After living in New York City for more than a decade, Rob*, 35, didn’t think he’d be headed back to the suburbs. “I never thought that I would be moving home with my mom with no idea on what was next,” he says. But this unexpected reality hit at the end of summer, months into the pandemic, during which he lost his full-time job and started logging overtime hours at Whole Foods as an Amazon Prime Now Shopper.

In the wake of COVID-19, millions of Americans and thousands of U.S. businesses have faced extreme economic turmoil. Around 22 million American jobs were lost in March and April alone (and fewer than half have returned). Yelp data shows that at least 80,000 small businesses closed for good between March 1 and July 25. More continue to shutter, cut ties with employees, and struggle to pay for rental space.

But Rob’s employer, Amazon, which owns Whole Foods, hired more than 175,000 additional warehouse and delivery workers in March and April, defying the hiring freeze trend that befell businesses around the globe. After a short blip in its otherwise reliably well-stocked marketplace—Amazon was unprepared to deliver the ungodly amounts of hand sanitizer, toilet paper, and other goods for which customers flocked to the site for about a month—the e-commerce platform has emerged as a quarantine champ.

At the end of June, Amazon employed 876,800 people, an increase of 34% year over year. In July, CEO Jeff Bezos announced that his company’s workforce reached 1 million workers, including 175,000 temporary workers hired during the pandemic. But not all of these employees have had the same access to support, information, and a safe place to work. Conversations with two Amazon workers who are employed in different parts of the organization reveal a stark difference in the treatment of Amazon’s corporate, white-collar workers and the hundreds of thousands who are keeping its retail empire chugging along at risk to their own health.

Work from home versus work from hell

Rob, who spoke to Fast Company under condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation, started working part time as an Amazon Prime Now Shopper at Whole Foods well before the mayhem of the pandemic; in fall 2019 he took on some hours “as a side hustle, to make some extra money.” His main source of income from his commission-based sales job was falling as his company pivoted to a new industry. As sales began to dip, and then suddenly nosedived, Rob took on more hours with Amazon in February 2020. Soon he had abandoned his previous job and was working 50 to 60 hours per week shopping for people’s groceries. It wasn’t long before his side hustle became “essential”—both to his own welfare and that of his community.

“The day it got serious was right after the NBA canceled everything,” he says, referring to March 11, when it was announced that the 2019-2020 professional basketball season would be suspended until “further notice.” The following day, March 12, concert tours were canceled, Disney World was closed, and at least 1,663 cases of COVID-19 were confirmed in the U.S. At first, things at Whole Foods were chaotic, Rob says. “Nobody knew anything—there’s no playbook for this kind of stuff.”

Rob, Amazon Prime ShopperNobody knew anything—there’s no playbook for this kind of stuff.”

While workers like Rob were scrambling to understand what was going on with little communication from management, the situation at Amazon’s corporate offices was dramatically different. According to Stephen*, a 35-year-old manager in Amazon’s marketing department who also requested anonymity because he did not have permission from Amazon to speak to Fast Company, he and his colleagues received a first email from Amazon about the option to cut back on travel and to work from home on February 28. On March 3, they were sent a second, more direct email permitting employees to work from home. On March 9, Amazon mandated employees to work from home until further notice, he recalls. (An Amazon representative says that a first communication was sent to all employees on February 28.)

While anecdotal, comparing the lived experiences of Stephen and Rob during the pandemic reveals the differences in safety, communication, and support that two workers at the same company received throughout the first six months of the pandemic. As Amazon’s white-collar workers logged in remotely from the safety of their homes, and, as Stephen says, were equipped “with whatever we needed,” hundreds of thousands of warehouse and retail workers like Rob put their lives on the line to continue shipping products and delivering food to Amazon customers.

Rob says he and his fellow employees initially struggled to get sufficient personal protective equipment. At the onset of the pandemic, he remembers the stores were crowded and the employees were prohibited from wearing masks (this was around the time public health experts advised against wearing face coverings). “It wasn’t until late March, maybe early April, until they started handing out masks,” Rob says. “They didn’t make masks mandatory until they had enough to give out to [everyone].”

He points to the irony around safety practices: “One of the biggest things instilled in the job at Amazon was safety—they say stuff to protect themselves from lawsuits,” he says, explaining that safety messages, like reminders to bend at the knees when lifting something heavy, were hammered into the employees daily. “So then, when we had a real safety issue come up with this pandemic, nobody was doing anything.”

