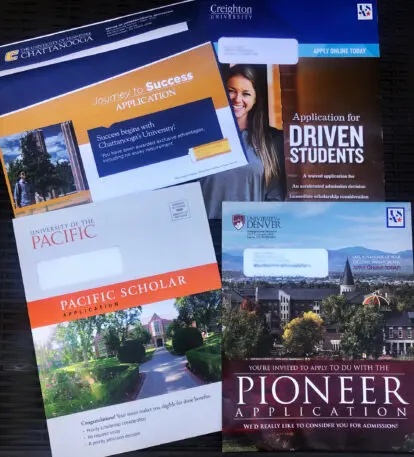

The glossy college brochure has become a rite of passage for many Americans. Parents groan as leaflits fill boxes in bedrooms and cover kitchen tables. Teenagers marvel at the attention from admissions departments in far-flung locales.

Behind the scenes, of course, is a massive data-harvesting operation. A student’s name is sold, on average, 18 times over her high school career—sales leads for a marketing funnel worth billions of dollars.

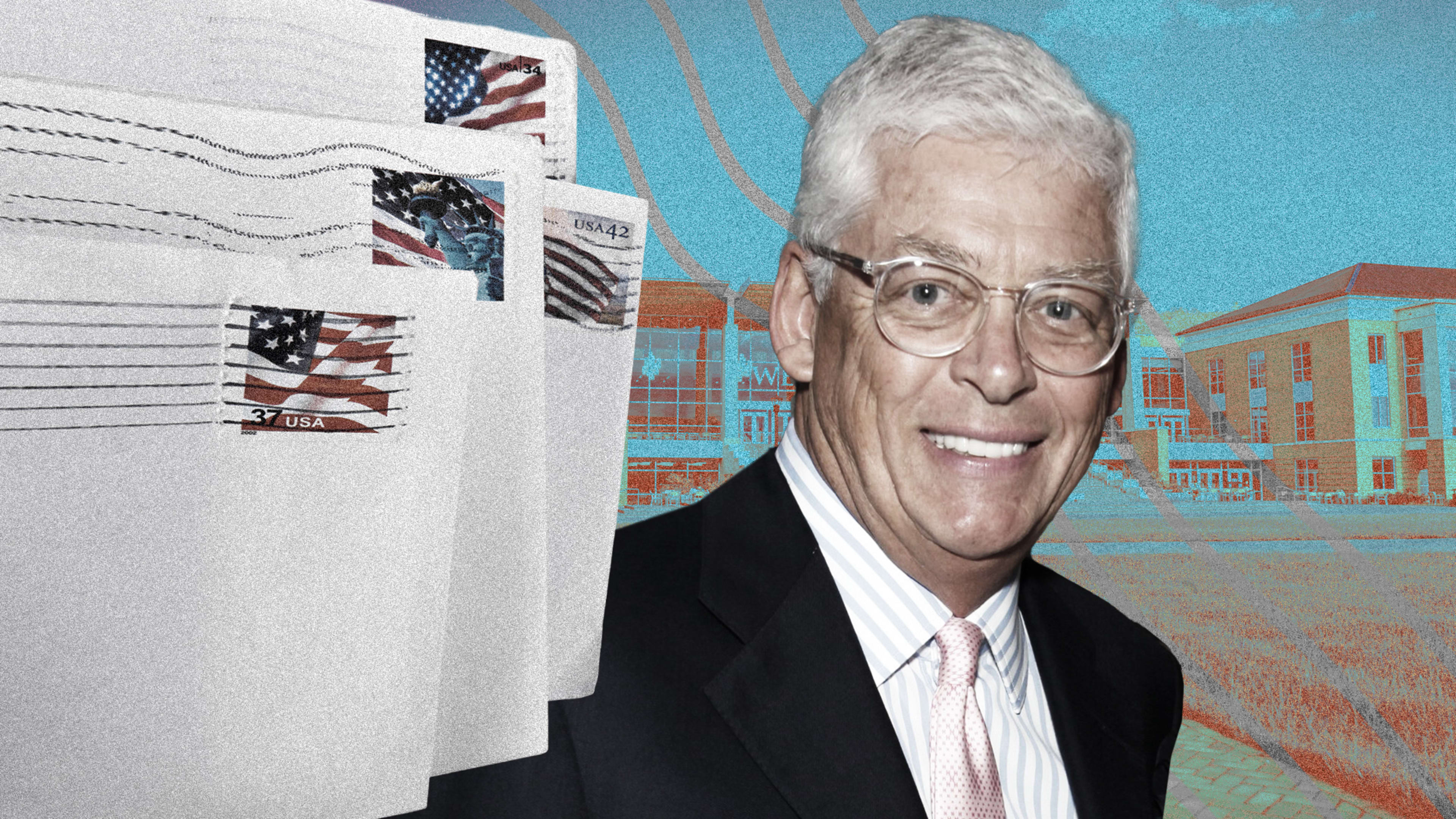

It was probably inevitable, in the age of Google and Salesforce, that colleges would find a way into our email boxes. But every innovation needs its Thomas Edison, the person who sees around the corner and speeds change up. For college marketing, that man was Bill Royall.

The moment that changed everything took place on a spring day in 1988, at a conference having nothing to do with colleges. Bill Royall’s direct mail firm in Richmond, Virginia, didn’t have any higher education clients back then; he worked with politicians and with nonprofit organizations that needed to raise money. He had come to Washington, D.C., to talk with people who ran New England summer camps.

The camps wanted to expand their geographic reach, and they invited Royall to the meeting to talk about how direct mail might help in attracting new families. While political campaigns were Royall’s focus, he told the summer camp leaders that direct mail was increasingly an effective tool for selling all kinds of products. There was no difference, he said, between hawking a candidate for Congress and peddling a summer camp to parents.

But Royall’s pitch that day fell flat. “They weren’t interested, at all,” he told me in an interview in 2019.

After the speech, as Royall waited for the elevator at the Capital Hilton, a man approached him. He introduced himself as Robert Jones, the admissions director at Hampden-Sydney College, a private all-men’s college in Virginia. He had heard Royall’s speech and asked if he had ever managed mailings for colleges. “We didn’t have any clients in higher education,” Royall recalled telling him, “but there was no reason we couldn’t.”

