How do you pull people out of the rabbit holes that lead to violent extremism, or keep them from falling in? If conspiracy-laced hate is another kind of pandemic pushed by online superspreaders, could we build something like a cure or a vaccine?

The deadly Capitol riot on January 6 has set off a fresh scramble to answer these questions, and prompted experts like Vidhya Ramalingam to look for new ways to reach extremists—like search ads for mindfulness.

“It’s so counterintuitive, you would just think that those audiences would be turned off by that messaging,” says Ramalingam, cofounder and CEO of Moonshot CVE, a digital counter-extremism company that counts governments like the U.S. and Canada and groups like the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) and Life After Hate among its clients. But Moonshot’s researchers recently found that Americans searching for information about armed groups online were more likely than typical audiences to click on messages that encourage calmness and mindful thinking.

“Our team tried it, and it seems to be working,” Ramalingam says. The finding echoes previous evidence suggesting that some violent extremists tend to be more receptive to messages offering mental health support. “And that’s an opening to a conversation with them.”

The risk of violence is buoyed by a rising tide of conspiracy theories and extremist interest, which Ramalingam says has reached levels comparable to other “high risk” countries like Brazil, Sri Lanka, India, and Myanmar. In terms of indicators of extremism in the U.S., “the numbers are skyrocketing.”

How to reach people—and redirect them

To get those numbers, Moonshot goes to where the toxicity tends to spread, and where violent far-right groups do much of their recruiting: Twitter, YouTube, Instagram, and Facebook, but also niche platforms like MyMilitia, Zello, and Gab. But core to its strategy is the place where many of us start seeking answers—the most trafficked website of all. “We all live our lives by search engines,” Ramalingam says.

Vidhya RamalingamWe turn to Google and ask the things that we won’t ask our family members or partners or our brothers or sisters.”

Search can also convey to users an illusory sense of objectivity and authority in a way that social media doesn’t. “It’s important that we keep our eye on search engines as much, if not more than we do social media,” Safiya Noble, associate professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, and cofounder and codirector of the UCLA Center for Critical Internet Inquiry, recently wrote on Twitter. “The subjective nature of social media is much more obvious. With search, people truly believe they are experiencing credible, vetted information. Google is an ad platform, the end.”

Moonshot began in 2015 with a simple, insurgent strategy: Use Google’s ad platform—and the personal data it collects—to redirect people away from extremist movements and toward more constructive content. The idea, called the Redirect Method, was developed in partnership with Google, and widely touted as a way to reach people searching for jihadist content, targeting young men who were just getting into ISIS propaganda, or more radicalized people who might be Googling for information on how to sneak across the border into Syria. The idea is to steer potential extremists away—known as counterradicalization—or to help people who are deep down a rabbit hole find their way out through deradicalization. That might mean connecting them with a mentor or counselor, possibly a former extremist.

What began with a focus on jihadism and European white supremacy is now part of an effort to track a nexus of extremism, conspiracy theories, and disinformation—from QAnon to child exploitation content—from Canada to Sri Lanka. But for Moonshot, the U.S. is a new priority. Last month, Ramalingam, who grew up in the states, returned to open the company’s second office in D.C., where it can be closer to policy makers and practitioners. The company is also dropping the acronym from its birth name, Moonshot CVE: “Countering violent extremism” has become nearly synonymous with a misguided overemphasis on Muslim communities, Ramalingam points out, and in any case, old tactics aren’t sufficient. As extremist ideas have stretched into the mainstream, Moonshot’s once tiny target audiences now number in the millions.

“We can’t rely on what we knew worked when we were dealing with the dozens and the tens of people that were really on the fringes,” she says. “We need to be testing all sorts of new messaging.”

