In cities across the United States, racism exists in built form. There’s a long history of intentionally racist policies such as race-restricted covenants preventing minority groups from moving to certain areas, and redlining that limited access to housing finance and concentrated nonwhite residents in neighborhoods that were then systematically underserved. These policies have had long-term negative impacts on access to jobs, wealth creation, health, and countless other socioeconomic factors.

But even when they haven’t been overtly racist, urban development policies and practices have often neglected or harmed communities of color simply by cutting them out of the decision-making process. From community meetings scheduled at times that are difficult for working people to attend to preservation efforts that associate historical value with economic prosperity, many of the ways design and development happens in cities is rooted in practices that tend to disenfranchise Black communities and other nonwhite groups. They continue to result in discriminatory outcomes, whether planners, designers, and developers realize it or not.

“Unfortunately most people who work on this day-to-day aren’t necessarily thinking about ‘How do I work, why do I work the way that I work?’ And it has grave consequences actually for Black presence in public space and Black people generally that people are not interrogating the practice of how they work,” says Emma Osore, one of the founders of BlackSpace and the director of community at the New Museum’s cultural incubator, New Inc. “It’s important what we do, but I think one of our messages is the process by which you do them is as important as whatever the outcome is.”

This reckoning may be overdue, but it’s also not entirely surprising that it’s taken so long. The urban planning, architecture and development fields are notoriously white. Only 2% of licensed architects are Black. As of 2016, less than 15% of the American Planning Association’s members identify as people of color. More diverse representation in these professions would help, but demographic shifts are slow. Members of BlackSpace argue that more immediate change is needed in how these professions function.

Unlearning the toxicity of the design and planning profession

BlackSpace is now a formal nonprofit, but it developed into an organization only gradually. The first spark was a unique conference at Harvard in 2015 that brought together a wide range of Black designers, planners, and professionals working in the built environment. Organized by the African American Student Union at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, the conference was called Black in Design, and was for many attendees the first such gathering focusing specifically on design from a Black viewpoint.

“As folks from disparate fields, we weren’t used to seeing this interdisciplinary group focused on various ideas of Blackness across time and space,” says Osore. “We were so enamored by the ways we were learning, the types of things we were learning, and the people in the room. And we realized we want more of this. We want to get together across disciplines to center Blackness in public space or in space.”

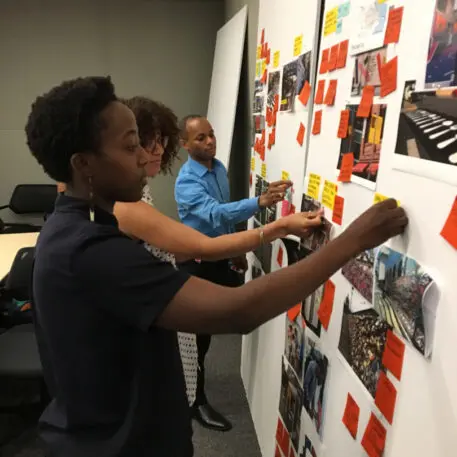

As it turned out, several of the conference attendees were based in New York and happened to live within close distance in Brooklyn. To try to keep up the momentum from the conference, they decided to meet again. This turned into regular brunches hosted at different apartments, and grew into an expanding circle of Black architects, planners, and designers. Osore says it was part brainstorm but also part support group. “The trust building and the community building and the brunches was also us taking the time to be in a safe space to unlearn a lot of the toxicity of the design and planning profession,” she says. “It was like a safe space to vent or share things that were not going well, or the experience of being the only one in the room, or how should I feel about X.”

Justin Garrett Moore, executive director of New York City’s Public Design Commission, was another of the conference attendees and early brunch participants. He says the conversations quickly morphed into what the group members could do to change things now. “We realized that we did want to have more agency and power, frankly, in the conversations,” he says. “Forming a collective, forming an infrastructure to support each other but also to support some of the changes that we all knew and understood needed to be made in these various fields and disciplines needed to happen.”

This led to the creation of the BlackSpace manifesto, a 14-point guide to the ways the organization wants to see its work happen. Its principles include ideas like “Plan With, Design With,” which emphasizes working with communities rather than attempting to represent them, “Reckon with the Past to Build the Future,” which acknowledges historical injustices as well as victories in undoing them, and “Move at the Speed of Trust,” which calls for taking then necessary time on projects to include people and earn their trust.

Putting new principles to work

These principles were put into action recently when the borough of Manhattan decided to create a large-scale street mural as part of the Black Lives Matter movement. BlackSpace members worked to ensure the process of designing and painting the mural aligned with the principles of the movement.

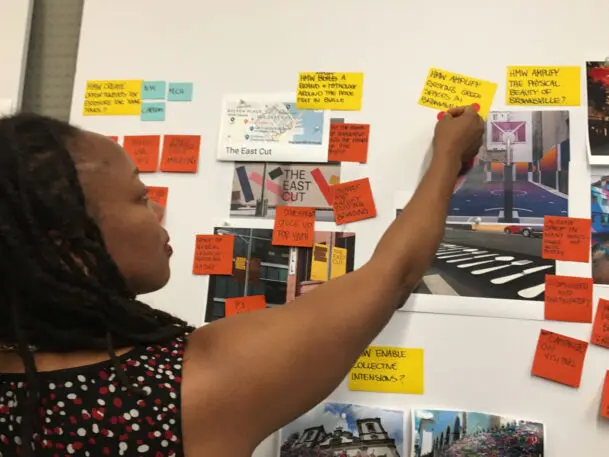

One of the other places BlackSpace has been most active is the historically Black neighborhood of Brownsville in Brooklyn with a high concentration of public housing developments and roughly $1 billion in development looming. “The planning community often jumps into neighborhoods with an idea and then forces community engagement into that. And that was something we wanted to make sure not to do,” says Kenyatta McLean, another BlackSpace founder. She’s currently pursuing a master’s degree in urban planning at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and spent years working in economic and community development. She says BlackSpace has been engaging with the community there to ensure that longtime residents have a say in how the neighborhood will change–and how its history can be preserved.