A few months later, Hampden-Sydney hired Royall & Company. When Bill Royall started digging into the college’s marketing strategy, he was stunned not only by how the Virginia campus recruited students but also by what seemed to be common practices among many other schools, as well. Colleges purchased names of high schoolers much as they do today, but they were buying what Royall considered tiny quantities, limited to the names of juniors. Hampden-Sydney, for instance, bought only the names of students enrolled in private high schools. Most of all, Royall found that too many colleges waited for students to contact them instead of flooding the market with mailings to gin up interest.

The campus brochure, of course, existed long before Bill Royall signed up Hampton-Sydney as his first college customer. What Royall perfected was making the colorful college “viewbook,” as it’s known, as commonplace in the mailboxes of American teenage homes as an L.L.Bean catalog—and then ensuring the colleges he represented were on the top of the pile. Whether you call it junk mail, spam, or propaganda, generations of high school students and their parents have been inundated with images of manicured campuses and promises of supportive professors because Royall and those who followed his lead persuaded impressionable seventeen-year-olds that a college actually wanted them.

But what the schools really desired were students to apply in order to boost application numbers and make the colleges look popular to other teenagers, alumni, and the rankings. Sure, some applicants would get accepted, but the more who applied and the fewer who got in, the better for the school’s reputation.

If you’re a high school student or a parent of one, don’t be easily enamored or swayed by all the mail colleges send to your home or your email box. Because while there is a science to why you’re getting so much, the randomness of the strategy is more than just calculated—it’s deeply cynical.