Understanding the data

If you were among the thousands of Americans who Googled for certain extremist-related keywords in the months around the election—phrases like “Join Oath Keepers Militia,” “I want to shoot Ron Wyden,” and “How to make C4″—you may have been targeted by the Redirect Method. It could have been a vague, nonjudgmental message at the top of your search results, like “Don’t do something you’ll regret.” Click, and you could end up at a playlist of YouTube videos with violence-prevention content, like a TED Talk by a would-be school shooter or testimonies from former neo-Nazis. Or you might encounter videos promoting calmness, or a page directing you to mental health resources. Around January 6 alone, Ramalingam says more than 270,000 Americans clicked on Moonshot’s crisis-counseling ads.

To do this, Google has given Moonshot special permission to target ads against extremist keywords that are typically banned. But while Moonshot launched the Redirect Method with Google’s help, these days it typically pays the ad giant to run its campaigns, just like any other advertiser. And now, given the sheer scale of the audiences Moonshot is reaching in the U.S., “the costs are off the charts,” Ramalingam says. Regarding its recent ADL-backed campaign, she says, “We’ve never paid this much for advertising in any one country on a monthly basis.”

This ad data comes with caveats. When looking at extremist search terms, for instance, Moonshot can’t be certain it’s measuring individual people or the same person searching multiple times. It also can’t know if it’s targeting an extremist or a journalist who’s simply writing about extremism.

“At a time when people have been locked in their homes and consuming disinformation, with record levels of domestic violence, anxiety, depression, substance abuse, what’s the antidote? People have bought guns and ammunition in record numbers. So they’re anxious, they’re angry, isolated, and they’re well-armed,” he says. “It’s a perfect storm.”

Colin ClarkeThey’re anxious, they’re angry, isolated, and they’re well-armed. It’s a perfect storm.”

