It’s safe to say that 2020 has been a year of unpredictability and adaptation. The two go hand in hand, of course. The unpredictability of the COVID-19 pandemic has forced businesses and individuals to adapt to protect everything from the economy to our very lives. The technology industry, too, hasn’t been exempt from this adaptation–not even the most valuable tech company on the planet.

Today, Apple held the keynote for its first-ever online-only Worldwide Developers Conference, which runs all week. The reason Apple had to scrap the conference’s in-person element goes without saying. But despite the platform change, the fact that Apple is holding a WWDC at all this year brings much-needed normalcy to a world that currently has a dearth of it.

And it’s thanks to that platform change that, just as in past years, we now know many of the cool things Apple has in store for us when the next major iterations of its operating systems, including iOS, iPadOS, and MacOS, drop this fall. But for me, the most important of today’s announcements relate to upcoming privacy enhancements, though they were just a small part of a packed keynote. After all, while a Mac that runs on a new chip has its benefits, they pale in comparison to technological advancements that protect our human right to privacy every day.

Now that’s a bold statement. Federighi makes a strong case for it, and not just by detailing Apple’s upcoming privacy enhancements. During our conversation, he delved deep into the company’s history with privacy. He even looked centuries into its future, revealing what he believes will be one of the company’s most important lasting legacies.

Apple circa the year 2300

Right now, most of us are worried about what life will be like just months from now. But as the Apple executive in charge of iOS and MacOS development, Federighi needs to consider timelines that stretch beyond months or even years.

Though not yet a household name like Steve Jobs or Tim Cook, Federighi is one of Apple’s key execs. Besides his duties as software chief, his importance is also evidenced by him being one of the most frequent faces seen introducing new Apple tech at the company’s launch events (hint: he’s the funny one). He didn’t just preside over much of this year’s virtual keynote—he dominated it as a presence, far more than Cook.

But is Federighi really thinking centuries into the future? Not in terms of product development. But when it comes to Apple’s lasting legacy, the answer is a resounding yes.

When Apple was founded, the proposition was, ‘This is the personal computer. This is your own data.’”

That’s a fantastic marketing line. And Apple has been trumpeting its privacy stance in recent years to great effect, as people finally wake up to the fact that their privacy is eroding all around them as everyone from tech giants to governments wants us to have less of it.

But is Apple’s pro-privacy stance little more than Apple giving consumers what they seem to want, like some kind of dog chasing the societal zeitgeist? Not according to Federighi. “People sometimes consider, more recently, privacy as a kind of genius marketing strategy for Apple,” he says. “Or years before, it was thought of as some bizarre fixation of ours that no one kind of got. The truth is privacy has been foundational to this company and how those of us who work here think about what we do, truly going back to the origin of the company.”

To support his point, Federighi gives the example of one of Apple’s most important products of all time. No, not the iPhone or iMac. It’s something the company released decades earlier, in 1977–the Apple II.

“When Apple was founded, the proposition was, ‘This is the personal computer. This is your own data. That set of floppy disks that you have in the shoebox next to your Apple II–that’s yours. It’s not on the mainframe. It’s not on the timesharing system–it’s your data,'” Federighi says. “And people at Apple, as the world has evolved, have continued to think of this as personal computing. And that the data that you create, the things you do with your computer–those are yours and should be under your control. You should be aware of what’s happening with your data.”

Which brings us to today’s announcements.

Privacy through transparency

To ensure that the Apple of today builds that privacy legacy of the future, the company for years has been guided by four core principles when it comes to giving users more privacy (or, as it’s known by that other “p”-word, power).

Those four principles are data minimization, in which Apple collects as little data about users as possible to deliver its services. On-device intelligence, which is a fancy way of saying that your iPhone is powerful enough to crunch the data you give it without needing to upload that data (such as your photos) to a remote server to be analyzed. Security, which naturally means that the data on your phone is kept safe from attacks. And transparency and control, a principle that’s especially apparent in WWDC’s announcements.

As Federighi notes, transparency and control mean Apple aims to give users the ability to see and control what data of theirs is being accessed by the company and third-party apps. If you’ve ever looked in the iPhone’s Settings app under the “Privacy” section and seen the lists of apps that have switches next to their names, that’s an example of this principle in action. Those switches enable users to allow or deny access to things like the iPhone’s camera, for example.

