On the afternoon of January 6, as a giant crowd began to swarm the U.S. Capitol, Jason Moore, a 36-year-old digital strategist, was at home in Portland, Oregon, switching between CNN and MSNBC. “I try not to get caught up in the sensationalism of cable news,” he says, but admits he had to watch. Soon, concern became shock. “I could not believe what I was witnessing, and also knew history was being made.”

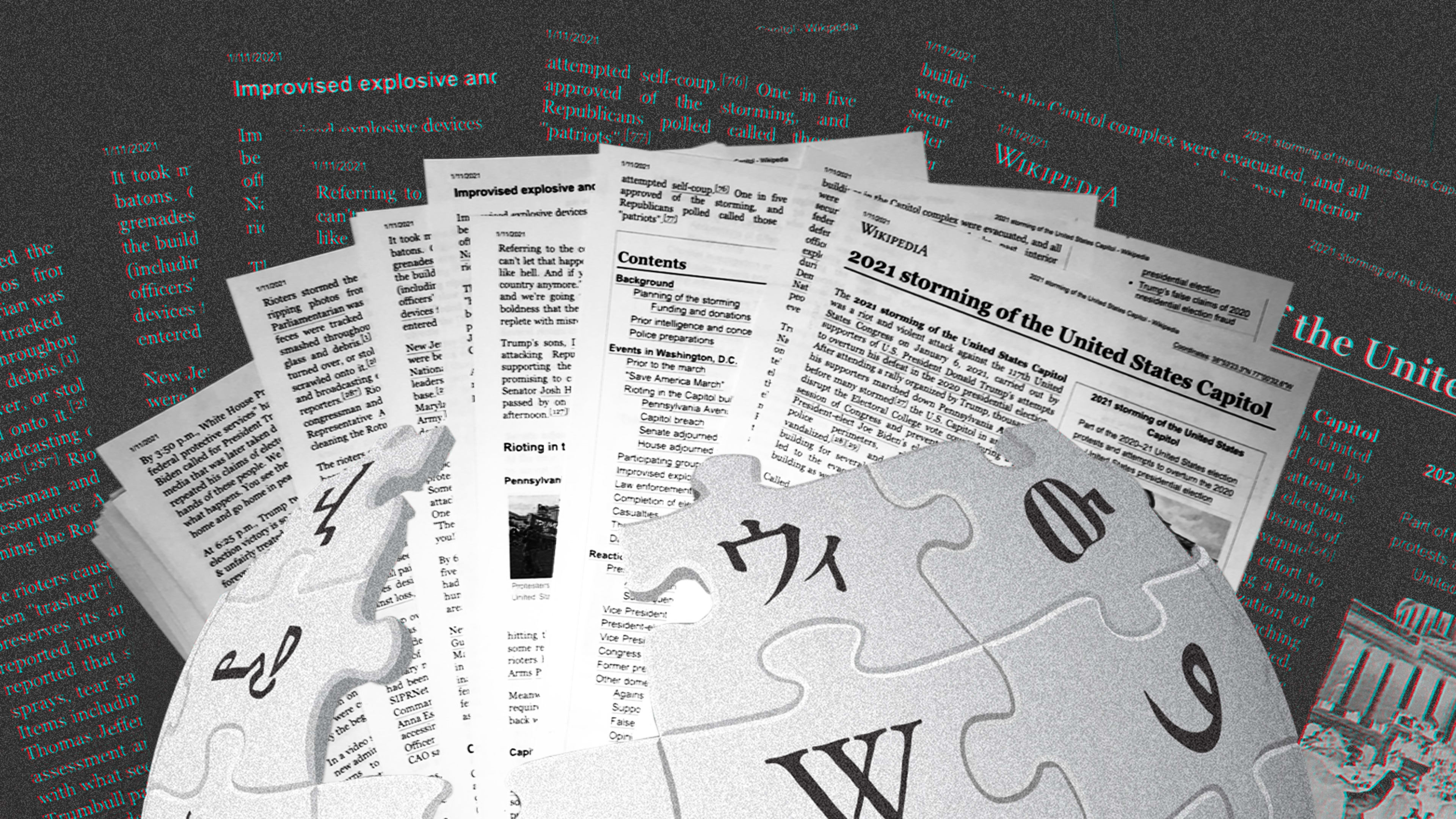

So he got to work. Moore is a veteran editor on Wikipedia, spending hours a day creating, shepherding, and policing articles. He started in 2007, ranging across topics of personal interest like music or architecture, but since early last year he’s been focused on the pandemic and political protests. Just after 1:30 p.m. EST, as rioters and police clashed at the bottom of the Capitol steps, he wrote, “On January 6, 2021, thousands of Donald Trump supporters gathered in Washington, D.C., to reject results of the November 2020 presidential election.” He appended links to a couple of sources deemed “reliable” by the community—NPR and The Washington Post—clicked save, and notified some other editors about his article. It was tentatively titled “January 2021 Donald Trump Rally.”

Was this really worthy of its own article, they asked? At that moment, protesters—rioters—were battling with police, both sides spraying chemicals. It was “hard to tell notability in the moment,” Moore wrote under his username, Another Believer. “But what we’re witnessing is unprecedented (like so many things lately).”

While riotous, misinformation-fueled mobs were breaking into the building—forcing lawmakers to evacuate, halting the counting of the Electoral College votes for several hours, and leaving several people dead—another kind of crowd began gathering to build upon Moore’s first sentence. After a brief trickle, Wikipedia veterans and newcomers quickly piled in, scrambling to add details, citations, and photos. On a popular Facebook group for editors, someone posted a warning to Wikipedians in D.C. who had gone to the scene to take photos: “Please please please be safe! Your life is more important than getting the perfect media for Commons.”

One admin soon changed the title from “Rally” to “Protest.” Another placed edit protections on the page to foil vandals. Debates erupted on the article’s Talk page, its public discussion room, as editors wrestled with many of the same hard questions breaking out in newsroom Slack channels across the country. This is no longer just a protest, but what is it?

