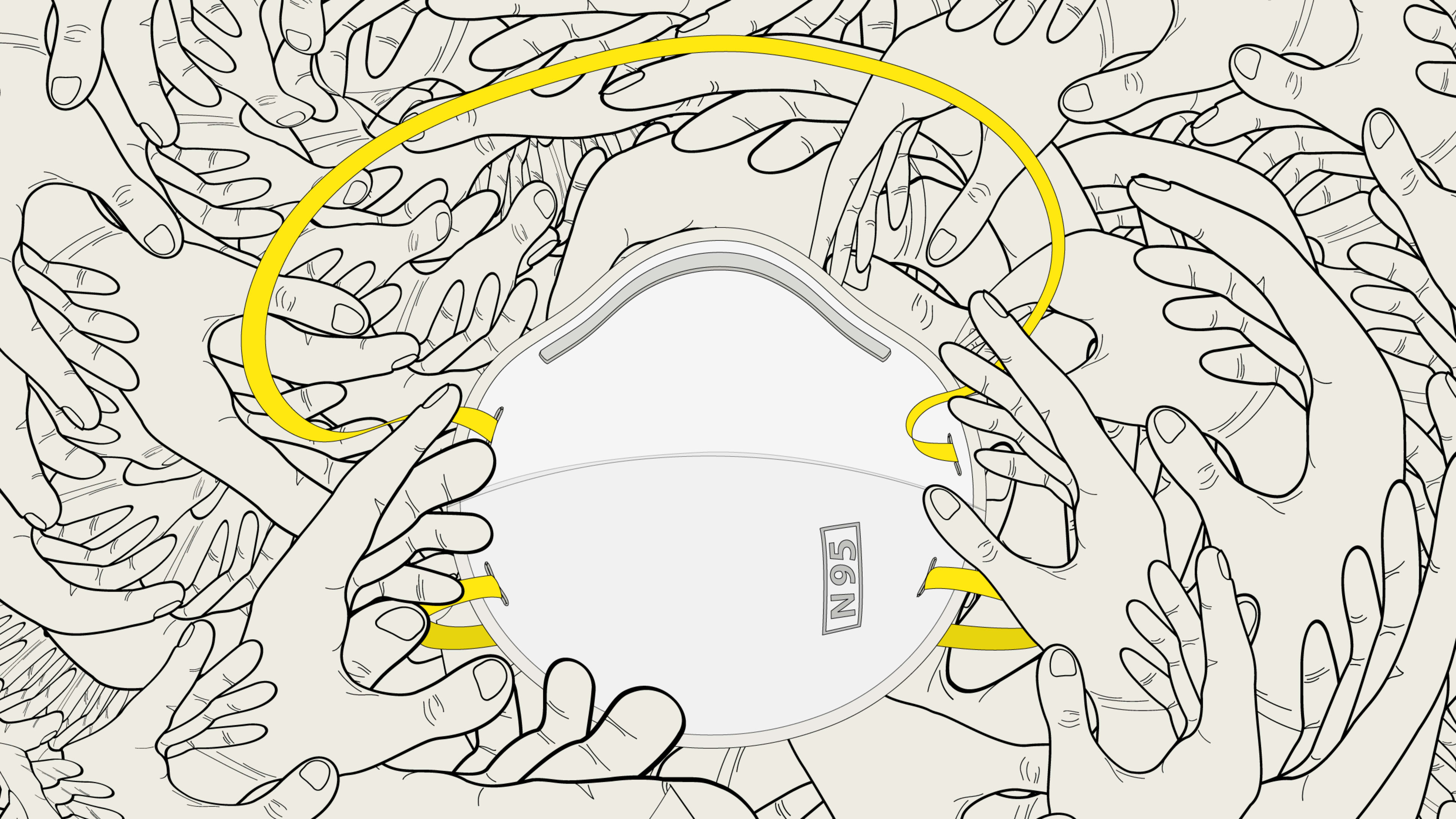

At the start of the pandemic, there was a sudden realization that hospitals did not have enough N95 respirators, the masks that are the industry standard to protect workers from respiratory illness. Because healthcare personnel working around COVID-19 patients needed many more N95s than usual, hospitals’ stockpiles weren’t large enough. The problem was so acute that members of the public were asked to donate N95s they had at home to hospitals.

Part of the reason the government took so long to recommend mask-wearing to the general public was a fear of creating a run on the remaining N95s. Now, around 10 months after the first COVID-19 cases began to spread in the U.S., as a new surge hits much of the country, little has changed: Doctors and nurses still don’t have enough. Clinics, especially small practices, are struggling to buy supplies. And many of those with masks on hand are still forced to reuse them.

“I talked with a woman at a clinic in St. Louis [last week], and she was saying that some of the staff have been using the same respirator for five months,” says Anne Miller, executive director of Project N95, a nonprofit that helps healthcare and essential workers access PPE. Beyond healthcare, there’s also a need for reliable masks that can be used by other essential workers, from teachers to grocery store clerks. In an ideal world, some argue, there would be enough N95s for use by everyone, since they are far more effective at preventing viral spread than cloth masks.