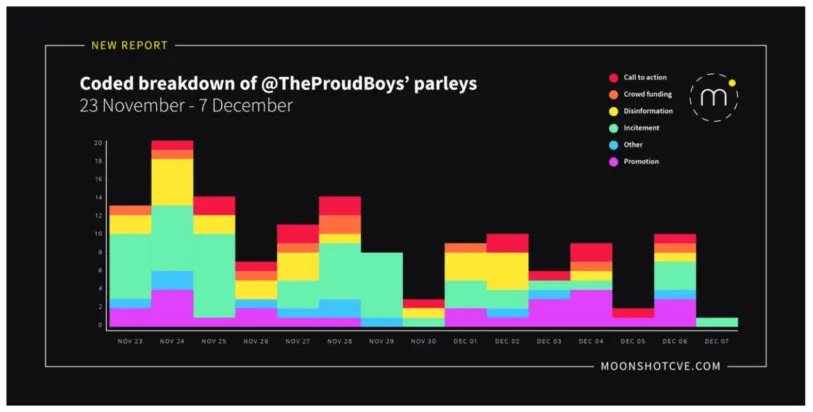

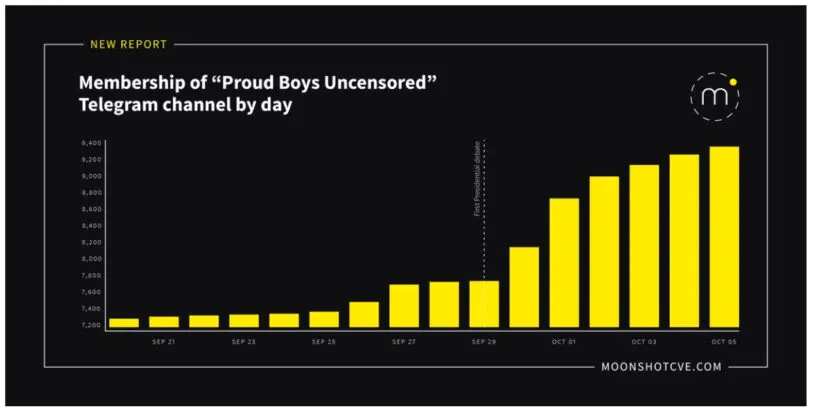

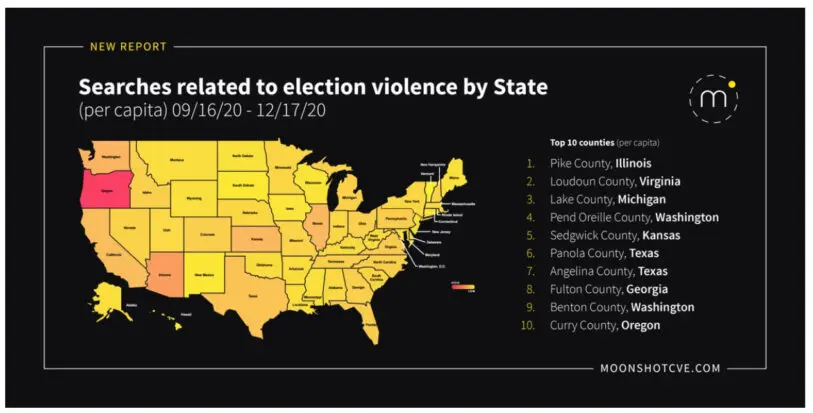

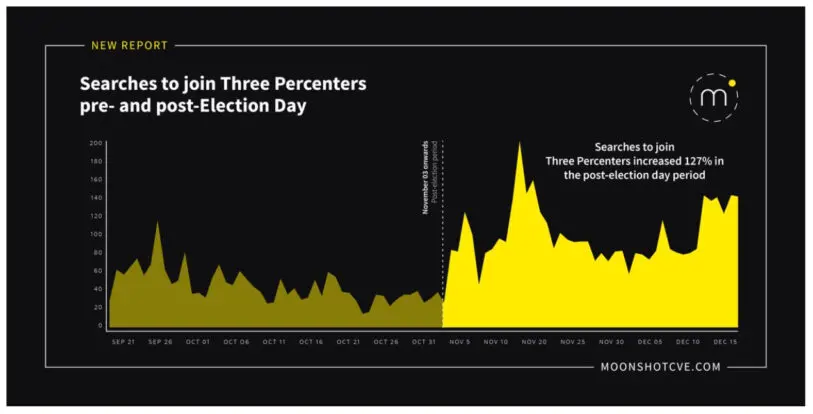

In a recent analysis, done in partnership with the ADL and gathered in a report titled “From Shitposting to Sedition,” Moonshot tracked tens of thousands of extremist Google searches by Americans across all 50 states during the three months around Election Day. It saw searches spike around big political events, but also along geographic and political lines. In states where pandemic stay-at-home orders lasted 9 or fewer days, white-supremacist-related searches grew by only 1%; in states where stay-at-home orders were 10 days or longer, the increase was 21%.

The politics of the pandemic fomented domestic extremist interest, but also helped unite disparate fringe movements, from militias to climate denialists to anti-maskers and anti-vaxxers. “We started to see this worrying blending and metastasization of all these different ideologies in the U.S.—far-right groups blending and reaching across the aisle to work with anti-vax movements,” Ramalingam says. And it’s during times of crisis, she notes, “when we see these actors just grasping to turn fear and anxiety in society into an opportunity for them to grow.”

But Ramalingam isn’t just concerned about the most hard-core armed believers. After the election and the events of January 6, she worries now about splintered far-right groups and disaffected conspiracy theorists who are grappling for meaning. That puts them at risk of further radicalization, or worse.

“There are a lot of people who basically just feel misled, who feel like they’ve lost a lot because they followed these conspiracy theories,” she says. QAnon channels filled up with anxiety, self-harm, and talk of suicide, “like a father saying, ‘My son won’t speak to me,’ people who have lost their jobs, people who said, ‘I lost my family because of this,’ ” Ramalingam says. “And so there’s a real moment now where we need to be thinking about the mental health needs of people who, at scale, bought into these conspiracy theories and lies.”

What to say

To reach violent radicals or conspiracy theorists to begin with, Ramalingam urges caution with ideological arguments. Shaming, ridiculing, and fact-based arguing can prove counterproductive. In some cases, it can be more effective to use nonjudgmental and nonideological messages that don’t directly threaten people’s beliefs or tastes but that try to meet them where they are. For instance, as Frenett suggests, if someone is searching for Nazi death metal, don’t show them a lecture; instead, show them a video with a death metal score, but without the racism.

