When he was still just 11 years old, the Roblox player known as Dazzely enjoyed games the old-fashioned way: He played them.

Back in 2012, Roblox, the massive online gaming platform, had plenty to offer him. He created his first avatar for free, styled its cylindrical head and clothed its blocky body. Then, choosing from the list of over a million titles on Roblox.com, Dazzely placed the little man in one game after another: He jumped him through obstacle courses, buckled him into race cars, and built him forts. Using free software called Roblox Studio, Dazzely could even construct his own games. That was the idea: Roblox’s creators envisioned the platform as a vast and ever-changing digital playground where kids crafted whatever they desired—games, clothing, structures, landscapes.

Dazzely continued playing Roblox as he grew up, and the platform matured with him. In 2013, Roblox introduced a way to convert its virtual currency, Robux, back into real dollars. A primitive economy—developers peddling virtual items like sunglasses or limited edition hats—evolved into a more complex one. Older kids began working for one another and performing specialized roles, as artists, builders, and game scripters.

It wasn’t the floor plan that caught his attention. It was the writhing crowd of naked Roblox avatars.

Roblox today is the product of its over 150 million monthly active users. What began as a sandbox now resembles a scrappy cybernation of teens and tweens whose population rivals that of Japan. And the dollars are real: Players poured more than $490 million into Roblox via mobile devices in the first half of 2020 alone, according to Sensor Tower data. Roblox projects that its user-developers—many of whom are Roblox veterans in their late teens and early twenties—will earn more than $250 million from selling access to their creations this year. The company, which is valued at $4 billion, takes roughly 65 cents of every U.S. dollar when developers cash out.

Dazzely, who is now 19 and whose real name is Dylan Lemus-Olson, holds a unique occupation in this booming super-metropolis: He’s a muckraking YouTube personality. Part tabloid reporter, part internet troll, he pokes around Roblox’s dark corners and uploads his exploits to the video platform, where he has more than 53,000 subscribers. As it turns out, there are plenty of shadows for him to explore.

For Dazzely, it was a push notification on a school night in 2017 that knocked him tumbling into Roblox’s red light district—a direct message via Discord, the online chat application that’s frequently used by gamers. The text contained a hyperlink to a Roblox game called, simply, “The Condo.” Dazzely hesitated briefly, then clicked.

They were the same blocky-headed, Lego-esque characters as in all Roblox games. Except these avatars sported profanely exaggerated anatomies, and the speech bubbles above their heads were a lurid cloud of curse words and slurs. Freedom of speech wasn’t the only thing these pixelated hedonists were exercising, either.

Someone must have hacked the Roblox child safety filters, Dazzely concluded.

He hit a button to start recording his screen. He leaned into his computer’s microphone and began to provide humorous narration for his then-nascent YouTube channel. The following morning, when Dazzely logged into his YouTube account and saw that his video had already received 1,000 views, Roblox stopped being child’s play for him. He had found his calling.

To the uninitiated, 21st-century gaming resembles its 16-bit past in one respect, at least: Players still mash controllers and keyboards to make characters run around the screen. But games today do more than kill time. They anchor teeming reefs of social life. Fans play together inside the games themselves, but they also school around adjacent sites—streaming their gameplay for one another on Twitch, posting videos on YouTube, sharing memes via Discord. Titles as ancient as Super Mario Brothers now support flourishing communities online (Google “Kaizo Mario”). But the games that inspire some of the most vibrant ecosystems are the massively open ones where users make their own fun—Minecraft, Fortnite, and, especially, Roblox.

For David Baszucki, Roblox’s cocreator and longtime CEO, this sprawling social world is the game’s best feature, and a sign of the media metaverse to come. Platforms like Roblox represent “a new category of human co-experience and freedom” he says, one that blends video games and social media. “We’re in this unique opportunity to be its shepherds.”

That means overseeing a world that’s filled with children. Though Roblox doesn’t disclose the ages of its users, it does say that the majority of them are under 18—and that at least half of U.S. kids ages 16 and under are on the platform. A December 2017 study by Comscore found that kids between the ages of 5 and 9 spend more time playing Roblox than doing anything else online on PCs; for those between the ages of 9 and 18, only YouTube consumes more of their online attention.

