This story is part of Doubting the Dose, a series that examines anti-vaccine sentiment and the role of misinformation in supercharging it. Read more here.

Quick—when did the epidemic of misinformation about vaccines begin? Was it when Jenny McCarthy took to The Oprah Winfrey Show in 2007 to claim that a vaccine caused her son’s autism? Or maybe when the anti-vax movement discovered that social networks such as Facebook and Twitter were a powerful way to amp their message and recruit new members to the cause?

Try a little earlier than that—by more than two centuries.

Shortly after Edward Jenner pioneered vaccination at the end of the 1700s, the movement against it began. Even earlier, vaccination’s precursor—known at the time as inoculation or variolation—inspired similar fear and misconceptions.

Some of the specific arguments made against vaccines have evolved over the years. The means used to amplify them—from pamphlets to online videos—have changed even more. But there have also been plenty of lasting themes throughout the long history of vaccines and their opponents, from smallpox in colonial America to today’s pandemic.

As we strive to reach herd immunity to COVID-19—even as surveys show that nearly a quarter of unvaccinated U.S. adults remain hesitant to get the vaccine—it’s worth remembering that we’re dealing with an enduring challenge, not a new one.

1721: An inoculation drive makes enemies

As a smallpox outbreak rages in Boston, famed Puritan minister Cotton Mather becomes an ardent proponent of inoculation after learning of the practice from Onesimus, an enslaved West African, who explains that he had been inoculated in his youth. Typically involving deliberately infecting patients with smallpox by rubbing infected scabs or pus into a skin puncture, inoculation is intended to cause a mild infection—and then immunity. It proves a potent tool against smallpox, but it’s also controversial for multiple reasons, including racist reactions to its roots in Africa and concern that it might be a violation of God’s will.

Widely associated with inoculation, Mather suffers the wrath of anti-inoculators, one of whom flings a bomb through his window. An accompanying note reads, “Cotton Mather, you dog, dam you: I’ll inoculate you with this; with a Pox to you.”

1796: Vaccination is born. So is vaccine skepticism

British doctor and scientist Edward Jenner discovers that injecting people with pus from cowpox—a much less dangerous ailment than smallpox—can protect them from contracting the latter disease. His medical breakthrough, vaccination, gets its name from a Latin word for cow, vacca. As it becomes widely used and sometimes mandated by law, it spawns the first anti-vaccination movement, driven—like later anti-vax sentiment—by factors such as skepticism toward medical science, and the belief that forced vaccination is a violation of personal liberty.

1866: Anti-vaxxers assemble

After giving vaccination to the world, Great Britain becomes the first center of organized anti-vaccination activity. The Anti-Compulsory Vaccination League—which later evolved into the National Anti-Vaccination League—is founded in 1866. At an 1875 meeting, it passes a motion summarizing its general outlook: “That in the judgment of this meeting vaccination is an unprincipled, unscientific, useless, and pernicious practice; that the law which [enforces] the practice is a violation of political science, and an offence against the free constitution of England, and that this meeting therefore pledges itself to use every legitimate means to free the country from this unwise and despotic law.”

Following Britain’s lead, vaccine skeptics in the U.S. start organizations such as the Anti-Vaccination Society of America (1879), the New England Anti-Compulsory Vaccination League (1882), and the Anti-Vaccination League of New York City (1885). Their crusade leads to the end of mandatory vaccination laws in several states.

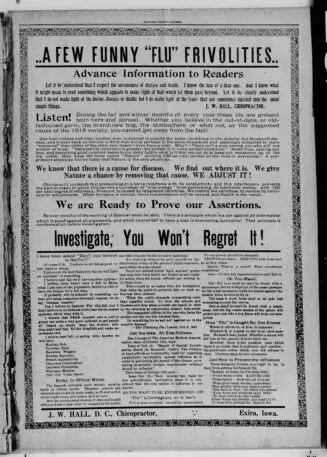

1918: No Spanish flu vaccine, but vaccine anxiety

The so-called Spanish flu spreads around the world, infecting half a billion people and killing somewhere between 17 and 100 million, according to various estimates. Not surprisingly, scientists attempt to create a vaccine to combat it. They are unsuccessful. But even the idea of testing prototype vaccines raises the hackles of the vaccine-averse. “DO YOU WANT TO BE EXPERIMENTED ON?” bellows an Iowa chiropractor in a full-page newspaper ad that raises anti-vax fears as part of a sales pitch for his services.

