Last week, Amazon announced that it would hire 100,000 new workers to handle the surge of orders fueled by the COVID-19 pandemic. Amazon founder and CEO Jeff Bezos framed the company’s role in the crisis as an essential public resource. “We’re providing a vital service to people everywhere, especially to those, like the elderly, who are most vulnerable,” he wrote in a post on the company blog. “People are depending on us.” To sweeten the deal, the company said it would raise its minimum wage from $15 to $17. “We hope people who’ve been laid off will come work with us until they’re able to go back to the jobs they had,” Bezos wrote.

But behind the scenes, workers at multiple Amazon fulfillment centers in the United States are expressing outrage over what they claim are a lack of safety precautions and intense pressure to hit quotas, echoing complaints of Amazon workers in Europe. In interviews with several U.S. workers and labor advocates, Fast Company found inconsistent safety measures, back-breaking productivity expectations, and social distancing guidelines that contravene official public health recommendations. Globally, coronavirus has sickened more than 328,000 people, killed nearly 14,500, shut down schools, restaurants, museums, and bars, and forced millions of citizens to stay indoors. But Amazon warehouse employees are still expected to show up to work in person and even work mandatory overtime to meet elevated demand.

“In terms of the coronavirus, every time you walk through the door, you’re taking a risk,” says one worker at an Amazon fulfillment center in Staten Island, New York, where an employee recently tested positive for COVID-19. “I mean what’s more important, getting people’s things to them or your health?” As of this writing, workers at eight fulfillment centers in the U.S. had tested positive for the novel coronavirus.

Inadequate safety precautions

Late last week at JFK8, Amazon’s massive distribution center in Staten Island, New York, men and women got off the S40 bus and entered the warehouse wearing a variety of protective gear: Some wore N95 masks, the professional-grade respirators that are recommended for treating coronavirus patients. Others donned surgical masks and dust masks. One worker wore a winter face mask.

Coronavirus is highly transmittable in close quarters. That is the logic behind the CDC’s six-foot rule: If the virus becomes suspended in tiny droplets known as aerosols, it can stay in the air for about 30 minutes before settling on surfaces where it could live for hours. Of course, it may be practically impossible to maintain proper social distancing inside Amazon warehouses, according to University of Illinois at Chicago researcher Beth Gutelius, an expert on the logistics industry who has spent years studying warehouse design. Each fulfillment center can employee thousands of staff, all working in various degrees of proximity to one another. Meanwhile, products often get passed between several workers before they end up in the final package that is delivered to the buyer. Scientists have found that the novel coronavirus can live up to 24 hours on a cardboard box and several days on other materials, including plastic. It’s easy to see how coronavirus could spread, if an infected employee worked closely with other workers or even just sneezed on an item.

But workers say the measures aren’t adequate. “They say they’re doing things to protect us, but they really aren’t,” a musician who works at the Staten Island fulfillment center tells Fast Company. “There’s hand sanitizers, the bathrooms are cleaner, and they separated the tables more in the lunchroom. But everybody is still in there together.”

Backbreaking work

The tension is exacerbated by Amazon’s notoriously grueling labor conditions. The company has intense quotas for workers—and they likely haven’t been relaxed, according to Zachary Lerner, senior director of labor organizing for New York Communities for Change, an organization that works closely with Amazon employees in New York. (An Amazon spokesperson told Fast Company that, “Associate performance is measured and evaluated over a long period of time, as we know that a variety of things could impact the ability to meet expectations in any given day or hour.”)

Last November, The Atlantic reported that some workers had to scan a new item every 11 seconds to hit their quota, which translated into hundreds of items an hour and thousands of products a day. This means it can be difficult for workers to take regular bathroom breaks that would allow them to properly wash their hands. “They are telling us to wash our hands and wipe down our stations,” says William Stolz, who works at an Amazon fulfillment center in Minneapolis and is part of The Awood Center, a community group that helps Amazon workers. “But we don’t get extra time to do this.”