As facts came in, as editors double-checked and pruned according to Wikipedia standards, the text grew and shrank and grew again, so that only the most relevant verifiable and neutral language remained. “Once other editors showed up to contribute, I aided, facilitated, and watched eagerly as the article developed,” says Moore.

At the peak of editing, there was a change being saved every 10 seconds, estimates Molly White, a software developer and longtime Wikipedia editor who began working on the article in its earliest minutes. From her desk in Cambridge, Mass., she’s been editing the page for hours every day since. “It was one of those things where I was shocked and horrified at the news as it was unfolding,” she says, “and felt like helping with the article was a more productive way to process everything than just doomscrolling.”

About 24 hours after the attack began, she and Moore and 406 other volunteers had crafted a detailed, even-keeled account of an event as it was unfolding—5,000 words long, with 305 references. Those numbers have since mushroomed, along with page views: 1.8 million and counting.

And that was only the English version: By Thursday morning, there were already articles in more than 40 different languages, including Esperanto.

People began looking for images to illustrate the article. The first, a photo of pro-Trump protesters outside of Union Station that was taken just before noon EST, was added to the article at 6:36 EST. https://t.co/CHA6RN0IJL pic.twitter.com/qB1X8CtiAo

— Molly White (@molly0xFFF) January 10, 2021

There’s an old joke about Wikipedia’s crowdsourced competence: Good thing it works in practice, because it sure doesn’t work in theory. “It’s particularly true,” White says, “when it comes to hundreds of people all trying to write about a current event in real time, as sources publish conflicting and sometimes inaccurate information.”

Still, the article—now stretching to more than 15,000 words, or 90 printed pages—is far from perfect. It’s the product of an editing community that tends to skew largely Western, white and male, with all of its biases and blind spots. Wrestling with those issues and testing each sentence for verifiability and neutrality can spark heated, incessant debate—especially when the facts amount to a reality that quite simply defies comprehension. And from the article’s first hours, nothing has been more divisive than the title itself.

