The past week in America has been both gutting and revealing. It has laid bare a number of ugly truths that every corner of our society is now being forced to reckon with.

I am an African-American writer, strategist, and the president of a branding and technology studio. Professionally, that means I spend my time helping organizations tell their stories, understand their audience’s pain points, and consult with them on what relationship must be built, what pathways cleared, and what value must be exchanged before they can reasonably expect any meaningful or lasting change in their audience’s beliefs or behavior. I spend a lot of time asking a lot of questions like, What is the problem we’re solving? Are people even aware they have it? Once they are aware, what do people need to know and feel in order to take action? Most importantly, what specific actions are we asking them to take?

I am also an African American mother, wife, daughter, and sister, which means I am feeling the full weight of the moment we are in. It also means that unlike the branding, campaign, and consulting work I do in my professional career, my personal fate is directly tied to the change I am championing here.

For all of those reasons, but specifically as a Black leader in this industry, I feel qualified and compelled to share my perspective in this open letter.

I’ve seen a number of great posts about what white people can be doing, in general, to actively combat racism in America. Lists like this and this are so important and I’m grateful for their circulation. I think it’s also really important to talk about what we in this specific industry should be doing. It’s important to examine the power we have and our responsibility to wield it thoughtfully.

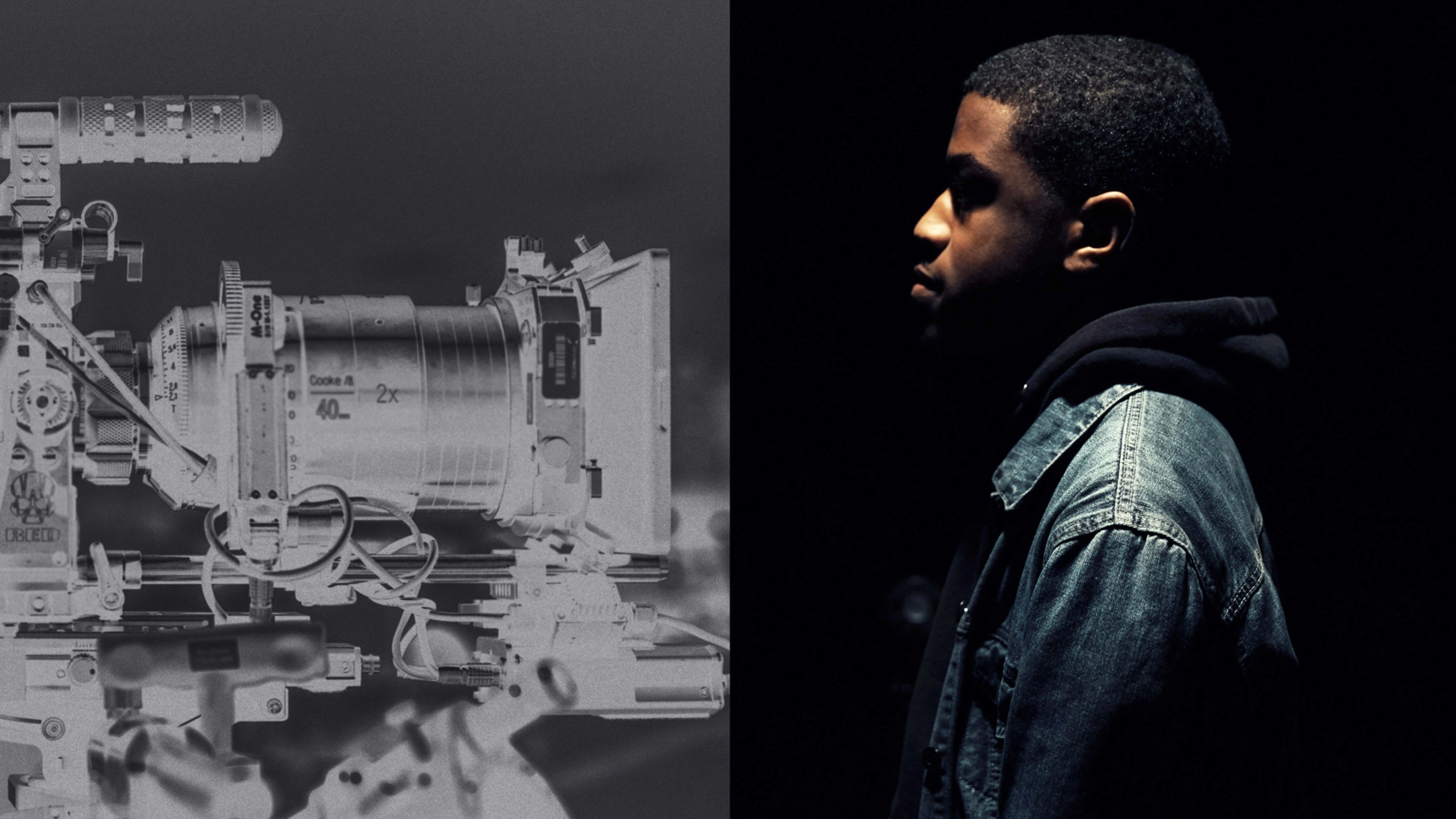

As image-makers, platform builders, conversation managers, and storytellers, we contribute to the images, messages, and perceptions that circulate within our society and culture. These images and messages have tremendous power. They have the power to influence the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors of our collective society today and for generations to come. They have the power to make people see and recognize the humanity in others, or the power to objectify and dehumanize others. They have the power to make people feel fearful of others, or the power to make them feel safe. They have the power to make people feel beautiful or ugly, seen or unseen, accepted or ostracized, revered or reviled. They have the power to celebrate our vulnerabilities, flaws, and imperfections, or to lull us into the false comfort and unattainable pursuit of perfectly curated, beautifully crafted lives and feeds. Most importantly, the words and images we create and choose to circulate create powerful mental associations that define how we perceive each other and the world around us.

We in the advertising, marketing, communications, media, and entertainment sectors are responsible for creating and circulating the very images that . . . influence whether someone lives or dies.”

“Perception acts as a lens through which we view reality. Our perceptions influence how we focus on, process, remember, interpret, understand, synthesize, decide about, and act on reality,” Jim Taylor, Ph.D., wrote in Psychology Today. “In doing so, our tendency is to assume that how we perceive reality is an accurate representation of what reality truly is.”