1954: Winchell prompts a panic

As Dr. Jonas Salk’s groundbreaking polio vaccine is about to go into nationwide trials involving 1.8 million schoolchildren, influential columnist and broadcaster Walter Winchell attacks the vaccine on his radio show, saying that it “may be a killer” based on monkeys having died during testing. His prominence makes the assertion front-page news; an estimated 150,000 parents rescind permission for their children to participate in the trials. Public health officials, newspaper editorialists, and Salk himself swiftly push back on Winchell’s charges.

Winchell does little to backpedal, likening the vaccine to phony cancer “cures” he has derided and saying that even 99% odds of safety are inadequate. Nonetheless, the trials go on, the vaccine is approved for production, and polio’s days as a scourge of everyday life are numbered.

1955: An actual vaccine health crisis

After Salk’s vaccine is approved, six pharmaceutical companies gain the right to produce it. One, Berkeley, California-based Cutter Laboratories, accidentally releases 120,000 doses of vaccine containing live virus. Rather than curtailing polio, these doses spread it, leading to localized epidemics that ultimately kill 10 people and paralyze another 200, mostly children. The so-called “Cutter incident” leads to the U.S. surgeon general calling for a temporary halt to the vaccination program, and to a drop in vaccinations thereafter. But public confidence rebuilds, and dramatic advances are made in controlling polio by 1960.

1972: The Tuskegee experiment’s damage lingers

In a bombshell exposé, AP reporter Jean Heller reveals a horrifying government research project in which Black male residents of Tuskegee, Alabama, who had syphilis were denied knowledge of that diagnosis so the illness’s effects could be studied. Over the study’s 40-year history, 128 of its subjects died of syphilis or related complications, 40 of their wives contracted the disease, and 19 children were born with it. Among the scandal’s festering aftereffects: It’s taken as supporting evidence for conspiracy theories such as the idea that the U.S. government intentionally spread AIDS in Black communities.

Today, some experts argue that the Tuskegee experiment is too often used as a facile overarching explanation for Black Americans’ skepticism over government health initiatives such as vaccination. (Besides, as a group, they’re not uniquely cautious about COVID-19 vaccination.)

1979: A new law addresses vaccination fears

In the 1970s, members of a British advocacy group called the Association of Parents of Vaccine Damaged Children say that their children suffered disastrous health consequences such as brain damage after being vaccinated for various diseases. Their claims gain some support in the medical community, and publicity over the matter seems to lead to a downturn in parents’ willingness to have their children vaccinated for pertussis, better known as whooping cough.

The U.K. government initially resists calls to compensate the parents who claim vaccine-related harm to their children. But a belief that recompense might turn around the vaccination rate eventually leads to legislation called the Vaccine Damage Payments Act of 1979. The law arrives too late to increase vaccination rates in time to stop a major pertussis epidemic in 1978 and 1979, but it remains in effect today.

1998: The Lancet spreads misinformation

British medical journal The Lancet publishes a study asserting that the widely used measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine might be linked to the steep increase in children diagnosed with autism. Its lead author, Andrew Wakefield, calls for its use to be suspended. Wakefield’s research eventually collapses under the weight of investigative reporting that reveals falsification and conflicts of interest. The Lancet retracts the study in 2004, and Wakefield is removed from the British medical register in 2010. But the fears he stoked among parents live on and are amplified by others.

2005: RFK Jr. links vaccines and autism

Activist and Kennedy scion Robert F. Kennedy Jr. writes “Deadly Immunity,” an article that’s published by both Rolling Stone and Salon. The piece claims that a sprawling conspiracy conceals the alleged fact that thimerosal, a mercury-based preservative once used in childhood vaccines, explains the dramatic increase in autism diagnoses. Salon soon appends multiple corrections, and it retracts the article altogether in 2011. Kennedy blames most of the errors on his editors. Meanwhile, an increasing number of children continue to be diagnosed with autism even though thimerosal was removed from nearly all childhood vaccines in 2001.