Amazon says it began rolling out social distancing and other safety measures starting the week of March 16. “Amazon prioritizes the safety and health of its employees and has invested millions of dollars to provide a safe workplace, which is why at the onset of the pandemic we moved quickly to make more than 150 COVID-19-related process changes including supplying masks, gloves, thermal cameras, thermometers, disinfectant spraying in buildings, increased janitorial teams, additional handwashing stations, hand sanitizer, and sanitizing wipes,” Amazon spokesperson Maria Boschetti told Fast Company in an email.

Rob says things got a bit smoother in the store as time passed. “All the supplies were there except for at the beginning,” he says. Reminders were sent to employees’ phones about staying six feet apart from one another, as well as information about steps to take if, for example, you had a fever. Rob says the company also provided services and support for employees, “like you could call a hotline if you were depressed.”

A lot of the guidelines were initially self-imposed by employees, but Rob says even after being reminded by text to keep six feet apart, there was a general understanding that “no matter what we do, it’s not going to be 100% safe.”

Rob, Amazon Prime ShopperNo matter what we do, it’s not going to be 100% safe.”

Amazon does make an effort to recognize the risk workers like Rob are taking. Importantly, the company provides up to two weeks of paid sick leave for Whole Foods employees who test positive or are presumed to be positive for the coronavirus. In March, all Whole Foods and Amazon warehouse employees were given a pay raise of $2 per hour and double overtime wages; Rob’s hourly wage went from $15.90 to $17.90. “It mattered, definitely,” he says of the increase. But he and his coworkers could never be sure how long the hazard pay would last. “They told us they were going to end it three different times before they finally ended it on June 1. Everything went back to normal like the pandemic was over.”

Amazon told Fast Company that it returned to its standard hourly wages of $15 per hour when demand stabilized. This demand does not appear to be related to the risk workers still face. The company did not address whether it plans to bring back hazard pay, especially as coronavirus cases soar across the country.

“To thank employees and help meet increased demand, we have paid our team and partners nearly $800 million in increased compensation since COVID-19 started while continuing to offer full benefits from day one of employment,” Boschetti said. “This included a special one-time thank-you bonus totaling over $500 million that was issued to all frontline employees and partners who were with the company throughout the month of June.”

Rob says the reduction in hazard pay was particularly galling, considering he could have earned a similar amount of money not working and collecting unemployment instead—which, at the time, was boosted by an extra $600 as part of the government’s stimulus package. “All of us could have just stayed home and gotten unemployment, making the same money we were making working 50 to 60 hours a week risking our lives.”

Stephen, the marketing manager, says he never feared contracting the virus in any kind of professional setting. “We never worried about being put in a harm’s way situation or being exposed to other folks. Amazon was very forgiving in terms of not having people go back to work.”

Risking workers for the bottom line

While its white-collar workforce was given early instruction to telecommute, Amazon’s other wage earners were still clocking in, in person. This had devastating consequences: As of October, more than 20,000 U.S.-based Amazon employees had been infected by the virus, many of whom work on their feet at warehouses or, like Rob, in retail stores.

Stephen, Amazon marketing managerWe never worried about being put in a harm’s way situation or being exposed to other folks.”

On November 12, former Amazon employee Christian Smalls filed a class-action lawsuit against the company, alleging that Amazon violated federal civil rights law by firing him and by putting thousands of warehouse employees, particularly employees of color, at risk during the pandemic. Smalls was fired by Amazon after leading a protest outside a fulfillment center in Staten Island, which, Smalls said, was intended to shed light on the unsafe working conditions throughout the pandemic. Amazon says Smalls was fired for violating quarantine and social distancing rules.

One reason for the discrepancy in how Amazon has treated its workers is obvious: It’s easy for coders and marketers to work from home, while delivery drivers and warehouse workers don’t have that same luxury. Without physical bodies showing up to work, there would be no hands to pack puzzles into brown boxes and no person on the other end of an app to stuff pasta and canned goods into shopping bags.

Amazon doesn’t choose to have its employees infected, but in a sense the company is resigned to letting it happen, says Brad Hershbein, a senior economist at the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research. “If some of [the] workers do get sick, [Amazon doesn’t] think it’s going to be a deal breaker in terms of their production flow. They know people are looking for jobs and they’re one of the only companies ramping up hiring. If someone does get sick, it’s not a disaster,” he says, alluding to the dispensability that plagues many workers of the gig economy. (Given Amazon’s 2018 decision to raise its minimum wage to $15 an hour, its full-time jobs pay better than other standard low-wage jobs.)