Perception affects whether you will be deemed a “good fit” for a job or pose “a threat” to police. Perception affects whether you are kindly offered a mask, or are harassed and beaten for not wearing one. Perception affects whether you are offered water and medical attention after being handcuffed or left to die under someone’s knee. Perception is a matter of life and death for Black people.

Police officers shoot unarmed Black men because they “feel afraid,” yet calmly de-escalate conflicts with fully armed white men because they “knew they didn’t pose a real threat.” People clutch their purses or reach for their wallets when they see a group of young Black boys walking toward them, but relax into memories of what it means to be young and carefree when a group of “clean-cut” white boys goofing off bumps into them. The feelings are often real in both cases. The questions to ask are, Why are you afraid? Why are you unafraid?

It all comes down to perception. Our perceptions are formed based on a combination of our real, lived experiences, and the images and stories we’ve been exposed to that fill in the rest. If you have no real lived personal experiences with Black people (at home, in your friend circles, or at work) to draw upon, then you’re left with the images depicted in the media, in film, television, and literature that you choose to consume. Conversely, if you have real, lived personal experiences with a diverse range of Black people, then it will effectively balance or check any media images that contradict those experiences.

Much has been written about media portrayals and the impact they have on public attitudes toward people of color, about the history of racial stereotypes and how these stereotypes were deliberately crafted and strategically used to reinforce white supremacy either by excluding or minimizing the contributions of people of color or by depicting them as violent, dangerous, simpleminded, greedy, untrustworthy, or lazy.

This collection of dehumanizing and objectifying stereotypes, and those that have followed, have dominated the mainstream cultural record of the lives and character of Black people for centuries. There is a long, painful account of the evil deeds and destruction that can be done to Black bodies with impunity when not seen as fully human.

Seventy-five percent of white Americans report having social networks comprised entirely of whites with no minority presence, according to a PRRI American Values Study. This lack of meaningful relationships with people of color means that the images that get circulated in media, TV, and film carry all the weight in developing the majority of white Americans’ perception of people of color. When those images are largely negative, diminutive or one-dimensional (because the people creating them are also drawing from limited meaningful experiences with people of color), a vicious cycle of stereotype-fueled perceptions is created and consumed, created, and consumed.

That’s where this community comes in.

We in the advertising, marketing, communications, media, and entertainment sectors are responsible for creating and circulating the very images that either contribute to or combat the perceptions that are conjured up in the mind of an officer during a split-second reactionary fear-based moment or in a cold-blooded, dehumanizing 8 minutes and 46 seconds. They influence whether someone lives or dies.

