We all have witnessed Donald Trump’s callous disregard for the health of the American people during COVID-19. That extends to his own staff. He discredited his own coronavirus advisor Anthony Fauci, his cabinet has refused to wear masks at the White House, and there have been multiple White House outbreaks over the past year. More than 130 individuals serving across his Secret Service detail have fallen ill, not to mention the president himself.

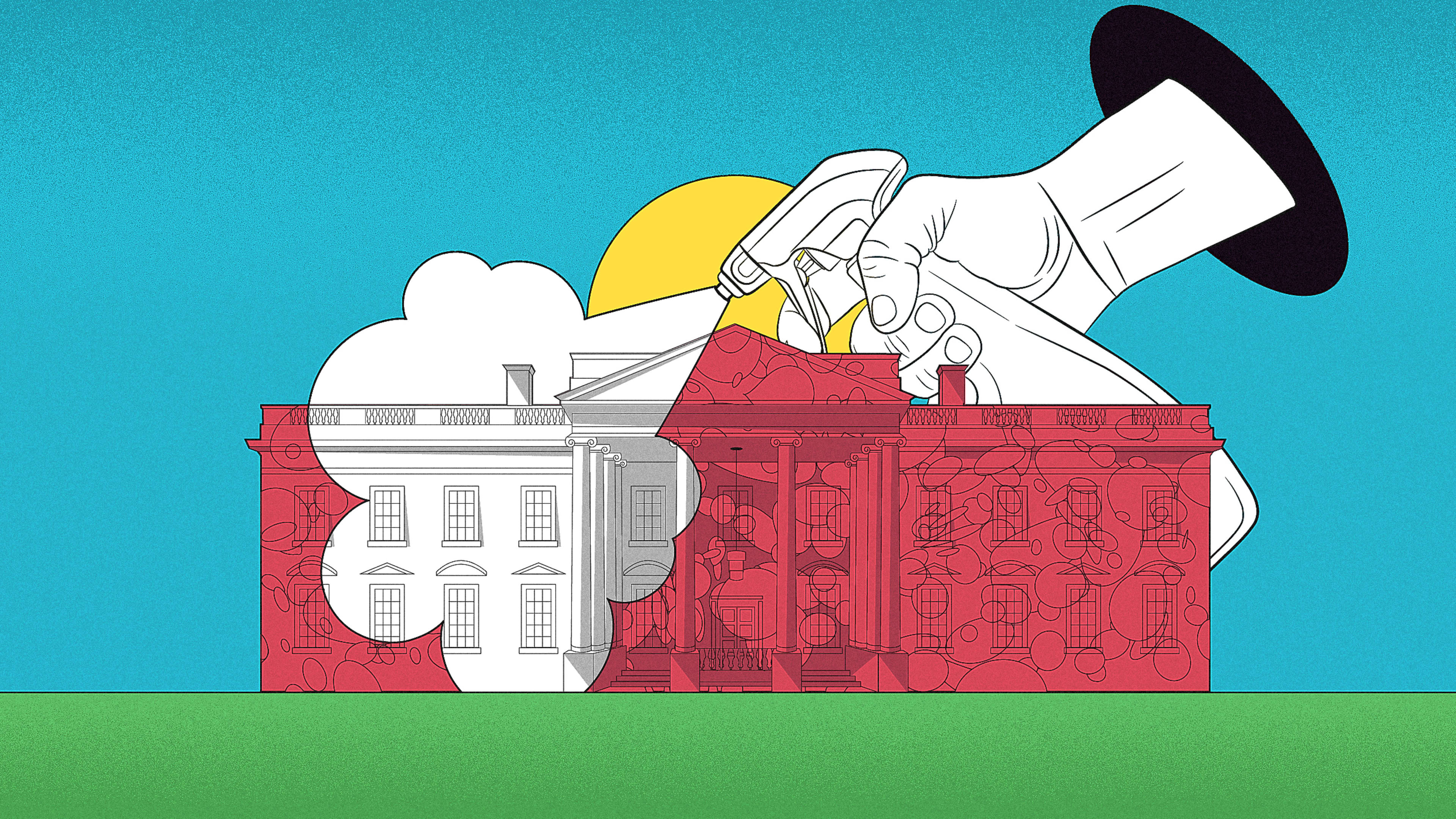

As Joe Biden prepares to take office this week, he has ordered nearly $500,000 in cleaning services on top of the normal transitional work done by White House staff. We were curious: What steps could his staff take to scrub the White House clean of COVID-19 and ensure that the 55,000 square foot historic building isn’t a pandemic Petri dish? We reached out to five experts in infectious environments to find out what they think.

The core challenge

An important thing to know about sterilizing any domestic space is that you can do damage by using cleaners that are too harsh. This goes double for the President’s home, which is full of historic artifacts.