At a time of social distancing, that’s not necessarily a bad thing. Child development specialists increasingly see these multiplayer spaces as a source of lessons for kids about social rules, teamwork, and self-regulation. Online games and their adjacent video-streaming and chat sites also engender a sense of belonging and camaraderie. “We have to understand games the same way we understand playground play,” says Jordan Shapiro, a psychology researcher at Temple University and author of The New Childhood.

Indeed, many kids arrive on Roblox determined to play their favorite kind of make-believe: pretending at adult life. Games simulating grownup activities, such as caring for pets and babies (“Adopt Me!”), getting jobs (“Working at a Pizza Place”), and driving cars (“Jailbreak,” “Driving Simulator”), collectively rack up tens of billions of visits.

Kids between the ages of 5 and 9 spend more time playing Roblox than doing anything else online on PCs.

“We want kids to have an opportunity for free play,” Baszucki says. “Roblox allows them to get together, make their own rules, go together wherever they might want . . . and create together, build together, and in many cases, learn together.” But as the leaders of Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube have learned, maintaining control of a platform as it grows up isn’t easy. And Roblox, which turns 16 in September, has the added challenge of chaperoning a platform tailor-made for young users who love tinkering with software.

“Roblox is where I learned to hack,” says Quinn Wilton, a security researcher who spent her childhood playing the game and now works at the software security firm Synopsys. Given the choice between facing off against professional hackers or a mob of unruly teens, Wilton says she’d pick the former every time. “A teenager is hacking for ego, fame, respect—and they have endless amounts of time,” she says.

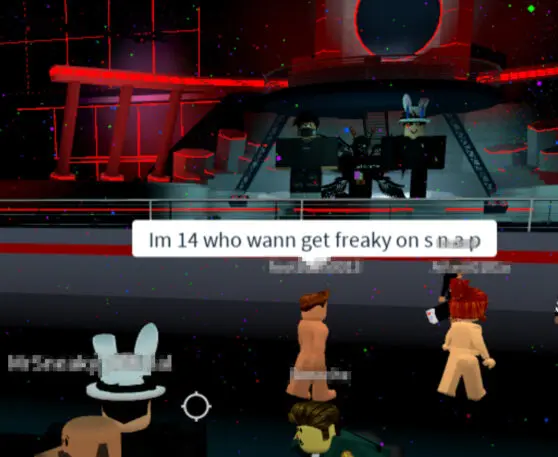

Kids test boundaries, and teenage desires don’t fit neatly into terms of service. On Roblox, these digitally savvy adolescents are growing up fast—and putting their avatars and themselves in dangerous positions.

It was 7 a.m. eastern on a May morning, and in a Roblox game titled “Haha~~;)” only a few players meandered around the palm tree-lined pool at a party house created by a group known as The Cons. In real life, this house might have functioned as a corporate event space—one could imagine its airy foyer filled with executives in chinos and name tags, nursing bad red wine. The Cons clearly envisioned their guests getting down to adult business as well, albeit of a different sort. Their den showcased an array of sex toys. The private rooms upstairs were furnished only with beds. The basement was a torch-lit sex dungeon.

[Video: Fast Company]New players started this Roblox game with a choice: “Boy,” “Girl,” or “other.” Selecting one of the first two options immediately stripped your clothes and transported you poolside; clicking “other” placed you, clothed, in the room with sex toys. Avatars could choose among more than 25 different body positions and movements—most of them simulating sex acts. (Males could also, incongruously, choose “pushups.”) Beer and boom boxes were available too.

The Haha house would eventually be visited by players more than 600 times in its few hours of existence, but for now it was relatively quiet. Inside, the only soul stirring was a solitary male figure in the home’s open-concept kitchen, recumbent on the breakfast bar. Judging by the motions proximate to his pelvis polygons, he was pleasuring himself. Elsewhere in the house, a player requested a private game server with another—so they could enter an identical, empty copy of the party house and carry on their interactions alone.

Roblox has been praised by child safety advocates for its dedication to safeguarding users. It maintains strict in-game rules, among them: no cyberbullying and harassment; no discriminatory, threatening, or overly violent behavior; and no looking for dates or engaging in sexual behavior of any kind. Players under 13 (you must enter a birthdate to create an account, though the company does not verify it) are prohibited from receiving direct messages from other users unless parents add those names to a friends list. Parents can set up additional controls, such as limiting the child to playing curated, pre-vetted games.

