It’s been 30 years since the Americans with Disabilities Act was signed into law. A landmark piece of civil rights legislation, the ADA prohibits discrimination against people with disabilities and mandates the removal of barriers to equal participation in public life. Those barriers are often physical—buildings only accessible by stairs, crosswalks unsafe for those with low or no vision, steeply sloped walkways that put wheelchair users at risk. Getting rid of these physical barriers lies at the heart of the ADA’s intentions.

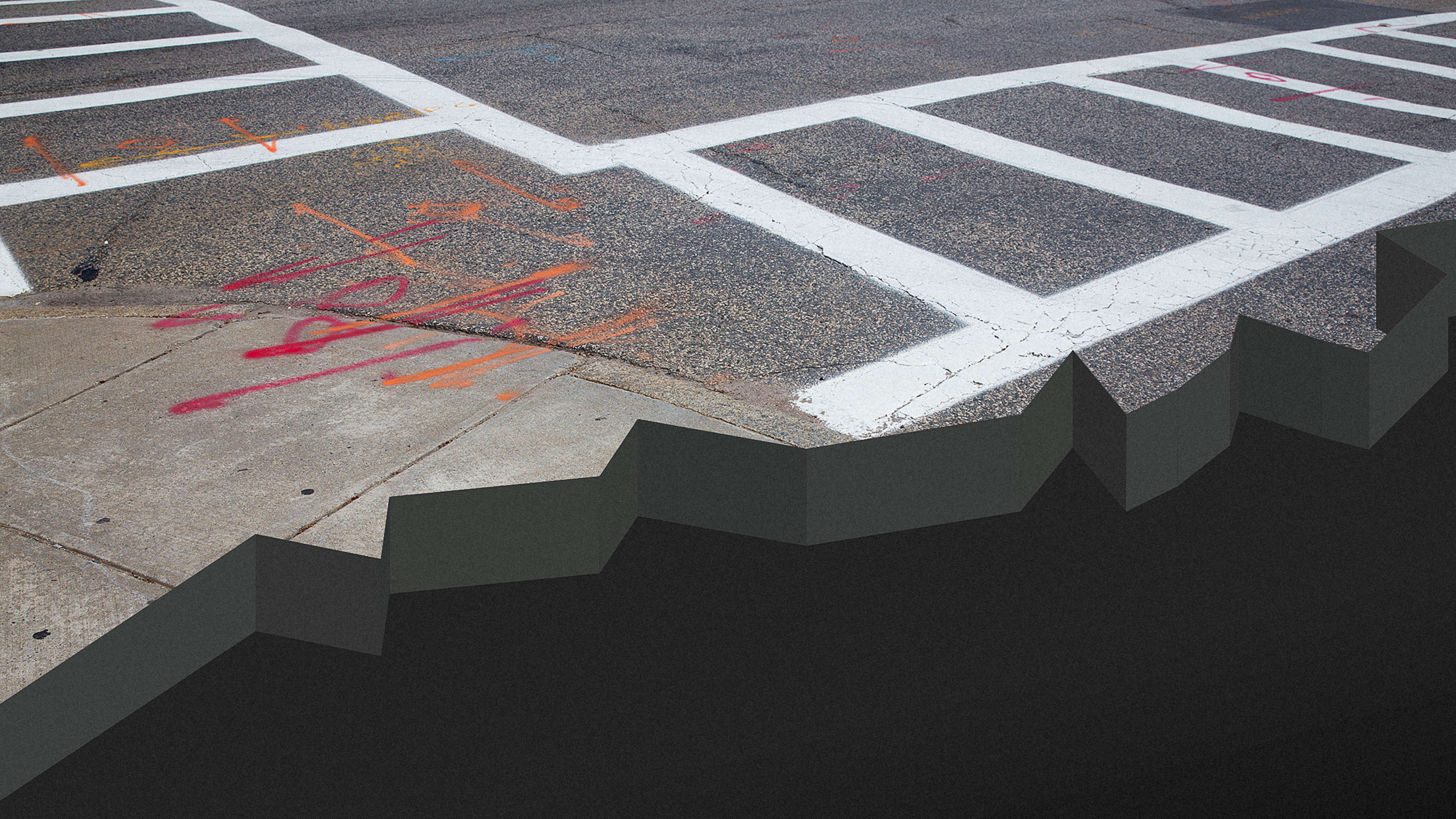

But after three decades, the barriers remain widespread. This is especially true on the sidewalks, crosswalks, roadsides, and curbs of the American public right-of-way. According to a new study, 65% of curb ramps and 48% of sidewalks are not accessible for people with disabilities.

While these numbers represent stark inequities for people with ambulatory and visual disabilities, inaccessible transportation infrastructure affects a wider range of people. It’s estimated that one in seven adults in the United States has a mobility-related disability, and roughly a quarter of adults experience a significant disability at some point in life. Better infrastructure and more easily accessible sidewalks are also good for pregnant women, parents with young children, older people with limited mobility, and really any pedestrian who wants to safely move amid what is often a disproportionately car-oriented urban realm.

Cities are far behind where they should be, according to Yochai Eisenberg, a professor of disability and human development at the University of Illinois at Chicago. He’s part of a team at the Great Lakes ADA Center that conducted the study by looking at ADA transition plans, the documents that states and local governments are required by the federal government to have in order to outline the work they will do to reduce such barriers. The plans reveal “what percentage of the sidewalks are compliant and what are not,” Eisenberg says. “They’re an important tool for understanding where we’re at in terms of an accessible city in relation to the pedestrian environment.”

But, despite the federal requirement in place since the passage of the ADA, many cities haven’t even made these plans. Of 401 government entities reviewed as part of the study, only 13% had transition plans readily available. Eisenberg says participation has been low among local governments because only a few states have actively enforced the requirement or set consequences for not complying. Many places have taken a piecemeal approach to ADA compliance, upgrading their infrastructure to ADA standards only when maintenance or new construction is necessary.