* * *

College admissions is a big business. Colleges and universities spend an estimated $10 billion annually on recruiting students—mostly with old-fashioned direct mail and email, using tactics not much different than those of credit card companies and clothing retailers. Yet at its core, college admissions remains defined by rituals developed in the middle of the last century for a far smaller undergraduate population and for students who tended to stay closer to home than their modern counterparts. If you’re a parent and marvel at how different your kid’s college search is from your own, consider that it’s based on a system designed primarily for their grandparents’ generation.

In the years around World War II, students typically applied to one school, and most colleges admitted anyone who graduated from high school. Colleges we refer to today as elite depended heavily on feeder high schools, usually boarding schools, where officials understood the academic standards and knew the student body. Until the 1950s, colleges didn’t have an admissions office to speak of. There were no admissions deans. No viewbooks the size of catalogs mailed unsolicited to would-be students. No official campus tours. Instead, an administrator split his or her time between admissions and academic duties with the help of a clerical worker.

A student’s name is sold, on average, 18 times over her high school career, and some names have been purchased more than 70 times—all at a cost of 45 cents a name.

By the 1960s, the modern admissions infrastructure started to take shape, the result of more high school students knocking on the doors of colleges. The number of undergraduates more than doubled in the decade baby boomers arrived on campuses, to 8 million by 1969.

With increased choices for students, public and private colleges began competing for them, shifting the admissions conversation from recruitment to selection. In 1959, the College Board published for the first time what had been previously a closely guarded secret: how many applications a school received and how many students it accepted. The term “selectivity” entered the lexicon of college admissions.

As high school students learned about acceptance rates, they began applying to multiple schools to play it safe. Multiple applications prompted unease within admissions offices, which until then had never developed models to predict which applicants would enroll—because usually everyone who accepted came.

But even as admissions officers complained about the rising application volume, they stoked the fire to keep fueling the numbers. They did so by going on more high school visits to woo counselors who they worried would start discouraging students from applying to colleges with declining acceptance rates.

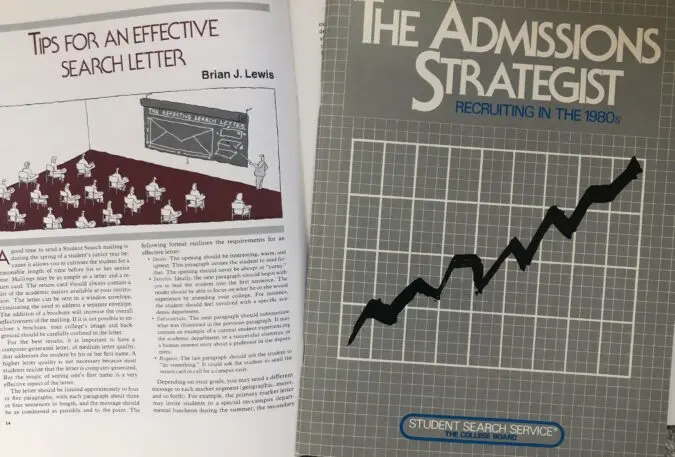

Even so, one tactic remained largely unused by colleges until the 1970s: direct marketing.

In general, colleges tended to wait for students to come to them. When Jack Maguire started as Boston College’s admissions dean in the fall of 1971, he sat with his secretary to watch what she did when a prospective student called to request information about the school. “She took out an eight-and-a-half-by-eleven envelope, dictated the name and address on it from the phone, stuffed the envelope and put it in the out-basket,” he recalled. “I said, ‘Wait a minute, aren’t you going to keep a record of that name?’ and she said, ‘No, if they’re interested, they’ll apply and then we’ll have a record.’ ”

That same year, the College Board offered a new service to campuses that would, over the subsequent decades, revolutionize how millions of high schoolers searched for colleges. It was called the Student Search Service, and it sold the names and addresses of test takers—in other words, prospective students—to admissions offices. The service got off to a slow start. Colleges didn’t think they needed to market to students.