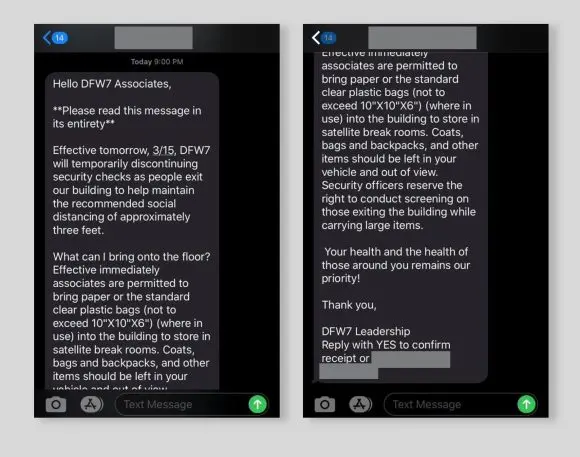

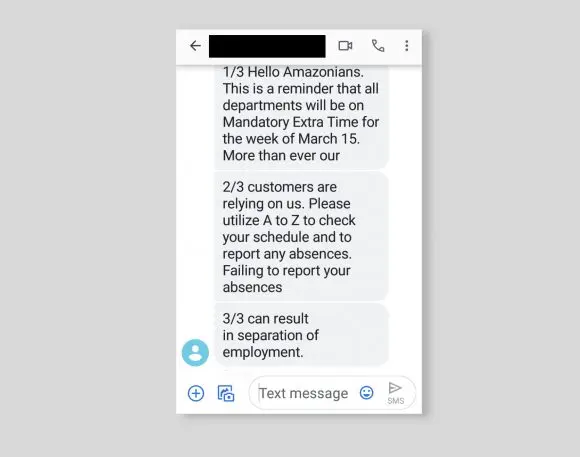

Employees have also been asked to work “Mandatory Extra Time,” according to another text message provided by Athena. The text message, sent to workers in Fort Worth, suggests that if employees decline to work extra hours, and don’t report their absence, it would result in “separation of employment.” (The Amazon spokesperson did not provide more details about how “separation of employment” might occur.)

The right compensation for critical work

Amazon has instituted some policies to deal with the crisis. The company said that it would give workers unlimited unpaid time off until the end of March, as well as two weeks of paid sick leave for employees who receive an official coronavirus diagnosis or are placed under quarantine. But workers’ rights advocates doubt these policies will do enough to prevent an outbreak at a warehouse. “We all know how hard it is to get officially tested right now,” says Dania Rajendra, director of Athena. “And unpaid time off is useless to people who are living paycheck to paycheck. This is creating a situation where workers may show up at a warehouse even when they might feel unwell because they need the money.”

Clearly, Amazon is an indispensable service for the tens of millions of Americans who are sheltering in place at home. According to the New York Times, Amazon’s paper towel and toilet paper sales tripled and cold medicine sales spiked ninefold in the past month compared with a year ago. “It’s undeniable that Amazon is providing a critical service right now,” Gutelius says. “We’re being told that social isolation is the only way to curb the virus. Online ordering allows the rest of us to social distance: For people with fragile health states, ordering from Amazon instead of venturing out to a store could very well save their life.”

If that is the case, Gutelius says companies should be treating warehouse employees like other essential workers during a time of crisis. This would mean, for instance, financially compensating them beyond the $2 hourly raise they’re receiving, she says.

It also means giving them the protective equipment they need to stay safe, like face masks and gloves. At the Staten Island facility, where a worker recently tested positive, an Amazon spokesperson said that workers have access to free personal protective equipment “at multiple free vending machines throughout the building.” But in a blog post, Bezos admitted that his company was having trouble finding adequate protective equipment for workers.

“We’ve placed purchase orders for millions of face masks we want to give to our employees and contractors who cannot work from home, but very few of those orders have been filled,” he wrote. “Masks remain in short supply globally and are at this point being directed by governments to the highest-need facilities like hospitals and clinics. It’s easy to understand why the incredible medical providers serving our communities need to be first in line. When our turn for masks comes, our first priority will be getting them in the hands of our employees and partners working to get essential products to people.”

If face masks are so crucial to employees’ well-being, it stands to reason that Amazon would, at minimum, encourage workers to abide by federal social distancing standards in the interim.

For Stoltz, the Amazon warehouse worker in Minneapolis, the way Amazon is running its operations during this crisis is not just irresponsible toward workers; he believes it could be endangering all Americans. “I want people to understand that this is not being concerned about my co-workers,” he says. “If we’ve got these buildings around the state and around the country that are not abiding by the same social distancing measures that everybody else is abiding by, that’s a risk to all of us.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.