But this is starting to change, Eisenberg says. Beginning in 2015, the federal government established a working group focused on ADA transition plans and began pushing states to complete their plans, and to get the local governments under their umbrella to do the same. The most successful efforts have been in states that required plans in order to qualify for state funding for transportation projects such as road repairs and transit operations. “Some states like Indiana really mandated it—if you want funding you need one of these. And other states didn’t,” Eisenberg says.

Most of the plans now in existence came about over the past five years, Eisenberg says. This is partly due to pressure from the federal government, but also from another more common avenue of ADA compliance: lawsuits.

“What you see is different local governments being sued,” Eisenberg says. “And so the ones that are making the plans are the ones that are nearby those that got sued, because they say, well, we don’t want to be the one who gets sued next.”

Not all governments are waiting until they’re forced to act. Eisenberg says there are a number of city governments that have done a good job of making ADA transition plans and then actually following through and making the physical improvements. He points to the city of Tempe, Arizona, which has set a goal of addressing barriers to accessibility by 2030. The city has created an online map showing where the plan will roll out first, and details such as curb ramps that will be replaced and sidewalk sections with noncompliant slopes. Depending on the project, the funding for these upgrades will come from local, state, or federal transportation sources.

The city has also been active in involving the public in the process, which Eisenberg says should become a model for others to follow. “Cities that engage their public, get them really involved, and prioritize the places that the people in the community want to be accessible— those governments are going to be most successful,” he says.

Despite the low percentage of sidewalks and curbs that meet accessibility requirements, Eisenberg says the growing number of ADA transition plans is a hopeful sign that things are improving, albeit slowly. “That at least gets things started. Does that mean that those places are implementing more infrastructure? I’m not sure. It’s one of the things we’re trying to research,” he says. “But I think at least they know where the problems are and can focus on certain areas.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the final deadline, June 7.

Sign up for Brands That Matter notifications here.