But as the 1980s began, attitudes shifted. The last wave of the baby boom generation was leaving higher education. Demographics are destiny for colleges, and analysts projected that the number of U.S. students graduating from high school would shrink for much of the next decade and beyond. Schools needed to fill the classrooms and dorms they had built for the baby boomers, and marketing consultants such as Bill Royall were ready to help them do it.

When Royall got to work at Hampden-Sydney College, he took a page from the playbook he was already using to raise money for politicians and nonprofits.

Other new ideas followed, each one validated with a randomized experiment. One-page letters instead of two. Sending to juniors in high school as well as seniors. Window envelopes to speed up the mailing process so envelopes didn’t have to be matched with letters. An “offer” of free admissions tips if students returned the reply card.

“Everyone was resistant to the offer,” Royall told me. “It sounded cheesy, they said. It wouldn’t generate good inquiries from students. We told them more inquiries could get them better inquiries.”

Later, Royall convinced his clients to allow teenagers to mail those cards to a centralized facility run by his company to speed up the process even further and to better track responses. This was after Royall discovered some colleges stored inquiries from high school sophomores in a closet for up to a year before entering them in their databases because they couldn’t keep up with the responses. Most colleges were accustomed to using small consulting firms headed by former academics to run their marketing campaigns, and some colleges even mailed their own materials. Speed often wasn’t a priority until Royall came along.

* * *

If you’re a high school student deluged with mail from colleges on a daily basis, it’s because the College Board has your name. Most people know the College Board as the owner of the SAT. Founded in 1900, the organization counts some six thousand colleges, high schools, and nonprofit groups among its members. While legally a nonprofit, it often feels and acts like a giant corporation. It collected one billion dollars in revenue in 2017, according to its federal tax forms, mostly in fees for the SAT and AP tests.

The idea of selling the names and addresses of test takers started with a noble intent—to increase access to college by putting information in the hands of students who historically didn’t go. But as campuses competed aggressively for new undergraduates in the 1980s, peddling names turned into a moneymaker. By then, the College Board was selling 30 million names a year, at 14 cents a name and grossing $4 million.

In the 1990s, marketing consultants urged colleges to cast wider nets to find would-be applicants, upping the number of names purchased yet again. Then in the last decade, as email marketing and year-round outreach was introduced earlier in students’ high school careers, the College Board expanded further, selling names as many times as it could.

In 2006, the College Board sold 60 million names. By 2010, 80 million names were licensed, even though only 5.2 million students took the SAT and PSAT that year. Exactly how much name-selling has grown since is unclear. The College Board refuses to disclose how many names it now sells through “search,” as the practice is commonly called in the world of admissions.

Here’s what the College Board would tell me: search is bigger than ever. It sells names to nearly 2,000 colleges and scholarship organizations, up from 1,600 a decade ago. A student’s name is sold, on average, 18 times over her high school career, and some names have been purchased more than 70 times—all at a cost now of 45 cents a name, each time it’s requested among those test takers who opt in (students have the choice to participate). While the College Board was the first to sell names, they are far from the only one doing so these days. One survey of admissions officers found that they buy prospects from over a dozen sources, although the lists from the College Board remain the most popular, with the PSAT typically supplying freshman, sophomore, and junior names, and the SAT senior names.

When colleges buy names, they can filter the purchase by a variety of factors. An admissions office, for example, might order the names of men with PSAT test scores above 1200 who live in Pennsylvania and want to major in the humanities. This again is where a college’s agenda—and not the talent or accomplishments of students—drives the search buy. A college isn’t looking to send mail only to straight-A students who scored a 1500 or higher on the SAT. Campuses have certain needs—more men, more minority students, more English majors, more students from five states away—priorities they attempt to fulfill by buying names fitting those criteria. The information used to compile the search order is gleaned from questionnaires students complete when they register for a test.

The search business has allowed the College Board to add millions to its bottom line each year without doing much more than pressing a button to send names to colleges and their marketing consultants. While the College Board governs the use of the names under licensing agreements with colleges, the group hasn’t curtailed the endless stream of marketing to students—marketing that ultimately whips teenagers into a frenzy every year and warps the eventual value of the college search.