Simple reminders to be mindful, and to think about how one’s actions impact others, may help. In its recent campaign, some of Moonshot’s most effective messaging asked people to “reflect and think on their neighbors, their loved ones, the people in their immediate community around them, and just to reflect on how their actions might be harmful to their loved ones,” Ramalingam says.

People interested in armed groups were most receptive to messages of “calm” offering mindfulness exercises. For all audiences, Moonshot found particularly high traction with an ad that said, “Anger and grief can be isolating.” When people clicked through, to meditation content or mental health resources, Ramalingam notes that “they seem to be watching it, or listening to it, or engaging with it for a long time.”

To reach QAnon supporters, Moonshot found the most success with messages that seek to empathize with their need for psychological and social support. “Are you feeling angry? Learn how to escape the anger and move forward,” said one Moonshot ad directed at QAnon keywords, which saw a click-through rate around 6%, twice that of other types of redirect messages. Clicking on that took some users to r/Qult_Headquarters, a subreddit that includes posts by former adherents.

Preventing the spread of violent extremist ideas involves a broader set of strategies. To bolster trust and a shared reality among the general public—people who haven’t yet gone down the rabbit hole—researchers are exploring other countermeasures like “attitudinal inoculation,” alerting people to emerging conspiracy theories and warning of extremists groups’ attempts at manipulation.

Experts also urge enhancing public media literacy through education and fact-checking systems. Governments may not be trusted messengers themselves, but they could help in other ways, through a public health model for countering violent extremism. That could mean funding for local community activities that can keep people engaged, and for mental health and social programs, an idea that then-Vice President Joe Biden endorsed at a 2015 White House summit on countering violent extremism.

Vidhya RamalingamRhetoric that’s shaming of those ideologies can be really important and powerful from people in positions of power.”

Speaking of the White House, Ramalingam emphasizes that extremist ideologies warrant stern condemnation from public figures. Companies should deplatform the superspreaders of racism and disinformation, and political, cultural, and religious leaders should vehemently denounce them.

“Rhetoric that’s shaming of those ideologies can be really important and powerful from people in positions of power,” Ramalingam says. That’s for an already skeptical audience “that needs to hear it reinforced, but also the audience that is in the middle and doesn’t really know or doesn’t care that much. And that audience really needs to hear, ‘This is not okay. This is not acceptable. This is not a social norm.’ ”

But when addressing more extremist-minded individuals, Ramalingam suggests a gentler approach. “If someone is coming at you with an attack, you kind of pull yourself back into a corner and stand your ground and defend it,” she says. “And so if that’s our approach with the most extreme of society, that will actually worsen the problem.”

Does this work?

In the face of the domestic terror threat, mindfulness and compassion might sound like entering a space-laser fight with a water pistol or a hug.

But to Brad Galloway, who helps people exit right-wing extremist groups, Moonshot’s messaging makes sense. In a previous life, he used chat rooms and message boards to recruit people into a neo-Nazi group. After he joined—drawn in largely by camaraderie and music—what had been a U.S.-only organization eventually grew to 12 countries, thanks largely to the internet. Now Galloway is a coordinator at the Center on Hate, Bias and Extremism at Ontario Tech University, where he often urges his mentees to be more mindful, especially online.

“I ask people to think, Do I really need to watch this video of a school shooting?” Instead he encourages “positive content” to displace the stuff that can accelerate or even provoke radicalization.

Galloway, who has worked with Moonshot, Life After Hate, the Organization for the Prevention of Violence, and other groups, says the same principle of positive content applies to real life, too: Connecting with old friends and finding fun new activities can help people leave corrosive extremist communities. “What’s positive to that user, and how do we make that more prominent to them?”

A 2018 Rand Corp. report on digital deradicalization tactics found that extremist audiences targeted with Redirect “clicked on these ads at a rate on par with industry standards.” Still, they couldn’t say what eventual impact it had on their behavior. As new funding flows in, and as experts throw up an arsenal of counter-radicalization ideas, there’s still scant evidence of what works.