Instead, the problem is getting worse. Get Us PPE, another nonprofit working on the problem, says that the requests it receives for personal protective equipment have risen 240% from the same point last month. In November, the organization says that 61% of facilities were reporting shortages of PPE. Out of the healthcare workers who said they didn’t have enough N95 masks, 86% said that they were being forced to reuse them. “It’s really really pretty mind-blowing that in December, we’re still at the point where we’re subjecting healthcare workers to those kinds of unsafe conditions,” says executive director Shikha Gupta, who is also an MD.

The current surge in cases isn’t a surprise. So why are mask manufacturers like 3M still failing to meet demand—and why is it so difficult for workers to access the masks that are being made?

One challenge is the way the market is set up. Some suppliers limit purchases based on how much clinics have purchased in the past, so if a doctor’s office didn’t order many last year, they aren’t being allocated many now. Many suppliers also have high minimum orders, so it’s difficult for anyone other than large hospitals to meet those requirements.

“This spring, I was ordering N95s off of Amazon, because that’s the only place I could find them,” says Dr. Susan Bailey, president of the American Medical Association, who works in a small clinic with three physicians. “It’s not unusual for someone who sells PPE to have a minimum order of 5,000 to 10,000 units. And that’s not something that a small physician practice needs or can afford.”

Nonprofits have been trying to fill some of the gap; Project N95, for example, aggregates small orders from clinics, nursing homes, and other facilities to create large-volume orders of hundreds of thousands of masks, so it can negotiate better pricing. It also tries to address other access issues, such as how to cost-effectively get masks to remote locations like Alaska. Get Us PPE has focused primarily on coordinating donations of masks, both to healthcare workers and to facilities such as homeless shelters.

Even large hospitals often still don’t have adequate supply and are forcing staff to reuse masks. “Physicians, nurses, and other frontline providers risk their lives every day to take care of COVID patients, and they’re being asked to do things that they would have been disciplined for doing prior to the pandemic,” Bailey says. Fundamentally, there’s still a problem with supply.

The problem began before the pandemic started. The federal government didn’t fill the national stockpile of supplies that was supposed to be on hand for crises, despite repeated warnings that something like the COVID-19 pandemic was likely to happen. The Department of Health and Human Services funded the invention of equipment that could make 1.5 million N95s every day, but the Trump administration didn’t purchase it when the design was ready in 2018.

As COVID-19 began to spread in January of this year, the Trump administration declined an early offer from a manufacturer that could have produced millions of masks. The administration didn’t begin placing orders until March. And while the administration used the Defense Production Act to spur the production of ventilators, it made only limited use of the law for respirators.

The administration has claimed that N95 production is now sufficient, but the reality for workers on the ground is different. “The AMA has been calling, since the early days of the pandemic, for a federally operated tracking system for PPE so that we could follow the production, the allocation, and the distribution of PPE, so we would know where it’s all going,” Bailey says. “It’s clear that there are some federal officials that think that we have plenty of PPE, but my suspicion is that that PPE is going to large hospital systems and being stockpiled. And then the doctors and private practices still are having a hard time finding it.”

Project N95’s Miller says that she has spoken with large PPE manufacturers who also don’t know where their products are actually ending up.

3M has tripled production by activating unused production lines, but while a company spokesperson said that “the company has made extraordinary progress in increasing supply in a very short time period,” it still hasn’t been able to meet demand and has also said that the industry overall can’t provide sufficient supply.

“This information could have been shared much earlier in the year,” says Get Us PPE’s Gupta. “I think 3M is a large enough company that they would have been able to predict their production abilities pretty accurately, even several months before now. And in that time, there are many steps that could have been taken, but it’s really a missed opportunity. As we head into what is very likely going to be the worst part of the pandemic, the fact that we didn’t have that information ahead of time handicaps our healthcare providers and essential workers even more than the situation they were facing earlier in the year.”

As the Biden administration takes office, Gupta says that it can make full use of the Defense Production Act to ramp up production as much as possible, but new production lines take time to set up. The masks are relatively complex to manufacture and have to meet exacting standards, even for parts like the straps. (Most production now happens outside of the U.S., but there is still room for capacity to expand domestically.) “Even if Biden invokes that on day one of his tenure as president, by the time we have enough of a workflow set up to actually create production, it will take months,” Gupta says.

She argues that the government should also set up price controls and an objective system for rating manufacturers so that buyers can easily see which have been vetted (a system like this could also help people working outside of healthcare, who also need to better understand which masks are safest). High demand for masks will continue well into 2021. And the country will also have to figure out how to be better prepared for the next pandemic.

“I think every practice, every hospital, every system is going to be stockpiling PPE in the future,” Miller says. “And we’ll all have to decide how much we really need. Because we know that we can’t count on an overnight, just-in-time supply solution for PPE in the future.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.