2007: Jenny McCarthy ignites a celebrity crusade

On The Oprah Winfrey Show, actress, model, and TV personality Jenny McCarthy discusses her new book about her son’s autism, which she says she believes was caused by the MMR vaccine. She continues to make the assertion on other programs such as Larry King Live and The Ellen DeGeneres Show, greatly raising the profile of Andrew Wakefield’s discredited theories, usually with little pushback from the shows’ hosts.

2015: Twitter becomes a “vaccine choice” nexus

After a measles outbreak at Disneyland, California legislators propose a law to prohibit parents from using personal belief as a way to opt out of vaccination requirements for schools and daycare centers. On Twitter, a drumbeat of opposition to the bill targets lawmakers, lobbyists, and doctors. Internet researchers Renee DiResta and Gilad Lotan write up their analysis of such tweets, showing them to be part of a coordinated attack—often including outright harassment—by groups attempting to rebrand their movement from “anti-vax” to “pro-SAFE vaccine.” (The law passes anyway.)

2016: Wakefield turns documentarian

Disgraced British doctor Andrew Wakefield directs a documentary film, Vaxxed: From Cover-Up to Catastrophe. Picking up on his 1998’s study’s themes, it charges that a conspiracy has suppressed evidence of a link between the MMR vaccine and autism. Bad Astronomy’s Phil Plait calls the film’s central theory “baloney” and “on the level of the Apollo moon hoax.”

Vaxxed is initially welcomed into the Tribeca Film Festival and defended by festival cofounder Robert De Niro; amid the resulting controversy, he has second thoughts and withdraws the invitation. In 2019, the film inspires a sequel, Vaxxed II: The People’s Truth, with Robert F. Kennedy Jr. as executive producer.

2019: Pinterest cracks down on anti-vaxxers

While social media giants such as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube continue to take a laissez-faire approach toward anti-vaccine misinformation, Ifeoma Ozoma, a public policy and social impact manager at Pinterest, spearheads the company’s initiative to take a radically different direction. Pinterest aggressively combats anti-vaccine content by blocking searches for related terms and deleting pins with memes such as “Proud to be anti-vax, that means I’m not just smarter than you but also more likely to stay that way.” (Ozoma later resigns, alleging that she faced ongoing racism and misogyny at the company.)

2019: Measles is back

Vaccination against measles begins in the U.S. in 1963 and proves so successful that the World Health Organization declares the disease eliminated in the country in 2000. But 19 years later, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports 1,282 cases of measles in the U.S., the most since 1992. Worldwide, cases hit a 23-year high. Experts such as Dr. Anthony Fauci of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases blame the alarming numbers on decreased herd immunity in areas where many people go unvaccinated, and they hold the anti-vaccination movement directly responsible for the disease’s return.

