Four years ago, Naomie Charles, who grew up in Boston’s Dorchester neighborhood, started college—a milestone for the mother of two who had experienced homelessness, incarceration, abusive relationships, and other obstacles that had long held her back. Now 32, Charles is set to graduate from Southern New Hampshire University, and though the coronavirus pandemic has changed what that graduation will look like, the people at College Bound Dorchester, the Boston-based nonprofit that supported her throughout her education, will still be there, as they always have.

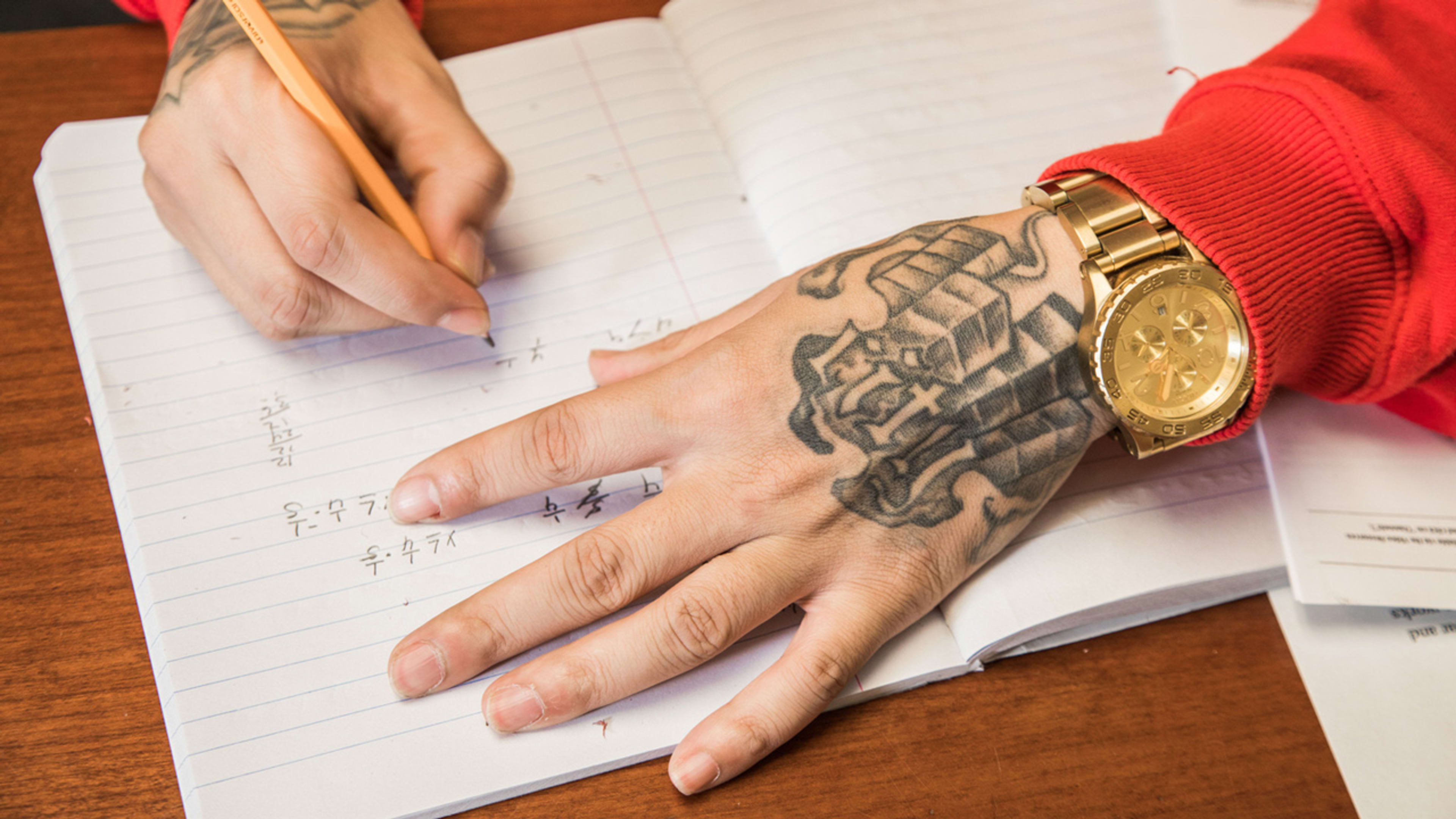

Founded in 2009, College Bound Dorchester supports formerly incarcerated, gang-involved, or otherwise at-risk residents as they get an education, whether high school equivalency or a college degree. In 2016, the nonprofit launched Boston Uncornered, a program that pays a stipend to those former gang-involved students while they pursue their degrees and pairs them with mentors from the same neighborhood and, often, the same situations.

The nonprofit noticed that these students weren’t matriculating at the same rate as other students, partly because they needed financial support to be able to focus on school. “Once we started stipending students, our matriculation rate to college immediately doubled,” from 35% to 70%, says Michelle Caldeira, senior vice president of College Bound Dorchester. More than two-thirds of the participants continue with their college education each year—higher than the national persistence rate.

The stipend—$400 a week while they’re in college for an associate’s degree—was a way to invest in these residents, who are all too often incarcerated or just ignored by society. “By saying, ‘We will put our money where our mouth is—we will invest in you,’ it shifts the whole dynamic of who has the power to transform communities,” says Mark Culliton, founder and CEO of College Bound Dorchester. “It’s really saying to these young people, often for the first time, ‘We believe in your goodness, we believe in your desire to make a positive choice, and we will give you the freedom, autonomy, and support to do that.'”

For Charles, that stipend allowed her to focus on school without turning to her old ways of just trying to get by. “I don’t have to steal, I don’t have to do anything illegal to survive. . . . I can focus on my studies,” she says. She uses her stipend to take care of her children, to cover transportation costs to get to school, and to fill any gaps left by financial aid and other assistance. It gave her a way out of the lifestyle she grew up in, she says, where she was affiliated with gangs, sold drugs, and was generally steeped in danger.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, there were 45 people in Uncornered. Once the crisis began to affect Boston, though, Culliton knew more people desperately needed this financial support. Now, it’s providing direct financial assistance to 125 families (though not all get the full stipend).”That has become more critical than ever, as every other type of support disappeared almost immediately for those families,” he says. The first week of that expansion, in March, the nonprofit put $40,000 directly into the community.

The nonprofit cut salaries for its leadership team 30%, and when it went remote back in March, it made sure that their students could be remote as well, by providing them with hotspots, Wi-Fi connectivity, and other hardware necessary to continue their studies.

Culliton says they’re checking in on each unique situation—whether to help a student who has been sleeping in their car get into safe housing, or by providing that stipend to people who haven’t filed taxes in years because they’ve been incarcerated, meaning they won’t get stimulus checks. “This population, they’ve been scammed and failed by so many systems for so long that it’s only through the fact that we have built trusted relationships through our mentors that they’re even open to the help that we can now provide,” he says.

As for Charles’s graduation, Culliton and Caldeira are working on a way to still celebrate her accomplishment. It’s proof, they say, that investing in these people works—and can make cities better for everyone, by allowing them to leave those lives of violence and crime behind. “One of the things COVID-19 has shown is how interconnected we all are, and how choices that others are making that we never even see are directly impacting those we love the most,” Culliton says. “We . . . understand these powerful individuals in our community will help us all, if we have the courage to invest in them.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.