By sharing content via other parts of the gaming ecosystem, players exploit the fact that Roblox’s enforcement mechanisms end at its own platform.

Roblox enforces these rules vigorously, censoring in-game chats with software filters, watching player activity with the help of AI, and responding to problems with a battalion of more than 1,600 human content moderators, 24/7. Law enforcement agencies have held up the platform’s multilayered approach to security as a gold standard. “Roblox is very much an industry leader,” says Steven Grocki, chief of the Child Exploitation and Obscenity Section at the U.S. Department of Justice.

Yet for years, the company has quietly waged a technological shadow war against some of its own young users. These players have exploited Roblox to allow them to curse, upload explicit content, and manipulate games in ways the company never intended. And by sharing content via other parts of the gaming ecosystem—most notably Discord, which allows users to talk to one another via text, voice, and video, either one-on-one or in groups—they exploit the fact that Roblox’s enforcement mechanisms end at its own platform. It’s a shortcoming that can leave Roblox users far less protected than their parents might think. (Roblox says it works “diligently with other chat, social media, and User Generated Content platforms to report bad actors and content,” though it’s up to these platforms to take “appropriate action.”)

“This is an adversarial kind of situation . . . [and] we know that the bad actors are not going to stop,” says a top Roblox safety representative, who requested that his name be withheld.

[Video: Fast Company]The cat-and-mouse skirmishes between Roblox and its rebellious players take place daily and around the clock. The same morning that the Haha house went live, Roblox shut it down. But that hardly mattered: Two other condo games were still running, one set in a windowless bunker with posters of Bart Simpson and SpongeBob, another in a cavernous, smoke-filled nightclub. When Roblox shut those down, still others sprouted up. Nothing on Roblox indicates when a new condo game might appear, or what it might be called (“GAMEGAMEGAM,” “SCAR OF$”). Yet the revelers find them, their avatars often dropping in mere seconds after games go live. Before long, a popular condo game may have upwards of 1,000 players—all drinking, vaping, swearing, and generally getting their blocky freak on.

Their sudden appearance isn’t magic. The constellation of gamers’ favorite websites points the way. And these sites each have their own content standards. Roblox censors the word “condo,” but Reddit’s gamer groups can easily discuss these kinds of games. YouTube requires videos that depict the games’ most explicit moments to carry an age restriction, but it allows anyone to watch videos that explain how to find condo games. Discord is most helpful: Fast Company easily located some 150 Discord groups (also called “servers”) that are devoted to explicit Roblox content.

These servers—a couple of which have more than 10,000 users each—are home to roving camps of Roblox’s “bad actors”: the game-exploiters, the content-bypassers, and the condo creators themselves. They use Discord groups to mingle, boast about their exploits, share links to new condo games, and chat amongst themselves while in the game. Discord doesn’t prohibit linking to Roblox sex games, but says that all adult content must be relegated to channels and servers explicitly marked for ages 18 and older. In a statement, the company said that it “takes immediate action” if it finds out that users have lied about their age. (Discord doesn’t verify users’ ages at sign-up.)

These gamers, who spoke with Fast Company via Discord’s text and voice chat over a period of four weeks, describe themselves as longtime Roblox players who got into condos for the thrills, status, and money involved: Hacking a big platform and outwitting the Roblox commissars is an exciting challenge, they say, and there can be tidy business in selling in-game administrative privileges, which allow a player to fly and teleport, manipulate other users’ avatars, or even kick out other players.

Reviewing the chat-logs of these condo servers—Fast Company extracted and examined the logs from 31 of them, a stream of gamerchat that would run over 910,000 pages if printed out in six-point font—painted a picture of unsupervised adolescence in the age of massive online games. These appear to be kids with one foot still planted in Roblox, the digital playspace of their childhood, and the other extended to Discord’s more brazenly adult world. The all-lowercase text conversations reek of classic teenage boredom, a state made all the worse by COVID-19’s shelter-in-place orders. “I’d rather be outside hanging with my friends or something,” one condo owner said.

The burden of protecting one another in these games and chats often falls on the teens’ shoulders.