“It was an idea to take what happened in the historic preservation world that’s typically associated with wealthier and white communities but adapt it to the context that we saw in Black neighborhoods,” Moore says. “That Black spaces, Black culture were also worth valuing in that way as heritage and something that needed to be preserved and conserved.”

This work has been conducted over the years in close collaboration with organizations from within the community, including Youth Design Center (formerly Made In Brownsville), a Brownsville-based nonprofit that trains youth in marketable science, technology, engineering, arts, and math skills. Founder Quardean Lewis-Allen has helped convene other local groups, and young designers from his organization were commissioned by BlackSpace to design and produce the heritage conservation tool kit that can be used by other groups to collect more local histories.

Lewis-Allen says BlackSpace’s approach has been a refreshing change in Brownsville compared to the way development has been pursued in the past. “Everything that they’re proposing, that we’ve been doing, is not new information. It’s just that oftentimes we’re not in the positions of power to implement these strategies, or the folks who are implementing them don’t look like the communities they’re serving,” he says.

BlackSpace expands outside of New York

Many places see room for improvement on this front. Two official BlackSpace affiliate groups have formed in Chicago and Oklahoma City, and Osore says designers and planners in other cities have expressed interest in becoming part of the network. “I would like to say they invited BlackSpace in, but I think it was more like they demanded that BlackSpace be in their city,” she says, laughing. “We’ve had interest from all over the country, in every region. It’s not just a coastal thing. It resonates in Oklahoma and Atlanta and Detroit and Indianapolis and L.A., and that I think is something really quite unique and exciting about this work.”

Vanessa Morrison is a social planner and crisis response professional based in Oklahoma City, and she learned about BlackSpace during a presentation by the group at the second iteration of the Black in Design conference at Harvard, in 2017. She says she immediately knew she wanted to bring that effort back with her to Oklahoma.

“Most planning and design frameworks, in both academia and formal practice, have been exclusionary of Black culture, history, and communities. There has also been an extreme deficit in engaging and understanding the lived experiences of Black people and how they exist within their community spaces,” she writes in an emailed response. The BlackSpace aims to disrupt these systemically oppressive practices, she says, “by centering the voices of our community and creating opportunities for liberation through the built environment.”

Morrison partnered with Gina Sofola, a longtime development consultant whom she met in the University of Oklahoma’s urban planning master’s program. They reached out to BlackSpace organization in New York and set out to bring its ethos to Oklahoma, a state with a rich Black history and deep systemic racism. “I would find myself over the years at planning events or charrettes and working with the community, and the City of Oklahoma City just seemed to have a very difficult time penetrating and getting to the African American community in the way that they needed to and wanted to,” she says. “The African American community really had no confidence in the city’s commitment to work on their behalf, regardless of who their councilperson was. There were too many broken promises.”

Over the past two years, BlackSpace Oklahoma has been leading its own workshops and planning exercises, particularly in predominantly Black Northeast Oklahoma City, which has seen an increase in development in recent years. In an effort to make sure that history isn’t lost as development happens, they’ve been leading storytelling workshops aimed at preserving the area’s history in a more formal way. For example, Sofola says, not many people realize that there were 51 Black-incorporated townships in Oklahoma. They’ve partnered with the local library system and the University of Oklahoma to preserve these histories. Sofola says this work has filled a huge gap in the way the city understands itself.

“What we have done is just be about the business of getting busy for our community, and saying if no one else is going to advocate for our community, we are,” she says. “Because we’re African American, we understand what’s necessary, we can communicate with our community and they feel comfortable communicating with us.”

As a nonprofit, BlackSpace often relies on its network of members to spread its principles through their own work. Being a manifesto-based organization means that there doesn’t have to be a specific BlackSpace workshop or design event for its ideas to take root. “That’s how we will continue to show up in the world,” McLean says.

Moore, in the City of New York’s Public Design Commission, says the principles of the manifesto are now ingrained in the way he approaches his job, which has jurisdiction over all buildings and art proposed on city-owned property. “We’ve seen a lot of affordable housing development projects where we’re pushing for better consideration of a number of different concerns that affect Black communities. A big conversation that we have is about value and quality. The insistence that Black people deserve excellence too is a challenging conversation but one that we push very actively at the Design Commission,” he says.

This approach to urban planning and design is one that’s become even more pressing in recent months, as more people gain a broader understanding of how the built environment can exacerbate inequality. Osore says BlackSpace is trying to create a new way for these historic and persistent problems to be solved. “It’s part of a different ethical model to operate under. And in this moment or in these last many moments, when there’s so much uncertainty and opportunity for new ways of working, people are searching for new ideas that provide a path forward,” she says. “I think it has a lot of possibility.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the final deadline, June 7.

Sign up for Brands That Matter notifications here.