As of the end of June, there were more than 10.4 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 worldwide. The real number, of course, is much higher, though unknown, because of limited tests and because of how many people who are infected never have symptoms and so never think to get a test. At the nonprofit Chan Zuckerberg Biohub, researchers are using changes in the virus genome to estimate the number of undetected infections—and found that in some areas, more than 90% of cases weren’t discovered.

In a new paper, not yet peer-reviewed, the researchers estimated the numbers of infected people in 12 locations in Europe, China, and the U.S., along with the probability of case detection over time and how long it took to detect an outbreak in a given area. As the virus began to spread in each location, the majority of infections—more than 98%—were undetected in the first few weeks. While that number went down as testing increased, the researchers estimated that in Shanghai, for instance, 92% of infections—or 3,900 cases—were never detected over a nearly two-month period.

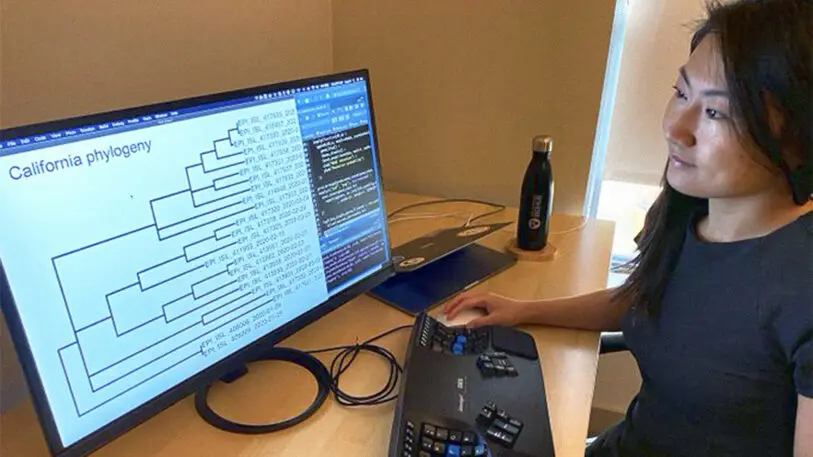

By studying the virus genome, it’s possible to estimate infections across a population even when large-scale testing isn’t happening. “The virus genome mutates at a fairly constant rate as it spreads through the population,” says Lucy Li, the data scientist at the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub who led the study. “For example, if we know that one mutation occurs every three transmissions, and we see that on average, there are two mutations between confirmed cases, then that suggests around one in six infections are detected.” The study’s methods, she says, were more complex, looking at factors like randomness in mutation and variations in how infectious people are. Using genetic data that labs share in a global database, the researchers used a mathematical model to run an analysis of the mutations.

Looking at data ending in early April, the researchers found that Shanghai had the largest number of undetected cases. In other locations, the estimate was lower, but that may have been because of what stage the outbreak was in at the time the data was collected. They estimated that New York, for example, had only 13% undetected infections (that analysis might change with more data).

“There are many factors that could explain the differences between locations: different demographics of people who have different rates of becoming symptomatic, sub-populations who have less access to testing facilities, availability of testing,” Li says. “Furthermore, as this analysis was carried out during the early stages of the epidemic in the U.S., New York, like other U.S. states, had relatively few available viral genomes. This means the relatively low estimate of undetected infections in New York could be due to a delay in available genomes.”

Other studies have also suggested that large numbers of people aren’t being diagnosed. A recent study published in Science Translational Medicine looked at the number of Americans who went to the doctor with flu-like illnesses in March but weren’t diagnosed with the flu—and weren’t tested for the new coronavirus because testing was so limited. There was a spike in doctor visits at the time. Based on the data, along with extrapolations about people who were likely sick but never went to the doctor, the study estimated that as many as 8.7 million Americans were infected with COVID-19 at the time, but fewer than 20% were diagnosed.

Although COVID-19 testing rates are growing in the U.S.—with around half a million tests a day now—the country still isn’t testing at the level that many epidemiologists recommend (and much less than the 5 million a day Trump promised in April). Li says that though more tests are needed, it’s also critical to test strategically to find people who aren’t experiencing symptoms. “Given that the majority of the population still has not been infected, random testing is not the most efficient at finding asymptomatic infections because most tests would still return negative,” she says. “More intensive test-and-trace efforts would help focus testing efforts to those who have known exposures and increase the likelihood of finding previously undetected infections.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.