Yet these germ-free virtual spaces are hardly safe, even when the danger is difficult to discern. Some condo-themed Discord servers advertise themselves as inclusive and friendly. Other servers are riddled with racial slurs and hate speech; one Discord server devoted to Roblox condo games had a very active user with the username “WhiteSupremacist004.”

The world of condo games is a place where kids act like adults, adults may be posing as kids, and parents seem to be completely absent. Meanwhile the grown-ups who do have a vantage point into what’s going on—those running Roblox and Discord—seem incapable of fully shutting down this content and unwilling to publicly share all that they know. As a result, the burden of protecting one another in these games and chats often falls on the teens’ shoulders.

For K., the journey into condos began when he couldn’t find players for his G-rated Roblox games.

The 16-year-old struggled for nearly three years—his entire postpubescent life, basically—to make a hit game, but never managed to stand out from the tens of thousands of new games that are uploaded to Roblox every day. So this summer, he paid 1,000 Robux, or around $10, to a guy he’d met on Discord, who sent him the complete code for a condo game, which would allow K. to replicate it (with a few tweaks) each time Roblox’s content moderators shut it down. As Roblox investments went, K. felt it was a sure bet. “I’m like, I want to be rich on Roblox, too,” he said, referencing players he’d met with fat Robux accounts and virtual items galore. Then he created his own Discord server and got to work.

Like most Discord condo servers, K.’s functioned like an airport lounge, keeping members occupied and happy while they awaited the next game. In a dedicated channel that he named #condo-uploads, condo game links arrived as he uploaded them and departed as Roblox shut them down. Users could shoot the breeze in the #general chat, or hop on the #NSFW channels, which housed a near-constant stream of obscene photos and animated gifs. (Larger servers sometimes dedicate boutique channels to other black-market specialties in the Roblox underworld: game cheats, explicit music hacks, homemade Roblox porn).

Speaking to Fast Company after five days on the job, K. said he felt as though he had the basics down: He and a couple friends generated a bunch of throwaway Roblox accounts, fired up a VPN to mask their traffic, and uploaded game after game from their burner accounts. He made money, he said, by selling virtual t-shirts through a different Roblox account. When players showed up in his condo game wearing one of these shirts, K. would grant them administrative privileges. He managed to make nearly 3,000 Robux, he says, money which he spent entirely on Roblox items. But a week later, K. was knocked out of the condo racket: Roblox had identified his computer’s device ID and “hardware-blocked” him.

Few of the condo operators Fast Company spoke with admit to visiting their own games. That might get them a reputation as an “ODer,” a derogatory term meaning “online dater.” One owner, who says he is 17 and has been running a condo server for over two years, did cop to playing his games, but sniffs at calling them condos. He says he caters to a more mature, exclusive userbase; he prefers the term “ERP,” which stands for “erotic role-play.”

It’s exactly this combination—the perception of adult freedoms mixed with graphic, emotionless sex—that’s worrisome.

With all respect to the clientele of maison ERP, there’s nothing remotely erotic about these games. The digital gyrations are ridiculous, if impossible to unsee: thong-clad Roblox avatars twerking on stripper poles; beefy blond avatars buck naked except for COVID masks (written on the walls in this particular game: “#stayathomehub”), and enough crudely animated contortions to fill several volumes of the Kama Sutra (should Lego ever decide to publish an edition).

Judging by the in-game comments, most Roblox players find Condo games gross, at least when they first encounter them. (“EEEEWWWW,” wrote one player, upon arriving in a condo game in May.) But they also find them liberating—the digital equivalent of an empty house where the parents are out of town. “tbh ill probably only come here to swear,” chatted one user in a condo game in May. “fuck dat sex shit im here for the bad words.”

It’s exactly this combination—the perception of adult freedoms mixed with graphic, emotionless sex—that’s worrisome. Two experts on child predators who reviewed footage from condo games declared that they presented textbook terrain for predators looking to groom children for sexual abuse: “For somebody who wants to [prey on children], these types of environments make it very easy for them,” says Elizabeth Jeglic, a psychology professor who researches sexual violence at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City. The games’ cheerful, colorful settings makes them all the more insidious.