The debate over a name

As police were finally pushing rioters out of the Capitol, a majority of editors agreed that the second title, “2021 Capitol Hill Protests,” had to be changed. But was this a riot, an attack, a siege, a self-coup, an insurrection? “The lack of organization seems to have similarities with the Beer Hall Putsch,” one editor wrote in the hours after the attack. Someone else insisted on “2021 United States coup d’état attempt,” and a few others agreed.

A few editors quoted from Wikipedia policy, WP:TITLE, which says articles should be named based on Recognizability, Naturalness, Precision, Conciseness and Consistency. Others pointed to a Wikipedia essay, “WP:COUP,” which explicitly says that the word should be avoided in a title “unless the term is widely used by reliable sources.” That evening, an editor named Spengouli noted, the Associated Press was advising journalists to “not refer to the events as a coup, as they do not see the objectives of the invasion as being overthrowing the government.”

Another editor chimed in with some alternatives: “the New York Times [is] using the words “riot” and “breach” as well as “storm”; CNN is using “riot” and “domestic terror attack”; Fox is calling it “Capitol riots.” (Fox News, Wikipedia’s current policy advises, “is generally reliable for news coverage on topics other than politics and science.”)

In the early hours of Thursday, as Senators reconvened to certify the election, a growing crowd on Wikipedia was pushing for insurrection. Even Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell had called it a “failed insurrection” on the floor of the Senate, someone said; soon, others pointed out, NPR and PBS were readily using the term too.

Still, others insisted that per Wikipedia guidance, insurrection is a legal term and should be used only after a ruling by a court or by a successful impeachment vote by the U.S. Senate. As EDG 543, a Chicago-based editor, wrote on Wednesday evening, “Biden, Romney, and a CNN opinion piece calling it an insurrection does not make it factual.” Someone argued the event didn’t meet the definition of insurrection in the Wiktionary, Wikipedia’s sister dictionary: “A violent uprising of part or all of a national population against the government or other authority.”

Except, as more details emerged, others said, it pretty much did meet that definition.

JulleTrying to define exactly what something like this is as it’s happening is probably beyond us.”

“Trying to define exactly what something like this is as it’s happening is probably beyond us,” Johan Jönsson, who goes by the handle Julle, wrote on Wednesday evening.

Frustration stretched the Talk page longer and longer. “Open your eyes!” one anonymous editor said. “This is an armed white supremacist insurrection by a mob intent on overthrowing the incoming democratically elected government and installing God-Emperor Trump as dictator for life, motherfuckers! Why some of you want this to be titled ‘rally,’ ‘protest,’ or ‘peaceful gathering of friends’ is beyond me.”

“Let’s take a deep breath,” wrote DenverCoder9 on Wednesday evening. “The best articles are written with a cool head and we should aspire to that standard.”

History’s crowdsourced front page

Wikipedia isn’t supposed to be a source for breaking news—Wikipedians explicitly say that the site is “not a newspaper.” Another oft-cited community guideline, WP:WINARS, insists, “Wikipedia is not a reliable source.”

“Wikipedia is a work in progress,” says Katherine Maher, CEO of the Wikimedia Foundation, the San Francisco-based nonprofit that operates Wikipedia. “And we always say it’s a perfect place to begin learning, but you definitely shouldn’t stop there.”

But many of us do: Wikipedia is now considered reliable enough to serve as something like a central clearinghouse for facts online. Google depends on it to build its knowledge graph, while Facebook and YouTube use it to provide users with contextual information around false content.

Wikipedia is now considered reliable enough to serve as something like a central clearinghouse for facts online.