If third parties have access to your location data, they can extrapolate all kinds of personal information about you—information you may not want them to have: things like your religion (Does she go to a church, mosque, or temple?), your health (Why is he at this cancer clinic?), and even your sexuality (This person sure seems to frequent certain types of bars).

Of course, giving apps access to our location data also provides us with a ton of benefits–everything from real-time driving directions to neighborhood restaurant recommendations to local weather forecasts.

Before Apple’s “Approximate Location” feature, you had to choose between giving apps wholesale access to your exact location, which enables all those cool features, or no location at all, which cuts you off from them. You did this by granting your precise location data to apps “always,” “just once,” or “never.” And unless you denied an app permission, it got access to your exact location for as long as you allowed.

But many apps that use location to provide services–such as weather apps and local news apps–don’t need to know your exact location. Instead, all they need is a general idea of where you are. And with iOS 14 and iPadOS 14, Apple will allow you to grant apps your approximate location only.

With this option, an app will never know the precise spot you’re at. Instead, it will learn the general area, which is often enough to provide the same level of service without intruding on your privacy to the same degree. To achieve the “approximate location” feature, Apple divided the entire planet into regions roughly 10 square miles in size. Each region has its own name and boundaries, and the area of the region is not based on a radius from the user–it’s fixed. That means that an app can’t extrapolate your precise location from approximate location data, because you aren’t necessarily at the center point of that approximate location boundary.

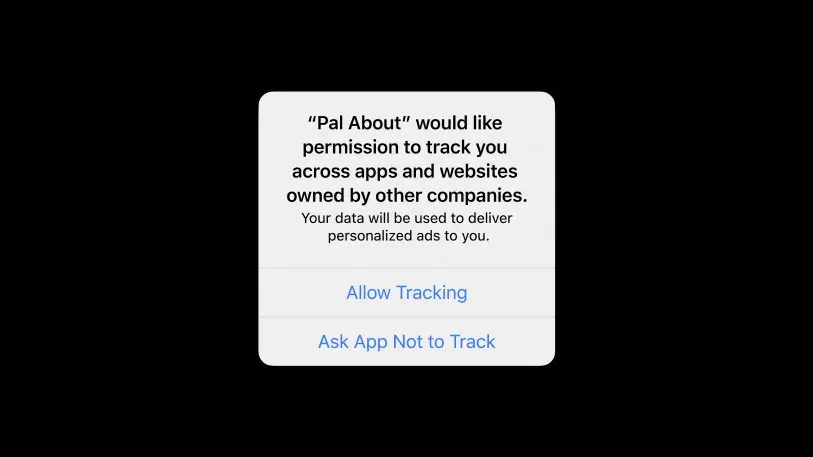

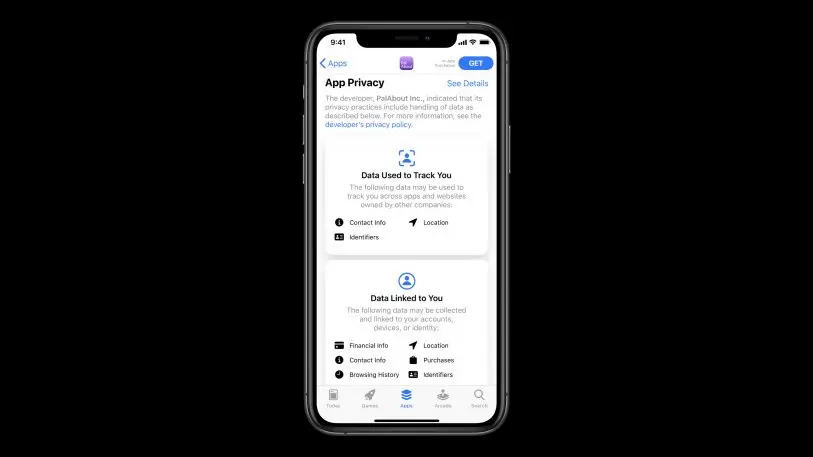

Cross-tracking is a tool advertisers and data brokers often use to glean more information about people, particularly in ad-supported apps. Code in these apps and their ads allow advertisers and data brokers to follow you as you jump between apps by assigning you a unique identifier. This identifier lets an advertiser build up a profile around you and target you across a range of apps that you use. But, thanks to these new app-tracking controls, users will now be able to see what apps they’ve granted permission to cross-track them and revoke that permission at any time. This applies to Apple’s own apps as well.