For its part, Moonshot says its data suggests that some of its target audiences have viewed less extremist content, and points to the thousands of people it has connected to exit counseling and mental health resources. Still, Ramalingam says that the company sees “greater potential for us to assess whether our digital campaigns can lead to longer-term engagement with users, and longer-term change.”

The missteps of previous digital wars on terror haunt Moonshot’s work.

There are other serious concerns as well. The missteps of previous digital wars on terror haunt Moonshot’s work: secret and extralegal surveillance systems, big data political warfare by military counter-radicalization contractors-turned-conspiracy mongers, untold violations of privacy and other civil rights. If Moonshot is tracking what messaging influences who, what data does it collect about “at risk” users, and where does that end up, and why? And who is at risk to begin with?

Ramalingam worries about the privacy concerns; she acknowledges that thanks to ad platforms and brokers, Moonshot can tap into “actually a heck of a lot of data.” But, she stresses, Moonshot isn’t accessing people’s private messages, and its work is bound by the stricter European personal data protections of the GDPR, as well as by an ethics panel that helps evaluate impacts. In any case, she argues, Moonshot is simply taking advantage of the multibillion-dollar digital platforms that drive most of the internet, not to mention the markets.

“As long as Nike and Coca-Cola are able to use personal data to understand how best to sell us Coke and sneakers, I’m quite comfortable using personal data to make sure that I can try and convince people not to do violent things,” Ramalingam says. Should that system of influence exist at all? “I’m totally up for that debate,” she says. “But while we’re in a context where that’s happening, I think it’s perfectly reasonable for us to use that sort of data for public safety purposes.”

What about the platforms?

The tech giants have run their own redirect and counter-speech programs as part of ongoing efforts to stem the toxicity that flourishes on their platforms. Google touts its work with Moonshot battling ISIS, its research on extremism, and its efforts to remove objectionable content and reduce recommendations to “borderline” content on YouTube. In December, its rights group Jigsaw published its findings on the digital spread of violent white supremacy.

Facebook tested the Redirect Method in a 2019 pilot in Australia aimed at nudging extremist users toward educational resources and off-platform support, a system that echoes its suicide-prevention efforts, which use pop-ups to redirect at-risk users to prevention hotlines. In an evaluation commissioned by Facebook last year, Moonshot called the program “broadly successful,” and recommended changes for future iterations. Facebook has also tested the program in Indonesia and Germany.

Ramalingam praises the tech platforms for their efforts, and supports their decisions to deplatform vast numbers of far-right and QAnon-related accounts, even if that’s made researching online extremism harder. Still, she says, Big Tech is doing “not nearly enough.”

Extremist content continues to slip through the platforms’ moderation filters, and then gets rewarded by the algorithms. Facebook’s own researchers have repeatedly shown how its growth-focused algorithms favor extremist content. Despite YouTube’s moderation efforts, political scientist Brendan Nyhan recently reported, the site’s design can still “reinforce exposure patterns” among extremist-curious people.

“The tech companies have an obligation to use their great privilege . . . of being a conduit of information, to get information and helpful resources to people that might be trapped in violent movements,” Ramalingam says.

As companies and lawmakers and law enforcement scramble for solutions in the wake of the events of January 6, Ramalingam also cautions against rash decisions and short-term thinking. “There’s an imperative to act now, and I have seen in the past mistakes get made by governments and by the tech companies just delivering on knee-jerk responses,” she says. “And then once the conversation dies down, they go back to essentially the way things were.”

Emotional reactions are understandable, given the shock of January 6, or of a family member who’s fallen down a rabbit hole, but they tend to be counterproductive. What works for battling violent extremism on a personal, one-on-one level, Ramalingam says, can also help fight it on a national scale: Avoid assumptions, be mindful, and consider the actual evidence.

“The way counselors and social workers do their work is they start by asking questions, by trying to understand,” she says. “It’s about asking questions so those people can reflect on themselves.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.