The book Hillbilly Elegy arrived just before America elected Donald Trump president, and Netflix’s version has now arrived just after America denied him a second term.

In the intervening years, many prominent Culture-Understanders have held up Hillbilly Elegy as an essential resource for decoding why the “white working class” overwhelmingly went for Trump. Now that this voting bloc’s hero has been soundly defeated, though, it’s not quite the most ideal time for a cinematic slice of Rust Belt misery porn. A great many pundits have spent the past four years asking the left to understand this group’s reasons for voting for Trump—and are doing so again right now—while much of the group apparently spent the past four years finding new reasons to vote for Trump again.

Even though the film version wisely excises the book’s more overt conservative propaganda, it’s the most polished version of this story at the moment everyone least needs to hear it.

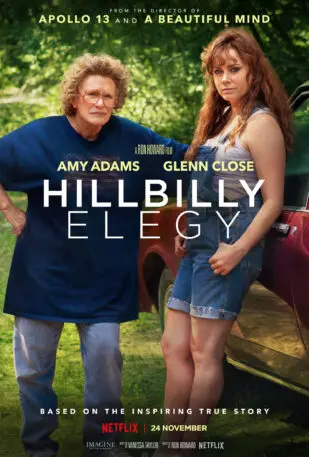

Hillbilly Elegy is a cultural hagiography written by venture capitalist and coal mine whisperer J.D. Vance about a hardscrabble youth spent between rural Kentucky and suburban Ohio. The book follows Vance from a colorful boyhood, in which he’s chased by his switchblade-bearing Uncle Teaberry, to his transformative time in the Marines and fish-out-of-water tenure at Yale Law School. Along the way, we meet his drug-addled mother, Bev (played in the movie by an Oscar-coveting Amy Adams) and his foul-mouthed, shit-kicking Mamaw (played by a trapped-in-a-Mad-TV-sketch Glenn Close), and the word hillbilly is uttered more times than anyone could reasonably be expected to endure.

The book’s main selling point, though, is its demystification of Appalachia dwellers at a moment when they were coming to symbolize the Forgotten Man. At least in part because of this incredible timing, Vance’s book went on to sell millions of copies and become assigned reading in a multitude of college courses.

Many of those mandatory readers may have been rightfully appalled, though.

The book’s major sins are the author’s frequent use of the royal We to speak for a diverse populace, the implication that the social problems plaguing Appalachia are exclusive to Appalachia, and the nonstop preaching of bootstrap-centric prosperity gospel.

These problems start right in the book’s subtitle, A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis—the author appointing himself as in-group spokesperson—and they spill over to practically every page. As historian Elizabeth Catte points out in her book What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia, “Nonwhite people, anyone with progressive politics, those who care about the environment, and LGBTQ individuals” do not exist in the world of Hillbilly Elegy. Nor would readers ever know that West Virginia has the nation’s highest concentration of trans teens.

But the most prominent issue at hand is Vance’s distaste for government handouts and his insistence that anyone who hasn’t transcended whatever circumstances they were born into has failed.

Poverty? A lack of jobs? Opioid addiction? Perhaps you are suffering from “learned helplessness,” rather than systemic inequality or any other external factors. Have you ever thought of that?

“These problems were not created by governments or corporations or anyone else,” Vance writes at one point of poor Appalachians whose lives are suspended in stasis. “We created them, only we can fix them.”

Never mind that his hillbilly brethren would have a better chance at self-actualizing if they weren’t hindered by prohibitive medical expenses and tuition costs. Vance once had a drug-addict neighbor who bought T-bone steaks with welfare money while Vance worked hard and presumably ate only saltines and raw crabgrass, so government handouts are definitively bad.

What’s insidious about putting such a premium on individual failure as an explanation for poverty, criminality, and drug use is that if conservatives have allowed themselves to accept this as canon for poor white people, imagine what they think about poor minority groups? (Many of whom, by the way, also have to worry about accidentally getting killed by police, in addition to many of the struggles Vance outlines.)

“Conservatives believed that Elegy would make their intellectual platforming about the moral failures of the poor colorblind in a way that would retroactively vindicate them for viciously deploying the same stereotypes against nonwhite people for decades,” Catte writes elsewhere in What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia.