So what can the creative community, content producers, and leaders of agencies do with this power? What do we have the responsibility to do?

- Work to learn and understand the history and legacy of systemic racism in America.

- Work to learn and understand the history of racial stereotypes in America. If you are responsible for creating or distributing content in America, this is as important as mastering Sketch, landing sponsorships, perfecting your editorial calendar, or mastering Premiere Pro.

- Examine how these images have evolved but are still hard at work in our society and culture largely affecting how people of color are perceived today (see: Heineken, Volkswagen, Gucci, H&M, Abercrombie & Fitch, Pepsi, etc.)

- Follow and amplify the voices of people of color in our industry. Seek out designers, writers, technologists, strategists, content creators, and thought leaders. They are out there.

- Be intentional about hiring and building diverse teams. Not only is it essential to open up an industry that is overwhelmingly comprised of white people (which is a problem for all the aforementioned reasons), but because having these voices and perspectives in the room leads to better and more resonant, ideas, work, and work culture.

- Make a meaningful commitment to hiring diverse teams. Adding a token Black person to the team doesn’t check the box. Calling in that one Black person in your office to review the campaign at the last minute, after millions of dollars in media and production have already been spent, will not defend against these kinds of narratives from being perpetuated. When faced with the choice of speaking up and potentially risking their job (or future mobility within the company) or lightly objecting and then slowly receding out of the conversation while bad ideas get feverishly greenlit, a solo Black person may not have the financial luxury of making the noble choice. When entire teams are meaningfully diverse, people of color feel supported and protected, or at the very least respected, in their dissent, because they share a common experience of being marginalized or stereotyped. The burden of being the sole litmus test to police creative and “represent the race” is misguided, to begin with, but is also just too great to bear.

- Foster a culture where all employees feel safe and supported for calling out racist jokes, sentiments, or requests–whether made by a colleague, supervisor, or your largest client. Make it clear to your employees that their job is not on the line when being vocal about these insidious transgressions. On the contrary, publicly commend their actions as an example of your core values.

- Make it clear to your clients that while they pay you to produce work, you won’t compromise your values in order to be paid.

- Do the work to understand racially and culturally diverse audiences. Spend the time and effort to understand their diverse circumstances, interests, questions, and the context of their challenges in order to communicate with them in ways that are meaningful, relevant, affirming, respectful, and dignified.

- Source stock imagery or produce original content and cast talent that reflects the diversity of audiences. Understand that these images and narratives need to reflect the diversity within races, genders, and cultures, not just diversity among races, genders, and cultures.

- Diversify your sources of inspiration. As creatives, we need inspiration. Examine where you’re looking for it. Order magazine subscriptions, coffee table books, and artwork for your office that feature and are created by people of color. Seek out films and literature featuring Black actors, directors, and writers. Subscribe to podcasts published by communities different from your own, on topics that fall outside from your own world view. This will give you access and intimacy to issues and perspectives that you might not currently have in your personal, lived experience.

- Diversify your sources of knowledge. Invite speakers and thought leaders from a diverse set of backgrounds to advise, offer guidance, and share their subject matter expertise with you and your team.

- Create “Commitments to Action” for departments within your organization and make them public:

- Design — How, where, and what imagery do we source? Whose cultural frame of reference are we designing from? Whose tastes, needs, and problems are we solving for?

- Story/PR — What stories are we telling and from whose point of view?

- Strategy — What assumptions are we making about our audience? Do we know their true pain points? Have we sought their direct input?

- Production — Who are we casting to act, write, and direct? How are our requirements for these roles serving to dismantle or perpetuate negative racial stereotypes?

- Executives — How is race factoring into who we are hiring, firing, recognizing, and promoting? Are we creating a culture that values independent thinking, encourages people to speak up against Racism and racial stereotypes, and expects our work to reflect racial diversity?

- I want to be clear. This is not about pushing a shiny, highly curated narrative of Cosby Show-esque Black exceptionalism. Although, after centuries of these destructive images circulating in media and culture being perceived as fact, I do believe we have to overcorrect. Being narrow in any one depiction would also defeat the point. This is about getting to know the depth, beauty, dimension, and range of Black people.