* * *

In the late 1990s, Royall & Company had plenty of competitors. Twice a year, all the firms would all ramp up staff and wait for FedEx boxes to arrive from the College Board with nine-inch reel tapes embedded with names of test takers.

For Bill Royall, even FedEx wasn’t fast enough anymore.

One summer afternoon in 1997, he sent a twin-engine Beechcraft Baron to New Jersey to intercept the tape delivery from a FedEx processing center near Newark airport. What was in those boxes was gold for the colleges that were Royall’s clients. Every minute mattered. The sooner he pulled those tapes out of the boxes and got those personalized letters in the mail the sooner those students would know that these colleges wanted them to apply.

In New Jersey, two men—one the Beechcraft’s pilot and the other a Royall executive—loaded 150 boxes into the back of their aircraft, the seats removed to make enough room. As the sun set, the prop-plane was cleared for takeoff on its return to Richmond. When it landed, Bill Royall met the aircraft and its precious cargo on the tarmac. The men transferred the boxes into a waiting truck and the group sped off on the thirty-minute drive to Royall’s headquarters.

Despite the late hour, the office was full. Workers opened each box revealing the stacks of tapes, each with a slice of student names purchased by a specific client. Royall employees confirmed the names on each of the tapes and repacked them for a short trip to a mail-processing firm in nearby Lynchburg. There, workers fed the reels into a machine that spit out letters addressed to each of the students by their first name. The letters included other personal details—their intended major, interests in school—and the all-important tear-off reply card. If students returned the card, they would get some sort of gift, usually a list of admissions tips.

A few weeks later, Bill Royall’s phone started to ring steadily with calls from clients, letting him know his strategy had succeeded—mountains of reply cards were arriving on their campuses every day. For several years, admissions consultants like Royall had pressed colleges to get mail out to prospective students ever faster. In an increasingly competitive market for students, speed was obviously more critical than ever before. From now on, Royall told his team, he wanted his schools to be first in the mailboxes of students—before they had a chance to fall in love with another college.

* * *

Line up students in a high school who performed similarly on the PSAT or SAT and ask about the letters, postcards, or emails they’ve received from colleges and you’ll immediately see how arbitrary the search business is.

If who gets mail and who doesn’t seems so random, it’s because it often is. A typical college’s search request usually exceeds how much it can afford to buy. An admissions office might want all the students in Colorado who scored better than a 1300 on the SAT—a request that might generate 12,000 names when the school can afford only 5,000 of them. As a result, the college receives an arbitrary selection of 5,000 names fitting its criteria. This haphazard process for fulfilling orders is why two high school students living in the same town, attending the same high school with similar interests, grades, and test scores might receive mail from different colleges. So while this marketing feels personal to many students who have little experience being sold to, it’s often no more personal than the Internet ads that chase us around the web trying to sell shoes.

No matter the medium, however, teenagers ignore the vast majority of marketing from colleges: only 11 percent elicits some sort of response (that’s considered good by comparison to direct mail for consumer products where the response rate is even lower). The consensus among the high school students and parents I met is that colleges send way too much mail—and most of it ends up in the recycling bin or ignored in email boxes.

So why send so much?

Schools flood the market with mail for many different reasons. They want to make themselves look more selective to the outside world. They’re uncertain about who is actually going to apply, so perhaps they want you to get a brochure but their interest has declined by the time your application is reviewed. What’s more, selective colleges are always looking for that needle in a haystack—the talented student from a middle-of-nowhere high school that they hope will be among a stack of search names they buy. Most of all, colleges want students able to pay, so schools tend to overbuy names of test takers from wealthy zip codes.

One mother texted me a picture of three milk crates of unopened mail she collected over the course of her daughter’s junior and senior years. Another joked that she planned to wallpaper her son’s room with the discarded mail when he left for college. A Reddit user tallied 2,374 marketing emails he received from more than 100 colleges—an average of 19 unsolicited emails from each school. Louisiana State University alone sent him 102 messages.

