As digital systems multiply across the urban landscape, they are producing immense streams of data that can help inform how we manage and plan cities. The potential now exists, at a scale previously unavailable, to directly measure issues that have been central to urban planning since its inception, such as equity, environment, value creation, service provision, public opinion, and the effects of physical form. But many city planners find their relationship with technology, data, and its use in communities to be an uneasy one.

The modern city was shaped by experiments with data analytics that can be traced back to the First Industrial Revolution. At that time, cities doubled in population as people flocked from the countryside to work in factories. With that growth came extreme poverty, a lack of proper housing and sanitation, and outbreaks of disease. Understanding the urban poor propelled early nineteenth-century data collection efforts, and all this new data gave birth to modern statistics and public health. These Victorian-era data scientists used their analytics as evidence for the development of modern sanitation systems and the need for light and air in housing—helping to create new building codes. Later, this same data, often visualized through maps, was deployed as evidence for the removal of whole neighborhoods and the strategic blighting of undesirable communities.

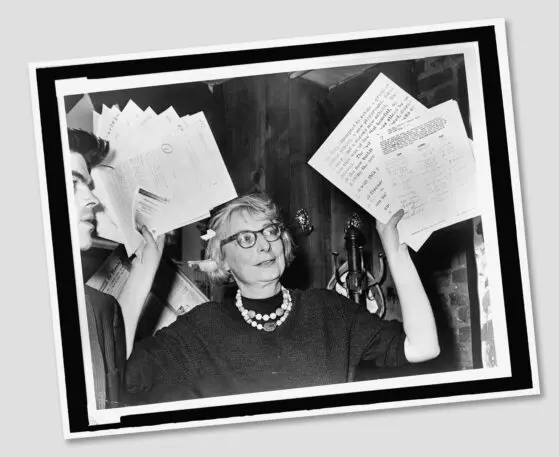

It’s interesting to note that Jacobs didn’t argue against data per se, but rather against how data was typically collected and analyzed. She was interested in understanding how the social connections of place created certain ties that strengthened the urban economy. These social ties are difficult to quantify, but qualitative data, including local stories and imagery, can be helpful in explaining them. Yet technocratic planners often relied solely on the data on the map to defend their ideas about the removal of perceived blight.

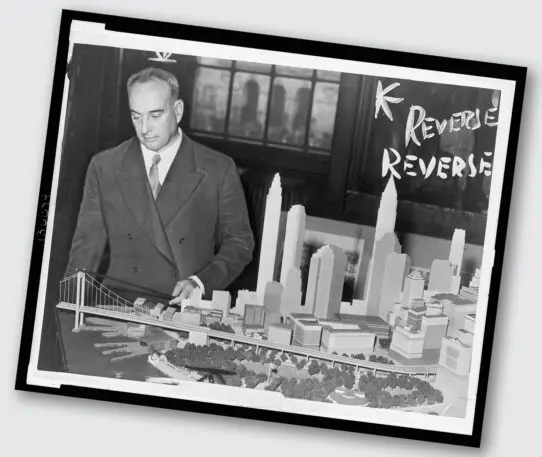

Jane Jacobs’ ideas about the city were often pitted against those of Robert Moses, New York City’s most influential planner. Moses has come to represent the technocratic planner whose main concern was making New York a “modern” city of highways and high-rises. Moses was able to deploy urban renewal strategies that effectively severed the community ties that Jacobs valued by using data as evidence, and also by producing the types of maps advocated by Bartholomew. Jacobs, in contrast, came to represent a more qualitative planner who understood that the social networks of people are what make the city a great place to live, and that preserving those social networks, which help build and maintain community, were a legitimate focus of the urban planner’s concern. For Jacobs, such social and support networks were often essential for low-income communities—and the modernist city as Moses envisioned posed a great threat to them.

Excerpted from Data Action: Using Data for Public Good by Sarah Williams. MIT University Press, 2020.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.