But not all condo operators are committed to safeguarding their users. Three essentially shrugged when asked what precautions they take (“I can’t tell if [players] lie about their age,” said one. “I just don’t care,” said another. “If horny little kids get catfished by pedophiles on condos then sorry this is becoming natural selection,” chatted another user in a condo server in April.) Y., a condo owner who claims to be 15 and operates a Discord server with more than 3,500 members, said he actually profits from predatory activity by soliciting sexualized photos from female users he meets on Discord and packaging those photos for interested buyers. (Fast Company reported Y.’s account of this activity to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children.)

Y., a condo owner who claims to be 15, said he actually profits from predatory activity by soliciting sexualized photos from female users he meets on Discord.

It’s difficult to track the real extent of criminal activity in the Roblox underworld. Teenage gamers and hackers sometimes say reprehensible things ironically to get a rise out of others—a practice known as edgelord humor. Case in point: Users call one another pedophiles almost as a running joke, a way to make light of the fact that they’ve transformed a kids game into an explicit sex party. The word “pedo” popped up more than 3,400 times in the 31 condo servers that Fast Company evaluated; spot checks of a few hundred instances of the word indicated that all but a small minority of references appeared to be in jest. “Teenage hackers are basically the least trustworthy group of people around,” says Quinn Wilton, the software safety consultant.

Meanwhile, the larger the Discord servers get, the more chaotic they become. Y. says he’s constantly on the lookout for violent and illegal content on his condo server. This is partly for self-preservation: If a server owner fails to remove egregious content posted by members (e.g. sadistic gore, animal cruelty, sexualized imagery of minors, threats of violence), Discord will shut the server down. So far, he says he’s banned users for posting exceedingly graphic content, which included videos and gifs of murders, genital amputations, and rape. (In a statement, a Discord spokesperson said: “We have a zero-tolerance policy for any illegal activity and work closely with authorities to keep our users safe.”)

He says he considered reporting these users to Discord as well, but that would have meant submitting a paper trail documenting their bad behavior, requiring him to spend more time with the content than he wanted. (Discord provides server operators with a default content filter that automatically detects and deletes inappropriate material, though owners can turn it off.) “i seen a lot,” Y. said via a Discord chat. “Ppl at my school are like innocent to me. I seen too much.”

Condo games make up a tiny proportion of the games available on Roblox, and they are nowhere near as popular as the platform’s hit titles, such as “Piggy,” which has been visited nearly five billion times since it debuted in January. A typical condo game is lucky to get a thousand visits, according to four condo game owners Fast Company interviewed. And these games aren’t easy for the casual Roblox user to find. Young gamers who chat only with their friends on Roblox are unlikely to stumble onto a condo game link. But kids do play these games—and there’s no reliable way of knowing whom they’re interacting with.

Roblox says it’s deeply committed to fighting bad actors on its platform: “We have no tolerance for content or behavior that violates our community rules and work tirelessly and relentlessly to create a safe, civil and diverse community,” a top safety representative said in an e-mailed statement. In addition to its longstanding content-moderation efforts, the company also recently partnered with Microsoft on Project Artemis to develop a set of tools that identifies and filters grooming patterns in chat to prevent online child exploitation. But Roblox hasn’t taken more structural steps to police its content and protect its users, such as limiting the ease of creating accounts, implementing a review system for games akin to Apple’s App Store, or allowing only trusted developers to upload games. Such solutions would be costly and could curb Roblox’s explosive growth.

In the meantime, the company won’t share the details of what its moderation team actually finds. Roblox declined to say when it first became aware of condo games, or how many condo games it has shut down. It won’t say how much money these games have netted both players and the company. Nor does it share the kind of aggregate statistics that YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, and even Discord now routinely provide in transparency reports, such as the number of user complaints of inappropriate content and requests for user information from law enforcement. Problems are minimal, the company vows—”a 0.1% problem . . . [caused by] a very small, vanishingly small minority of people on the platform,” says the Robox safety representative who declined to be named.

Some of the only data available comes from the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC), which lists the number of referrals its CyberTipLine has received from tech companies—reports that may involve anything from child sex trafficking to suspected online enticement of children, and which are submitted by the companies themselves. In 2019, Roblox sent 675 reports to NCMEC. The company says it reports any suspected child exploitation, abuse materials, or online grooming. Discord submitted 19,480 reports to the center. (By comparison, Facebook submitted 15.8 million reports and Google referred 450,000.)