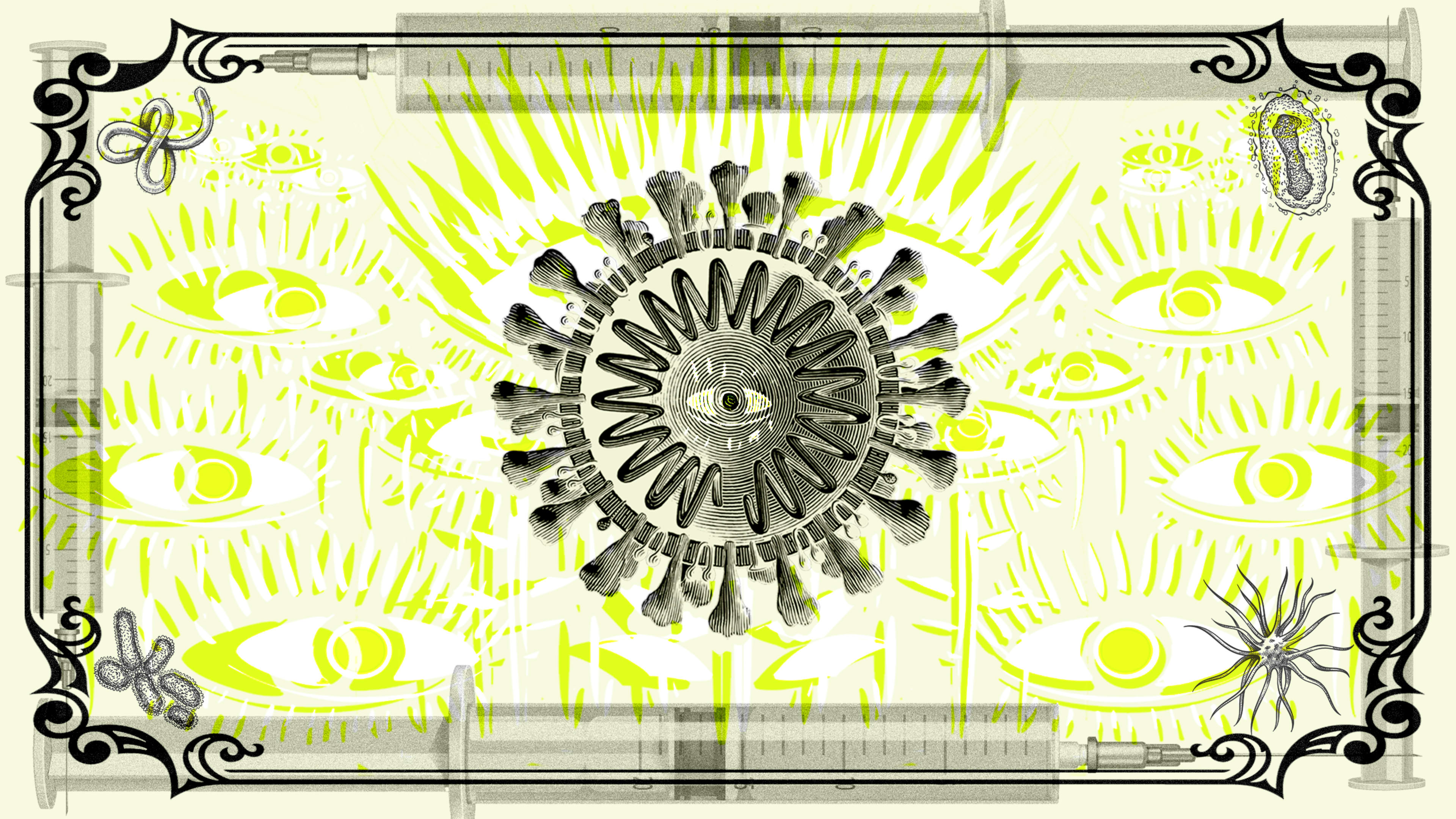

2020: COVID-19, Bill Gates, and 5G, oh my

With COVID-19 vaccines on their way, conspiracy theorists begin to fold anti-vax elements into complex hoaxes that also incorporate other favorite topics of disinformation such as philanthropist and Microsoft cofounder Bill Gates, electronic tracking, and 5G technology. As NPR’s Monika Evstatieva reports, one such twisty and wildly false theory explains that the COVID-19 pandemic was spread intentionally so that Gates and other members of the global elite could use vaccinations as a ruse to implant people with chips that can be used to spy on them via 5G.

2021: RFK Jr. gets booted off Instagram

As social networks begin taking vaccine misinformation more seriously, Facebook bars Robert F. Kennedy Jr. from Instagram for “sharing debunked claims about the coronavirus or vaccines.” However, Kennedy’s accounts on Facebook itself and Twitter, which include posts expressing concern about alleged negative effects of COVID-19 vaccines, remain online.

Like the social giants’ steps against other types of misinformation, their recent moves against anti-vax content are far from comprehensive. And the problem was allowed to build for so long that it has a momentum that’s difficult to stop through belated policy adjustments. It would be nice to think we’ll make inroads into this threat to public health—but history is full of sobering evidence that it’s not going to simply fade away.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the final deadline, June 7.

Sign up for Brands That Matter notifications here.