant state, they might end up taking more long-distance flights back to the office. A blog post from Watershed, the climate software platform that created the calculator, notes that flights make a large difference; for a typical startup with 100 employees, reducing per-employee flights from three to two each year could cut workplace emissions by as much as 20%.

Other factors not included in the calculator also come into play, like the fact that some people working from home might end up ordering more food delivery for lunch instead of walking to a company cafeteria or a restaurant down the block from the office. In a city where most employees were taking the subway or walking to the office—or in a place like Norway, where a longer commute might be likely to happen in an electric car—some other factors might actually make remote work a less desirable option.

“Many people think the climate-conscious choice is to keep as much of the team working remotely for as long as possible,” Watershed writes in its blog post. “The reality is more complicated. Remote work shifts carbon: Emissions from energy and food still exist, but at employees’ homes, where they may be better or worse than in the office.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.