“Anything that’s going to [halt production] is a business decision,” Hershbein says, pointing out that companies of all sizes face these sorts of decisions on a smaller scale every day. Plus, “it’s more costly to safeguard some workers than others,” he says, explaining that transitioning white-collar workers to telework is relatively easy, while enforcing new safety standards for a dispersed group of workers “when they’re several chains down is hard to monitor.”

Brad Hershbein, W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment ResearchIt’s more costly to safeguard some workers than others.”

Another reason a company like Amazon might treat different groups of its workers so differently is a matter of technicality. Many of Amazon’s warehouse workers and shoppers are employees, like Rob, but the company also outsources some of its jobs—particularly for delivery drivers—from other companies, or brings people on as independent contractors. This arrangement allows Amazon to avoid responsibility for these workers’ well-being: One 2019 investigation, for example, revealed that outsourced Amazon drivers were steered to risk their livelihood and that of others—skipping meals, bathroom breaks, and rest—in order to fulfill Amazon’s promise of next-day delivery, while Amazon was able to dodge any real liability.

Outsourced and independent workers are in a precarious position. But despite Rob’s position as a part-time employee at the beginning of the pandemic (and even when he later successfully transitioned to a full-time employee), he often felt unsure that he could trust Amazon to be transparent about how the virus was affecting its workforce.

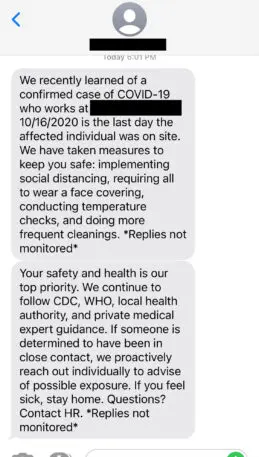

That manifested primarily through the company’s contact tracing system, which Rob says was far from perfect. “They weren’t telling us people were testing positive in the beginning. Then there was a text message system. . . . We’d get texts everyday that someone tested positive at a certain site. They would reach out to you personally that you would have to quarantine for two weeks, and they’d pay you [if you came into contact with the person who tested positive].”

The problem with this method, Rob says, is that many Amazon Prime Shoppers work at multiple stores throughout a week, meaning they come into contact with entirely different groups of employees and customers. “When somebody tested positive, there’s a lot of crossover between stores,” he says. It’s unclear to him whether this crossover is taken into consideration when the company decides who has to quarantine. “I don’t really blame them for that,” he says of the lack of communication, since if everyone was told to quarantine, “then nobody’s at work.”

Amazon says that it follows all guidance for contact tracing from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and local health authorities. The company says that if a person who has worked at multiple locations tests positive, each location is notified and contact tracing is conducted for any close contacts.

Stephen, Amazon marketing managerIf anything, I’ve just been proud to be able to work for a company that’s been as forward-thinking as Amazon.”

In contrast, Stephen and his team have received consistent communication from what he calls an Amazon “task force” dedicated to all things COVID-19, especially early on. “Upper management would schedule weekly or biweekly sessions where as a team we would talk about the current state and we would ask any questions and we would always get really positive responses or really forward-thinking responses from our leadership group,” he says. “Amazon keeps internal websites that they update, so I’d say once every day or two we’d have updates on the situation. It’d be like a full FAQ with status updates.”

Stephen says that the pandemic has only highlighted Amazon’s agility. “We always had the preparations in place for technology to advance into where it is now,” he says. “The pandemic accelerated that. . . . I think it just validated what Jeff Bezos had always envisioned and wanted to build for his company. If anything, I’ve just been proud to be able to work for a company that’s been as forward-thinking as Amazon.”

Stratified success

In the process of moving back in with his mother this summer, Rob was able to transition from working as a part-time employee in New York City stores to a store in a more suburban area, where he has since secured a full-time role with benefits, including health insurance. None of this represents the direction Rob imagined his career would be headed, but as he puts it, “it’s hard to get positions right now” because of the virus. “I’m gonna move on, but I’ve taken a break from job searching since I’ve moved home.”

For all of its success, Amazon has hardly spread its wealth evenly among its employees. The stratification between its white-collar workforce and its warehouse or retail counterparts is closely reflective of America’s own economic disparities, which have only been widened by the pandemic.

Rob wonders if he were to have this experience again whether he’d just take the unemployment money and stay home. “Actually, I probably wouldn’t have, because I felt a sense of doing something to help the community. But it’s fucked up that people who were sitting home were making more money than people who were out there doing stuff.”

*Both names have been changed to protect anonymity.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.