It seems some schools recruit you just so they can reject you. Why do they bother if we don’t have a chance?”

While occasionally a letter, a brochure, or the offer of college swag might grab the attention of a teenager—Harvey Mudd in a recent year sent a deck of cards for a scavenger hunt—the mail students told me they most often opened was from schools already on their radar.

Nevertheless, it seems everyone can recall receiving that surprise letter or email from an Ivy League school or another name-brand college, even when their stats were below freshman averages for the campus. “I got an email from Princeton,” a senior proudly told me when I visited her Maryland high school. The student with a 3.7 GPA and a 1350 SAT score showed me the message, which encouraged her to apply to take advantage of “the tremendous opportunities” Princeton offered to students like her. She sent her application because she thought she was being recruited. She was denied. “It seems some schools recruit you,” she said later, “just so they can reject you. Why do they bother if we don’t have a chance?”

The name-buying and resulting direct mail are both a cause and symptom of our national obsession with selective schools. Sure, selectivity was a measure of a college’s brand well before the College Board ever sold a test taker’s name, but the ease and frequency of direct mail changed the dynamics of student recruitment. It allowed colleges in every corner of the country to flood the mailboxes of high school students nationwide, enticing them with pretty pictures to new locales. Suddenly, a high school student in Massachusetts could know about a college in Minnesota or imagine herself walking across a campus in California.

The result was an uptick in applications to colleges, everywhere. Back in 1975, 60 percent of students applied to just one or two colleges. That was the norm. Now those students are in a distinct minority—only 18 percent do that. When I applied to college in the early 1990s, fewer than 1 in 10 students applied to at least seven colleges. Now that number, thanks to marketing and the growth of the Common Application, has exploded: some 1 in 3 students apply to seven or more places.

What’s more, the number of students crossing borders to go to college has more than doubled in seven states since 2008 (Arizona, California, Georgia, Mississippi, Nevada, North Carolina, and Texas). Over the last half century, the concept of distance has changed in the minds of college-going students and their parents. Places that once felt far away now feel as if they are one town over, thanks to the Internet, the ease of interstate travel, and the proliferation of discount airlines. High-achieving students—rather than settling for their local institution—started to jump into applicant pools at schools with national brands.

This re-sorting is largely why today’s admissions process seems so intensely competitive and anxiety-ridden to parents who went to college in the 1980s. It’s not that there are so many more top-notch students applying to college; it’s that the top ones from Los Angeles and Chicago and Atlanta and Buffalo are now all applying to the same selective schools. And they’re applying to way more of them.

* * *

The coronavirus pandemic has resulted in the cancellation of hundreds of thousands of SAT and ACT tests since the spring of 2020. While students and parents are worried about getting a test score to submit with their college application this fall, the College Board and ACT are concerned about their search business. After all, if tests aren’t given, there are no names to sell.

Even before the virus, however, colleges were already looking for new ways of finding students beyond the traditional name buy and were beginning to employ the same digital strategies that Amazon, Zappos, Netflix, and other online retailers uses to offer you other things you might like based on your past selections.

From his office at the University of Toledo, William Pierce, an associate vice president, watches visitors arrive. But he’s not looking out his window at campus. Instead, he’s peering at a dashboard on his desktop computer. The feed is constantly scrolling with visitors to the university’s website. They are tracked using their unique IP address.

The visitors arrive one after another, nearly every second. The first is Anonymous 5325015 from Toledo, Ohio. Another is Anonymous 9025345 from Sweet Home, Oregon. The third is a hit: David H. from La Porte, Indiana. He’s visiting the freshman tuition web page.

The day I’m watching, most visitors are anonymous. Pierce digs deeper on one of them, looking at the “engagement summary” that reveals this person—or at least this particular IP address—has visited the university’s website eight times over the last month, looking at thirty-two pages. Each click is a digital breadcrumb that follows the user through the website, compiling every movement as he advances.