Opacity, it turns out, is an industry-wide problem. No major gaming companies or massive online gaming platforms issue transparency reports or share data about enforcement activity. (Microsoft provides the number of user reports and law enforcement requests it receives related to Xbox and OneDrive, for example, but it doesn’t offer similar insight into Minecraft.) Meanwhile, the gaming industry’s parental guidance rating system (akin to the Motion Picture Association’s PG and R ratings for movies) evaluates games based on the content created by the companies themselves. It doesn’t review the risks posed by other players: It simply tags all multiplayer titles with a boilerplate “Users Interact” notice. As a result, Roblox’s “E10+: Appropriate For Everyone 10 and up” rating hasn’t been affected by condo games.

As kids collectively spend billions of hours playing these games, the public has little insight into what’s actually taking place inside them, or what the game companies are doing to protect them.

Yet these games are increasingly powerful content platforms—”a new category of human co-experience,” as Baszucki says—and they are populated by children. Anecdotally, players say they regularly hear racial slurs, hate speech, and bullying language in games of all kinds. And in Roblox, they’re able to enter environments that are far more mature than many people realize. As kids collectively spend billions of hours playing these games, the public has little insight into what’s actually taking place inside them, or what the game companies are doing to protect them.

Members of Congress are pushing the government to do a better job of safeguarding kids across the Internet. In March, Senators Lindsey Graham and Richard Blumenthal introduced EARN IT, a bill that would make tech companies more liable for child abuse imagery trafficked on their sites and create a commission in charge of developing voluntary guidelines around child safety and transparency. In May, Senators Ron Wyden, Kirsten Gillibrand, Bob Casey, and Sherrod Brown introduced another bill that would allot $5 billion to crack down on child sexual abuse material online over the next 10 years. Yet lawmakers have yet to focus their efforts on protecting children as they play these massive online games. (Steven Grocki, who oversees child exploitation at the U.S. Department of Justice, had not heard of Roblox condo games until Fast Company reached out.)

[Video: Fast Company]With little oversight, that leaves the work of spotlighting in-game crime to natives like Dazzely. But in recent weeks Roblox has made that more difficult. On July 28, the company banned his main Roblox account and blocked his computer’s hardware ID, effectively shutting him out of the game. On July 31, the company went after his YouTube channel, blanketing his recent videos with copyright violation notices, which prompted YouTube’s content moderation system to deactivate 14 of them. Roblox even filed a copyright violation notice against a video where Dazzely discusses the company’s efforts to shut him down. He’s since delisted most of his videos or made them private.

Ironically, Dazzely had already been planning to leave condos behind. Roblox had gotten much better at its condo game whack-a-mole, he observed in an earlier interview. And the games he did manage to visit seemed nearly identical to the ones that came before. For a muckraker like him, it had become tedious.

But Dazzely has no intention of leaving Roblox completely behind. He knows there’s no shortage of other kinds of darkness and skullduggery on the platform. A couple months ago, he paid a visit to ePal.gg, a site started in January that contains more than 40,000 profiles of people advertising themselves as “e-Girls” and “e-Boys”—flirty in-game escorts whom customers can pay to play with online. The four Pal founders say that they require all their ePals to be over the age of 18 and prohibit sexual harassment. But they acknowledged that they don’t check ages and that they have just four employees reviewing applications. Recently, the third-most watched video in ePal’s content section was “How to Seduce an e-Girl.” For Dazzely’s YouTube dispatch, he hired an e-girl who said she was just 17. (They played Roblox volleyball together with some of his fans.)

In his real life, Dazzely’s turning his attention to college—he’d eventually like to become a history teacher. But for now, he wants the underbelly of Roblox to remain his creative focus—if he’s ever allowed back in the game. “You can do so many things on Roblox. That’s why I’m not bored of it,” he says. Maybe someday he’ll leave his digital playground for the “real world.” On the other hand, he muses, maybe older folks will finally realize that they’re one and the same.

Technical assistance provided by Ken Ficara and Natalie Soler. Data analysis software was provided for this story by the Everlaw for Good program.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.