Since Hillbilly Elegy on Netflix leaves out the most explicit conservative elements of the book—the welfare hate, a strained defense of predatory lending, and so forth—audiences are left with a very standard escaping-my-small-town story, with a frisson of Forgotten Man worship.

Some of the new scenes invented for the movie, however, make it equally detestable.

- Saving the turtle. In the opening scene, following rustic, idyllic shots of shirtless men in crumbling driveways with immobile pickup trucks, we meet Young J.D. (Owen Asztalos) carrying a turtle with a cracked shell through the woods. Another hillbilly child, perhaps one born with less stick-to-it-iveness than J.D., cruelly suggests that our hero either take the turtle out of his shell or see how far he can throw the little creature. J.D.’s response is how we learn that he is not only kind, but also knows the word carapace. The movie goes out of its way to show that Vance is special, in a way that Vance might have been too embarrassed to render himself on the page. Sure, it’s up to each individual to succeed in life, but it helps if the individual is inherently Good.

- Judging the friends. Once Mamaw eventually assumes legal guardianship over J.D., she refuses to let him hang out with his miscreant friends anymore. What exactly makes these friends irredeemable losers, under whose influence the impressionable but special J.D. fell, is never defined. When Mamaw chases two of them away with derogatory jokes about their Polish heritage, though, this ethnicity-based othering is coded as a playful and quirky heart-in-the-right-place gesture. Gross!

- Down with elites. In an early instance of the film’s nonlinear chronology, law school-age J.D. (Gabriel Basso) is out at a fancy dinner with a prospective white-shoe law firm. Upon finding out that J.D. comes from Appalachia, one of the partners can’t fathom the idea of someone going from Yale back to his hometown in the sticks. “It must feel like you’re from another planet,” he says. “Like, ‘Who are all these rednecks?'” The table suddenly gets quiet afterward, as J.D. informs them, “We don’t really use that term.” In this telling, all hillbillies are imbued with depth and nobility, even if the costuming on Glenn Close looks a little silly, but the elite gatekeepers on hand are Fox News caricatures dripping with contempt for all the bumpkins in flyover states. This character feels like a stand-in for Vance’s idea of “elites” altogether.

While part of the intent behind Hillbilly Elegy is to put a nuanced face on an old stereotype, one stereotype that both the book and film are only too glad to perpetuate is the stuffy, out-of-touch, quietly malevolent elite. Over the past four or five years, this nebulous term has come to mean “anyone in a blue state who hasn’t recently filed for bankruptcy.” It’s a group that Vance, echoing the average Trump supporter, appears to have never considered much beyond trying to excuse why it’s okay to loathe them.

“Sometimes I view members of the elite with an almost primal scorn,” Vance writes in Elegy. His disdain for this vaguely defined group—whom Swanson frozen foods heir Tucker Carlson implores his audience to hate every night—is mostly just annoying, but it can also get downright pernicious.

Speaking of Barack Obama at one point, he writes, “The president feels like an alien to many Middletonians for reasons that have nothing to do with skin color.” Instead, the stated reason for Rust Belters’ outsize objection to Obama is that he’s a well-educated, big-city elite who plays upon their deepest insecurities. “He’s a good father while many of us aren’t,” Vance writes with his beloved royal We. “He wears suits to his job while we wear overalls, if we’re lucky enough to have a job at all.”

This is all conjecture—Vance presumably didn’t conduct a scientific survey among Middletown, Ohio residents—but if the objection to Obama is mainly his status as an elite, how on earth does Vance explain the Appalachian attraction to Trump, a former game-show host and real estate mogul who was born rich, attended an Ivy League school, and lived in a penthouse before he lived in the White House? That’s a circle neither the book nor the movie attempts to square. While I would never accuse every coal country resident of being racist, I would say that this group’s stated animosity toward “elites” is rather confused and overly broad—and worth examining at length.

Coming so soon after this election, Hillbilly Elegy feels like a movie designed to celebrate the people partly responsible for Trump’s catastrophic first term. For a film so fixated on personal responsibility, though, it sure does let those people off the hook for a lot.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.