Every so often, a pop-up appears—a small box in the bottom right-hand corner of the screen or an image that covers most of the page. The goal is to collect some tidbit of information from this user. A name and email address are enough at first. Then perhaps another pop-up at another time will collect information on intended major or year in school. Once Pierce’s system has a name, it’s added to the university’s customer relations management system, or CRM, which Toledo, like most colleges, uses to track prospective students and to serve them customized information. Sometimes the former anonymous user is already in the CRM system because the university had purchased the name and contact information through search. That’s a precious commodity to people like Pierce because now he can customize what he sends to that prospective student based on his web behavior.

But that’s not the only way Pierce uncovers his web visitors. Remember David H. from Indiana? He was revealed to the University of Toledo a different way. All those emails Toledo sends to would-be students from their name buys contain unique links. When David clicked on one, his data was connected to the back end of Pierce’s system. Now the system could track the movements of students like David through the university’s website and target them with personalized communications based on their interests.

Toledo’s software is designed by Capture Higher Ed. More than fifty colleges and universities use the Louisville, Kentucky–based company’s system, including the University of Kansas, the University of Tennessee, and Colby College. In a recent year, the company tracked 20 million unique web visitors on its clients’ sites. Most of that traffic is what is called “organic,” meaning it’s prospective students searching colleges’ websites without being contacted by the schools.

“Colleges have plenty of interested students, but they often don’t know who they are,” said Thom Golden, Capture’s former vice president for data science. “This tool helps universities uncover those students.” About 7 percent of users go on to complete interest forms that pop up on university websites served by Capture. Of those, 70 percent are organic visitors.

* * *

In June, Bill Royall died. He was 74. When I visited him in Richmond, Virginia, a little more than a year earlier, we met in a mostly empty, stark-white office he still maintained in his former company’s headquarters. In December 2014, the Advisory Board Company, which had made billions consulting in the health-care industry, bought Royall & Company for $850 million. The colossal purchase price sent shock waves through college admissions offices everywhere even though they had helped feed the beast. After all, most college endowments aren’t that large. In 2017, Royall & Company was sold again as part of a larger deal to a private equity firm.

Royall seemed riveted by his own story when he described it to me. I asked him how he felt about the ways the college search had turned into a seemingly never-ending process fueled by millions of pieces of mail and billions of dollars. He had no regrets for his role in creating the admissions monster. “Look, we’ve been able to contribute to access and opportunity and inclusion,” he said. “We know of thousands of kids who go to college every year who wouldn’t because they got recruited through us. When I look back on my legacy, to me that’s the greatest contribution that our company made.”

The business of marketing colleges made Bill Royall a very rich man. As I waited for him and his wife, Pam, whom he met at work, I flipped through a book in the reception area that profiled “the art of Royall & Company.” Sculptures, paintings, and photographs hang everywhere around the three buildings that make up the office complex in Richmond, all collected by the Royalls over the years. In the preface to the book, the company’s art director remarked that our perspective on art “changes as we learn more about its context.” Quoting from John Steinbeck, he wrote “we like what we know.” The same could be said for Royall’s approach to selling colleges. He tried to widen the perspective of students, so that they might like more than what they knew.

Above all, Bill Royall made himself wealthy by realizing that all those teenagers (and their parents) were customers. When people told him not to send “window envelopes” because families might think it was a utility bill, he knew they were wrong. Teenagers had never received a bill in their life. They were thrilled to be sold to. For the first time, someone was reaching out directly to them, sending them mail, talking about changing their lives. That type of marketing altered the way parents and their children thought about going to college.

For many Americans, being a high school student now means swimming in a constant stream of messages about colleges, debating options all over the country, wading through stacks of mail, and getting tracked while you visit college websites. In the end, Royall didn’t just expand the horizons for students—he expanded our collective anxiety.

Excerpted from WHO GETS IN AND WHY by Jeffrey Selingo. Copyright © 2020 by Jeffrey Selingo. Reprinted with permission of Scribner, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Correction: An earlier version of this article stated that Bill Royall died in July. He passed away in June.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.