In fact, Wikipedia began honing its ability to quickly make sense of things during its earliest days, in the aftermath of another shocking event. The website was born 20 years ago this month, a spin-off of a project by two entrepreneurs, Jimmy Wales and Larry Sanger. Nine months later, a group of terrorists crashed passenger jets into the World Trade Center. Someone started a Wikipedia article, and a fledgling, pseudonymous self-built community of editors flooded in. The September 11 attacks were momentous for the site, helping establish and solidify some of its core standards, says Brian Keegan, an assistant professor of information science at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Those standards include neutrality and verifiability but also those important rules about “what Wikipedia is not.” (“A Wikipedian’s primary role is as editor, not a compiler or archivist,” Animalparty reminded his colleagues on Monday night.) Twenty years later, says Keegan, coverage of breaking news topics like the coronavirus pandemic are still testing the Wikipedia community, and proving its surprising power.

“It seems even more contradictory when a bunch of volunteers, in the absence of any sort of centralized editing authority or sort of delegation or coordination, is still able to produce these especially high-quality articles,” he says.

When even neutrality can be political

As they watched tear gas wafting over the Capitol on TV, White and Moore jumped into ad hoc roles as quasi community organizers, shepherding conversations and handling a growing pile of edit conflicts and requests from users who didn’t have permission to edit the page directly. For sensitive pages like this one, admins can switch on additional safeguards that restrict editing to accounts that are more than 30 days old with more than 500 edits, requiring all other edits to be approved.

That didn’t stop the typical attempts at vandalism, falsehoods, and disinformation. “Mostly there are the anonymous ‘editors’ who vandalize or otherwise troll pages with high traffic,” says Moore, the sorts of bad edits he’d seen around COVID-19 and Black Lives Matter. “But also there are well-meaning people who are genuinely misinformed, and others who introduce bias, purposefully or unknowingly.”

Bad behavior doesn’t go far here. While social platforms like Facebook and Twitter have lately taken a harder approach to policy violations, for instance by banning Trump and others linked with the Capitol attack, Wikipedia has consistently been swift to close the accounts of bad actors. “There’s little appetite for feeding the trolls on the site,” says Moore. “There’s so much more important work to be done.”

On the article’s Talk page, editors shared news articles, aired concerns, and hashed out contentious edits, in theory according to the principles of “assume good faith” and “be polite.” On Wednesday, one visitor wrote a note of thanks. On Friday, someone who had attended the Trump rally beforehand sought to clarify the size of the crowd: “100s to less than 10,000” inside the Capitol, they wrote, and “easily tens to a hundred thousand” outside. By Sunday night, the discussion had flowered to more than 70 topics that ranged from formatting problems to questions about law, semantics, and philosophy. The crowd was processing this unthinkable event in open-source code.

The crowd was processing this unthinkable event in open-source code.

With each discussion came more editorial guidance from the sticklers: The names of criminal suspects do not belong in the encyclopedia; only the names of rioters convicted of crimes may be included. George R.R. Martin, a Reddit post, and an on-the-scene Instagram video are not reliable sources; in any case, Wikipedia relies only on secondary sources. Use more neutral, clearer language in general: Words like mob and baseless carry a value judgment; better to stick with rioters and false.

Were the people inside the Capitol best characterized as a “mob” or “rioters”? Were some merely “protesters”? Some editors urged caution with “rioters,” on the grounds that not all participants were violent. “We used the same logic to not call the George Floyd protests the George Floyd riots, because violent rioters do not take away from what peaceful protesters do,” Alfred the Lesser wrote on Thursday morning.

“What a load of horseshit,” wrote SkepticalRaptor, a nine-year Wikipedia veteran, on Sunday. “‘Protestors’ is a weasel word that makes these treasonous insurrectionists appear to be roughly equivalent to BLM protestors (who actually protested). This story is about the attempted coup and the terrorist infiltration of the Capitol. They weren’t protestors, they were terrorists. I even think ‘rioters’ is weasel wording. This seems like whitewashing that we’d find in Conservapedia. Disgusting.”

The battle over what words to use brought into stark relief a central distinction on Wikipedia: between what’s accurate and what fits into an encyclopedia, between what’s “true” and what’s verifiable.