“The White House is a very different house than my house or your house. So when you’re thinking about how to clean a hospital environment versus a home versus a historical building—and the White House you can think of almost like a museum in many ways—you need to use very different methods,” says Andrea Armani, the Ray Irani Chair in Engineering and Materials Science and Professor of Chemical Engineering and Materials Science at the USC. “In a hospital, you can use bleach on almost every surface. It’s designed to be sterilized. There aren’t very nice pieces of art hanging on the wall. Whereas you move into a home environment, I have wood floods—I don’t plan on cleaning my wood floors with bleach. Most people have hanging draperies. You can’t just splash those with bleach or everything is white.” In the White House, one wrong move, and you could be destroying a piece of American history.

Cleaning and replacing the soft stuff

The first step Armani suggests is to begin with all the soft-touch items.

“Step one is look around the White House, and everything that’s a linen, strip that off and clean it. You can do the same thing with the carpets. You can take those, roll ’em up, and clean those,” says Armani. This goes for drapes and couch covers, too.

“Going with something like a thermal tool would be best, because you aren’t going to damage the fabric,” says Armani. “That’s basically how they clean linens in hospitals. They take the sheets, put them in a high temperature oven, and clean them with steam.”

Sterilizing hard surfaces . . . and nooks and crannies

With the soft items out of the way, it’s time to consider the hard surfaces, like wood furniture. How do you sterilize it?

Before unpacking that problem further, it’s worth bringing up an important point: General scientific consensus is that COVID-19 is airborne in its transmission. If we think that it’s both large and small particles in the air making us sick, does sterilizing surfaces actually matter in this case? Andrew Streifel University, a Hospital Environment Specialist who helped pioneer the design of negative pressure rooms, was originally skeptical that COVID-19 was airborne. Now he believes it is. But he still recommended that Biden’s White House use surface sterilization.

To clean White House surfaces, at first Streifel suggested the cleaning staff might use vaporized hydrogen peroxide, fogging the room with disinfectant to top every surface with COVID-killing chemical. Technically, that would work pretty well—as it does in hospitals—but it would be devastatingly harsh on antiques.

“[With something like] the Lincoln Desk, you can’t just clean that with hydrogen peroxide,” says Armani, in reference to Abraham Lincoln’s desk, still found in his room on the second floor of the White House. “The hardest to clean surfaces are wood surfaces. You can’t take a desk and put that in a washing machine.”

In this case, both Streifel and Armani agree the most delicate solution would be UVC-light, and perhaps using wands to manually shine light onto the furniture.

“It’s going to be a very slow process…and you have to worry about the person cleaning that surface,” says Armani, alluding to the burns that UVC can inflict on human skin, while also urging a cleaning staff to make sure they get into the nooks and crannies of hard furniture. “It’s very manually intensive, but if you have a delicate surface, it’s your only option.”

Addressing the air

Okay, so all of the White House’s surfaces are clean. Now we have to mull the White House’s air, where COVID-19 droplets could be floating. Luckily, air is the easiest thing to clean. There are all sorts of ways the Biden administration could do it.

Martin Bazant, MIT professor of mathematics, who built an interactive model that predicts the infectiousness of COVID-19 in different environments, suggests “running strong ventilation, ideally with HEPA air filtration, and opening windows with fans for a few hours before resuming normal occupancy without masks,” he says. In other words, strategic use of windows, fans, and HEPA filters could clear the White House air in less than a day. David Edwards, Harvard bioengineering researcher and entrepreneur, adds that, “There will be dead zones where air does not circulate well—desks, seats, couches, bathrooms,” he says. These places should be identified and addressed by circulating and filtering the air. (A portable HEPA filter could handle that.)

But it doesn’t even have to be that hard. Assuming the White House could go unoccupied, experts concur that diseased air would likely just rectify itself. “You can reduce transmission in the air by waiting 24 to 48 hours [before entering the room],” says Armani, over which time the virus should simply fall to the ground (pointing out that if this method of air cleaning were used, it should happen before surface cleaning, not after). “That I don’t view as cleaning, so much as what you’d do if you were airing out a building.”

Then moving forward, assuming the White House hasn’t done this already, staff could invest in upgrading the central HVAC system with powerful fans, suggests Qingyan Chen, professor of mechanical engineering at Purdue who is an expert on particulate air flow. That would allow the White House to upgrade from normal air filters, which trap dust, to high-grade HEPA filters, which can trap viruses.

Considering staff

The last, and trickiest challenge for the Biden Administration’s sterilization efforts, has nothing to do with furniture, fixtures, or oxygen. It’s the challenge of personnel. The White House has 5,900 people on staff as of last count. Some of those people are in-house cooks, others might handle communications outside the Oval Office, others might oversee Camp David. These individuals don’t all literally work inside the White House, but they are considered key support personnel of the President. And those who work in the White House are actually at risk of carrying and transmitting COVID-19.

The challenge goes beyond mere mask-wearing. It’s a challenge of staff management and carefully coordinated quarantining, which would have needed to have started weeks ago. Especially given the heightened security details in D.C. following the insurrection at the Capitol, it seems unlikely that White House staff will be able to social distance from thousands of additional troops, just as a more virulent strain is taking over the U.S. The good news, at least, is that Joe Biden has already received his second vaccination shot, and Kamala Harris has received her first.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.