There are numerous content creators and curators doing beautiful important work to combat negative or one-dimensional stereotypes and to bring forth the full humanity of people and communities of color. It’s important to recognize that these sources are largely created for communities of color by people of color, as a means to promote healing, pride, and self-worth, not in an attempt to gain the approval of the white gaze.

Black people have long resorted to looking inward for solutions to their own racial trauma. Any other expectation would be foolish at this point. Regardless of their intended audience, these are just a few examples of the imagery, narratives, and resources that are lacking in general circulation:

TONL

Getty Images Show Us Project

Blvckvrchives

CRWNMAG

Men Thrive

Girl Trek

ARRAY

Code Switch

The Sojourn Project

The Gordon Parks Foundation

As a Black woman, I realize that deeply knowing the fullness of the humanity of Black people is a gift I take for granted. I intimately understand the way, as James Baldwin describes, “When the dark face opens, the light seems to go everywhere.” I have experienced the soul-healing power of our laughter. I have been energized and empowered by the gift of our quick wit, fierce truth, and timely sarcasm; used both as a release valve and a tool. I have known how it feels to be deeply held in an embrace that lingers and sways, back and forth, back and forth. I have been surrounded and uplifted in a chorus of affirming “mmm-hmm,” “yup,” “yup,” “that’s right,” “yes, indeeds” when sharing my pain or testimony within my sister circle. I have known the complexity of Black fathers, uncles, and brothers. Black men who are as “street” as they are strategic. Brilliant thinkers and poetic speakers whose beautiful ideas often multiply in their minds and threaten to consume them for lack of resources or access to the infrastructure through which they can be realized.

I have experienced the quieting depth of my grandfather’s voice. How our family gathered around him when we were broken or shaken and how his stabilizing prayers and lectures pieced us back together and made us feel whole. I have known the gentleness and strength with which he helped raise us. I have known the far-off stare in my grandmother’s eyes, recounting in her mind the horrors of the Jim Crow South, the formative experience of witnessing a lynching and leaving everything she knew to find a better life up North for her children. I have known the love and respect they displayed within their marriage, the dutiful, disciplined cadence with which they created shopping lists, paid bills, and planned meals. I’ve witnessed the gentle intimacy with which they spoke to each other.

I have known the unconditional love and generosity of my mother’s spirit. How it remains like an unlocked door, open to whoever needs shelter, regardless of whether they deserve it. I have reveled in the soothing comfort of my Aunt’s intellect and energy. Her incense, crystals, and collection of Black literary greats like Toni Morrison, James Baldwin, Nikki Giovanni, Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, and Maya Angelou, adorning her Victorian home. I have known the pride and joy of our people at church on Sunday, oiled scalps, pleats pressed and dressed in their best. A congregation and community recharging their weary souls together before starting another long, brutal week.

I have known the silliness and #blackboyjoy of my brothers. Telling jokes and reciting all the words to Coming to America by heart, barely able to get the next line out. Their laughter exchanging punches, doubling them over in hysteria. I’ve also experienced their fierce protection of me as a child, and now, the reversal: my daily concern for their safety as grown Black men. I have been unconfused by their wide-ranging talents and interests, their tenor and bass voices beautifully singing to the collection of Andrew Lloyd Weber followed by Run DMC in the same 1989 afternoon.

These personal, lived experiences have served as important counterweights to the one-dimensional stereotypes that this country seems to perpetuate so consistently. These lived experiences as a Black person, among Black people, allow me to see the full humanity of a man going for a jog or one begging for his life.

My hope for this community of creators is that by recognizing the connection between our own work and the cultural perceptions that impact Black lives, by acknowledging the complicit and overt role our industry has played for centuries in the dehumanization of Black people, we can hold each other accountable to creating and circulating imagery and narratives that aim to reflect and restore the full range of Black humanity within our society and culture.

When our full humanity is widely reflected and personally known, perceptions shift, split-second decisions that were once driven by fear can be overridden by empathy, policies designed to oppress can be redesigned to uplift, talent, and contributions deemed not personally relevant, can assume their rightful place as essential treasures. Black lives can begin to matter.

It is not the responsibility of Black people to lead and do this work. Despite centuries of crushing dehumanization, institutional oppression, racial violence, and trauma, Black people have mustered up the resilience and self-worth to Keep. Showing. Up. with our immeasurable talent and ingenuity, hard work, and humanity in full view for the world to see. It’s about time for everyone else to tune in and share out.

Let’s get to work.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the final deadline, June 7.

Sign up for Brands That Matter notifications here.