“Wikipedia is about neutrality, so it’s very hard when there’s no neutral word,” DenverCoder9 told me in an email, after they had been furiously editing for spans of hours. “You can see the ungodly amount of edits. I’ve been editing [on Wikipedia] for a while”—at least 20 months— “and I’ve seen nothing like it before.”

But tame neutrality— or the appearance of neutrality— can also be the product of bias or ideology: There may have been a protest, but describing the people raging in and around the Capitol as “protesters” downplays the violence and vileness, their confused and ugly intent. Call a spade a spade, someone said.

The problem with ‘storming’

At 3 a.m. on Thursday, after more than 200 editors had weighed in, an admin changed the name of the article to “2021 storming of the United States Capitol.” It was a stopgap measure, wrote CaptainEek, not a permanent solution. “We say what sources say, and for the moment they seem to say ‘storming,'” they wrote.

“Whitewashing,” said an editor named Albertaont. “This isn’t some romantic Storming of the Bastille.” Many agreed. On Thursday, Joanne Freeman, a professor of American history at Yale, shared her disapproval on Twitter: “It romanticizes it. There are plenty of other words: Attacked, Mobbed, Vandalized. Use those instead. Words matter.”

Jill LeporeSo one good idea would be never, ever to call the Sixth of January ‘the Storming of the Capitol.’”

By Friday, a few editors pointed out, insurrection was one of the most used terms among reliable sources. Soon, Democrats were distributing articles of impeachment based on a charge of “incitement of insurrection.” A conviction by the Senate could add more credibility to the label.

Anyway, wrote Chronodm, a California-based editor, storming had other problems: “Given Stormfront and The Daily Stormer, not to mention QAnon’s repeated use of ‘storm”,’ I really don’t think it’s a neutral choice.” Someone dropped in a link to a New Yorker essay by Jill Lepore, who was also shaken by the Nazi and QAnon links. “So one good idea,” wrote Lepore, “would be never, ever to call the Sixth of January ‘the Storming of the Capitol.'”

But Lepore doesn’t edit Wikipedia. Other editors insisted that “storming” was an accurate enough description, and that Wikipedia doesn’t bend to Nazis. “We really shouldn’t consider these fringe groups,” DenverCoder9 replied on Friday. “They produce so much nonsense you can find an association for every word, even ‘OK.’ Consider words as meant by the average reader.”

Of course, it’s not always clear how Wikipedia’s average readers interpret words, or even who those readers are. And just as new details emerge, the use and meaning of words change. The point is that words matter, and so the debates and the edits continue.

Moore, the article’s first official author, expects the name to change again too, “as media outlets hone in on specific descriptions and words over time,” he says. He doesn’t have a strong opinion about it. “I am confident editors will determine the most appropriate name for the entry based on journalistic secondary coverage, as Wikipedia editors do.”

The Wikipedia article on the tragic 2021 Storming of the United States Capitol is 3 x longer and 3 x more referenced than the Wikipedia article on the triumph of the American Revolution. "Those who tell the stories rule society"-Plato. #Americans #January6th #Politics #BiasMuch pic.twitter.com/x9RR8IRVju

— Wade Burleson (@Wade_Burleson) January 12, 2021

There’s a lot of other work to do, says White: chronicling the injuries and deaths, the litigation, the reactions, the attempts to remove Trump. By Sunday, the article had reached 14,000 words, plus spin-offs, like a timeline of events and a compilation of international reactions. “And as time goes on we will also document if and how the incident has established a lasting place in history,” White says.

Like us, future historians will study the article to learn about what happened on January 6. And, as Slate‘s Stephen Harrison and others have previously pointed out, if they look at the behind-the-scenes debates over language, at these first (and second and third) drafts of history, they could also see how we processed the event in real time. The article’s Talk pages and edit histories could reveal things, says Keegan, “that are easily lost in historical accounts that pick up threads with the benefit of hindsight.”

What might those historians find? At an extraordinary moment of information collapse, broken trust, and violent tribalism, many different people with good intentions could still agree on the tragic reality of what happened—whatever we end up calling it.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.