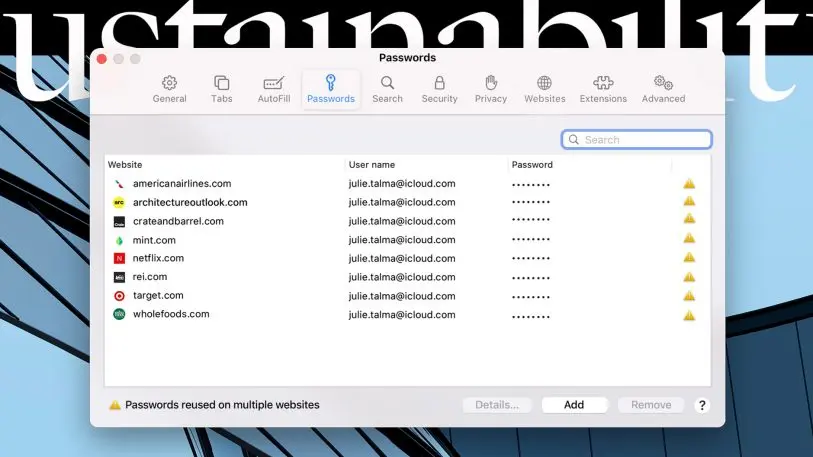

An additional subtle transparency-and-control privacy enhancement for iOS and MacOS: apps will no longer have blanket access to the pasteboard (aka the clipboard). That’s the part of the OS that stores the data you’ve copied to paste in another location. Previously, most apps could access the last data you copied without you ever knowing it and whether or not you copied the selected data in their app.

The issue is that a nefarious app could steal sensitive data you had copied and pasted—for instance, your social security number or other personal information. Though there isn’t a lot of evidence apps have done this on a wide scale, apps will now require your approval to access the pasteboard for the first time. If a messaging app requests approval, it’s probably legit–but look out if, say, a free gaming app wants to get at your pasteboard.

Listening to users

Not even a company that wants privacy to be one of its lasting legacies can deliver perfect privacy. Rather, it’s a constant battle, which means Apple has to choose which features to prioritize in any given year.

I ask Federighi how Apple goes about doing that. While he says that some of the privacy enhancements Apple revealed today were “years” in the making, he notes that others came about because customers emailed him and expressed their worries.

For example, another new privacy feature coming to iOS 14 and iPadOS 14 is system-wide camera and microphone notifications. These will be two indicator “lights” just above the cellular signal in the iPhone and iPad’s status bar. Previously, indicators only showed if you had activated the mic through an action, such as initiating a video call. These new indicators will ensure that you will know if any app is using or has recently used your camera or mic. If you see a green indicator light, an app is using your camera. If you see an orange indicator light, an app is accessing your microphone–even an app in the background.

That worry, though unfounded, feels legitimate to many people–especially if they don’t understand just how powerful and far-reaching the algorithms tracking us can be even without audio being involved.

“Now, in many cases, this, in fact, was not happening,” says Federighi of concerns over iPhone users being unwittingly recorded. “We know it was not happening. But they believe it is. And so, providing that peace of mind through a recording indicator that will always let you know whether an app, at that moment, is accessing your camera or accessing your microphone is important.” He cites this as an example of how Apple tries to stay “ahead of something that is emerging and provide a great solution before it can become a problem for our customers.”

But while customers and privacy advocates always appreciate Apple’s privacy enhancements, I ask him how developers react. After all, when Apple implements a new privacy feature, it has the potential to disrupt apps that end up with less unfettered access to a platform.

Imagine a world where Apple did not protect the privacy and security of our platform, and people felt skittish about doing anything with their phones.”

“You know, imagine a world where Apple did not protect the privacy and security of our platform, and people felt skittish about doing anything with their phones,” he adds. “Well, that would be really bad for developers in general. And so, I think our ecosystem [of developers] generally appreciates that we create this very trusted platform, and then we all get to offer services to users in the context where the user has a foundational trust.”

