Most of the 360-billion-plus metric tons of plastic manufactured each year isn’t recycled. Some of that’s due to laziness—in the U.S., where plastic bottles can be easily recycled almost everywhere, the vast majority still end up in the trash. But other types of plastic are so technically challenging to recycle that recyclers don’t find it economically feasible. If you put these in the recycling bin, they end up being incinerated.

A new recycling plant is designed to process this hard-to-recycle plastic using what’s called supercritical steam—water heated to a high temperature and pressure—as molecular scissors, breaking down chemical bonds in plastic to create building blocks that can be used to make new plastic. The process works on any type of plastic, including packaging with multiple layers that normally isn’t accepted in recycling bins. “A new solution is needed to recycle those materials that mechanical recycling cannot,” says Steve Mahon, CEO at Mura Technology, the company that developed the technology and is building the new plant. “It is also important to recognize the value of waste plastic as a ready resource for the manufacture of plastic, decouple production from fossil resource and entering plastic into a circular economy, avoiding wasting this useful and flexible material.”

Mahon agrees that plastic reduction needs to happen, but he believes that the technology can fill a critical gap. “With the level of plastic manufacture at an all-time high, we believe that where excessive plastic waste and single-use items can be reduced, they should be,” Mahon says. Mura’s technology, called HydroPRS, is “designed to recycle those materials that traditional mechanical recycling cannot, in a complementary approach, moving away from a linear model of produce-consume-dispose to a circular one of produce-consume-recycle,” he says. The demand from companies that want to use recycled plastic in packaging continues to grow. The new technology will produce recycled products that are more expensive than virgin plastic, but the company believes that it will become cost-competitive within a decade or sooner.

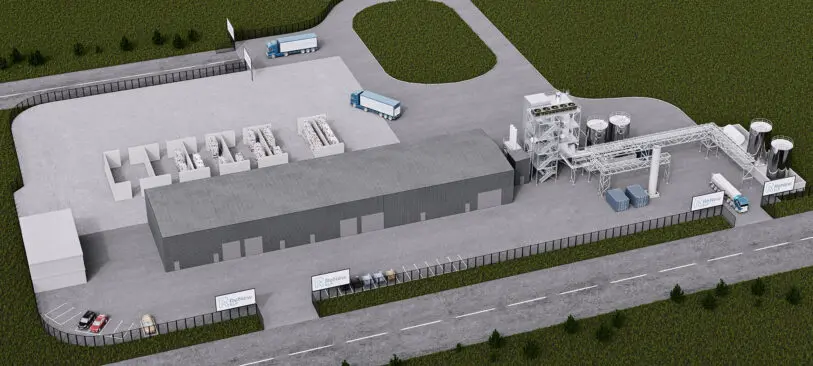

The new facility is set to open in 2022 and is designed to process 80,000 pounds of plastic waste a year. The company is also planning new sites in other countries, including the U.S.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.