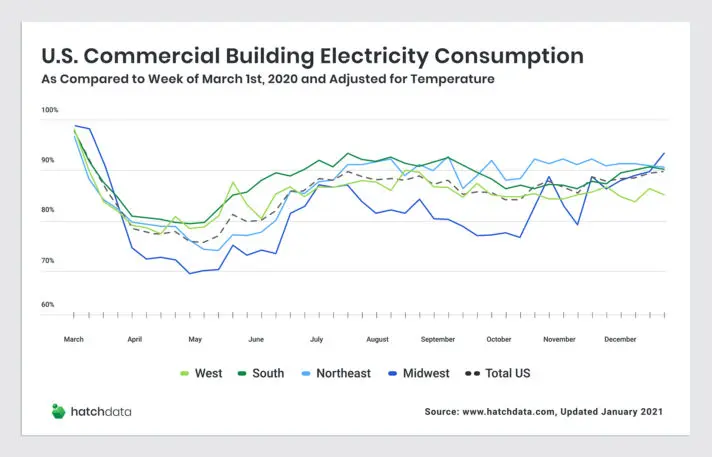

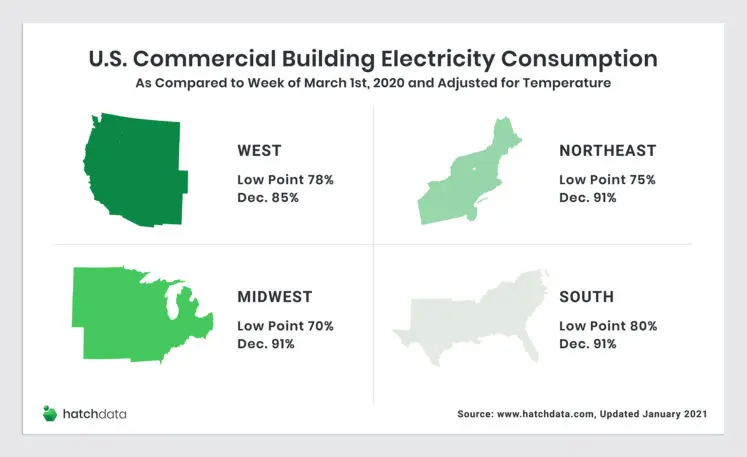

In May, when the pandemic was solidly in what would be its first peak in cities around the United States, office electricity consumption dropped by nearly 25%—a predictable dip as many companies closed their doors and turned off the lights. Energy-sucking office equipment and lighting systems were switched either off or to standby mode as workers left the buildings, and office electricity use came down to record lows. That’s according to Hatch Data, which tracks and analyzes building data from utility meters and equipment in more than 550 million square feet of occupied space in about 2,700 commercial properties across North America.

Even though many of these offices remain closed or nearly emptied of people, electricity use is climbing steadily back up to pre-pandemic levels. By the fall, electricity consumption had climbed back up to 90% of what it was before the lockdowns and office closures, and it has stayed there, according to Hatch Data. Offices are still empty, but they’re using almost as much energy as they were when they were full.

One surprising reason electricity use is normalizing in empty offices is that, for many buildings, energy-wasting practices are legal obligations within their leases. “It’s common for leases to stipulate hours of service delivery, and that service delivery can be as detailed as we will deliver 70-degree Fahrenheit air to your space between these hours,” says Zach Robin, CEO of Hatch Data.

Owners and operators don’t have the legal right to ignore those contractual agreements, which means the air conditioner keeps running. The language of these leases varies from building to building, but unless tenants explicitly consent to changes—say, during an unanticipated and indefinite closure of business premises during a global pandemic—the building operations remain as agreed, and the electricity keeps flowing as scheduled.

Air conditioners aren’t the only reason electricity use is still close to its pre-pandemic levels. Many building systems, such as water heaters and server rooms, are designed to operate all the time, not to be turned on and off like a light switch in the office kitchen. To ensure long-term functionality, many operational systems continue working even when people aren’t in the building. For owners, this is one of the costs of operating buildings. “The last thing they want to do is shut everything off and then have an issue with mechanical degradation or mold,” Robin says. “You can’t just mothball a building.”

But keeping a boiler boiling or emergency exit lights illuminated is different from air conditioning dozens of floors of empty offices to maintain a temperate 70 degrees all day long. Robin says that the only way that contractually set electricity practices can adapt to an unusual circumstance such as this pandemic is for tenants and owner-operators to be in contact and agree to make adjustments. This, he says, is already happening, especially in bigger buildings and among larger tenants.

Buildings that implemented new system settings based on lower occupancy saw electricity usage drop significantly during their empty period, going down to just 60% of their typical need, according to Hatch Data. Robin says many big building owners and operators were able to make these kinds of adjustments very early on, which helped contribute to the record low electricity use back in May. If other buildings were to follow this model of more precisely tracking when and where electricity is actually needed, he says energy use in office buildings could see long-term reductions, even as they return to pre-pandemic levels of occupancy.

Being able to make these changes will require more communication between tenants and owners, and also more data about how spaces are being used as the pandemic drags on. Robin says that if the two or three different tenants on one floor of a 50-story office building install better sensors to determine when rooms are being used and how much cooling they need, building-wide systems such as air handlers can be adjusted to more precisely meet those needs. This kind of detail will be important as offices begin to reopen, Robin says.

“There are both technologies and processes that are available to help [building owners and tenants] capture the value there,” he says. “If you’re a tenant in one of these spaces, engaging your ownership or operating partner in conversations about how they can help is really the path forward.”

Electricity use is likely to keep climbing, though. Buildings are already implementing new standards for ventilation, higher-rated air filtration, and increased cleaning protocols, Robin says, and all these require more electricity, either directly or indirectly. These building systems will be working even harder to try to make the office a safe place to be—and sucking even more electricity along the way.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.