Apple’s increasing privacy controls are commendable. But is it realistic to hope, as Federighi says he does, that customer demand for Apple-like privacy innovations will spur the tech industry as a whole to move in that direction? I wanted to ask him this because many people, rightfully, point out (me included) that Apple can afford to offer privacy to its users because the company bases its primary business model around selling very high-margin devices. Other tech giants, such as Google and Facebook, make their billions by leveraging user data to target advertising. Much of this happens on Apple’s platforms–and Google even pays Apple for the privilege of being the default search engine on its hardware.

But while Federighi didn’t address Google’s and Facebook’s revenue streams directly, he disagrees that it’s pointless to hope for a more significant sea change surrounding privacy from the rest of the tech industry.

“I think that there are many instances where we started providing privacy protections of some sort, and then we then saw others in the industry–some of whom have different business models than we do–adopt those practices because users came to expect them,” he says. “That’s happening all over the place. I mean, look at whether it’s apps protecting customer messaging with end-to-end encryption. Or some of the kinds of location protections we’re talking about. Or some of our protections, like requiring apps to ask before they access your photo libraries, and so forth. You see those protections being added to other operating systems, inspired by our work and based on the fact that users demand them.”

Federighi also thinks that that impact isn’t limited to others merely copying Apple’s privacy controls. He says that the company’s influence on the industry might change the business models of other companies. An example he gives is a developer who might have previously monetized a free app through selling user information to data brokers. As people become more aware of the importance of privacy–and demand it–that developer could potentially make even more profit from users who are willing, if not eager, to pay for a service with, you know, cash.

“I believe we will influence the industry in a positive direction in those ways,” Federighi says. However, it also should be noted that developers occasionally have public battles with Apple over how apps distributed on the company’s App Stores are allowed to charge users for their services. As WWDC approached, Apple insisted that Basecamp’s new Hey email app can’t sidestep iOS’s in-app purchase system—and Apple’s 30% revenue cut—by requiring subscribers to pay Basecamp directly. That raised the hackles not only of Basecamp’s founders but also other prominent developers before Apple approved an updated version of the app.

Dangers abound

At the beginning of our conversation, Federighi told me he believes Apple’s work on privacy will be one of the legacies the company is remembered for, even centuries from now. But ending our discussion, I ask him to give me his opinion on the privacy landscape in the nearer term: specifically, I ask him where the greatest threats to our privacy will come from in the next five years.

I list the three most common entities many researchers agree represent the greatest risks: the threat from businesses, such as tech giants; the threat from governments who are growing more aggressive in their calls to force companies to weaken encryption; and the threats from, well, the public–all the people out there who aren’t even aware of the dangers facing them and their data.

“I think the thing is, those are all actually connected,” Federighi says. “Because, to the extent that users don’t understand how their data is being used–that they’re contributing their data unknowingly to centralized data repositories–those, in turn, become areas open for abuse or unwarranted or unknown access.”

That’s what we’re going to keep trying to support–our customers being in control of their privacy.”

You can’t talk about privacy and authoritarian governments without mentioning China. American companies—IBM, Microsoft, and yes, Apple—frequently get called out because they are forced to operate within the legal constraints of that country’s system. But it’s important to note that because of one of Apple’s core privacy principles–data minimization–it’s able to provide its users everywhere with more privacy. Indeed, Federighi calls Apple’s “data minimization” principle its “foundational” privacy principle.

“We believe Apple should have as little data about our customers as possible,” Federighi told me. “And so we seek to gather as little data as possible to deliver [services], because we believe the mass centralization of data is inherently a risk to customer privacy. And so data we don’t have, data that no one else has, is data that can’t be breached or data that can’t be misused.”

It’s hard to think of another big tech company that could claim that. Yet it’s a statement that seems to hold up given how hard Apple works to increase data minimization year after year through features such as the new “Approximate Location” feature.

“I think the protections that we’re building in, to intimately say that the customer’s device is in service of the customer, not of another company or entity–the customer is the one who is in control of their data and their device–is what’s most compatible with human rights and the interest of society,” Federighi says. “And so that’s what we’re going to keep trying to support–our customers being in control of their privacy.”

And with iOS 14, iPadOS 14, and MacOS Big Sur this fall, Apple’s customers will be in control of their privacy more than ever before. They are controls born of Apple’s long history with privacy and are just the latest step in what the company hopes will be one of its lasting contributions to society.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.