If the American Century is the past, geopolitical analyst Parag Khanna studies the future. A “new global order has arrived,” he declared in a hotly debated 2008 essay, “Waving Goodbye to Hegemony,” marking the rise of Europe and China as new pillars of a multipolar world. The intervening years have largely proved him correct.

Khanna, of course, has a uniquely global perspective: born in India, raised in the United Arab Emirates, educated in New York and Washington. A policy-wonk wunderkind, he held jobs at the Council on Foreign Relations, World Economic Forum, and the Brookings Institution before publishing his first book at the age of 30. Critics bristled at his precociousness, but Khanna barreled on, picking up fellowships and consulting gigs, hosting an MTV show, and advising U.S. special forces in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The rise of Donald Trump has, in many ways, accelerated the trends Khanna identified earlier in his career—and made him even more skeptical of American governance. Now in his 40s and living in Singapore, the peripatetic think tanker hopped on the phone with Fast Company to talk politics, power, and how to save the presidency from the president.

Fast Company: Let’s start by talking about what’s broken in the American political system. If there’s one thing that both parties agree on, it’s that Washington is too polarized, too partisan to function. What’s your diagnosis?

Parag Khanna: There’s a difference between politics and government. I’m not trying to be a hairsplitting academic, but I want it to be clear that these are not synonymous terms. So when we say things like, “What’s broken in American government?” We turn right away to politics, as if fixing politics would fix government.

But that is a very, very critical point. One of the most important ways to diminish the corrosive impact of partisan politics and money in politics and so forth is to have a government that has its own independent characteristics and bureaucracy and institutions.

FC: You tackle some of these issues in your 2017 book, Technocracy in America, which offers some pretty radical solutions.

PK: Critics sometimes get confused by the term technocracy, which is in no way antithetical to democracy. On the contrary, I advocate radically more democracy. One obvious step is to lower the voting age, which is something that’s being considered or initiated in countries like Switzerland and elsewhere. The most significant step would be mandatory voting, such as exists in Australia. Perhaps the only way to genuinely ensure the statistical legitimacy of an election is to have a high voter turnout. Some even propose that younger peoples’ votes should count more than those of the elderly.

Then the question is, how do you faithfully translate the will of the people into actual policy, or at least into policy options?

So that is the kind of thing that can also be legislated and structured. If you look at California or Switzerland or New Zealand, there are essentially parliamentary committees to take various citizen initiatives and to consider the proposals in committees, to reconcile them and put them forward as potential legislation.

Compare that to the national American system, in which candidates run on a particular platform but then have to make lots of broad compromises and wind up doing very little on any of the aspects of their agenda.

FC: And voters end up feeling exhausted or ignored.

PK: You need to have strong independent institutions that are able to pursue universal agreed-upon policies in a long term way that transcends particular election cycles. In the United States, there’s this problem where we pass Obamacare and then we try to repeal Obamacare. Or with infrastructure, after the financial crisis, we agree that we’re going to spend trillions on infrastructure, then we issue the infrastructure bonds—and bonds are meant to have a 30-year maturity—then we terminate those bonds within two years.

Government needs more people who actually have experience with public administration.”

I mean, that’s the kind of behavior you expect from Argentina, right? So once you decide that something is in the long-term national interest, the key is to invest authority in parastatal entities—bodies run independently of the government but reporting to it. Social Security and Fannie Mae, and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, are supposed to be run like this.

There’s nothing radical or abnormal about creating a national infrastructure governance authority, for example, once you’ve decided you’re going to spend trillions of dollars on roads and bridges. In fact, no citizen or bondholder in their right mind would ever invest on something that important if it were subject to day-to-day politics.

Think about Norway and it’s oil fund: it’s independently managed, but it has a supervisory board consisting of democratically elected lawmakers and the prime minister, and they’re overseeing it and receiving reports annually. It’s as democratic as it gets, but it’s independently managed by experts.

FC: What you call technocracy, then, is more like government by civil servants.

PK: Technocracy is a term that originates in 19th century France, after the country was humiliated in the Franco-Prussian War in the 1870s. The Third Republic wanted to find a way to overcome their decadence. And so they created the famous Grandes écoles academies that are meant to train government elites across a wide range of fields.

So the first thing around technocracy is that it is about public administration, a strong civil service—competent, meritocratic, independent management of the state. The second aspect is utilitarianism. In other words, the moral function of a technocratic regime is the welfare of the people. The greatest good for the greatest number. Otherwise, it becomes a system that’s subject to elite capture. Finally, you need feedback loops between the civil service and the people.

The word technocracy fell into disrepute in the mid 20th century when it came to be associated with the Soviet Union and Communist China—apparatchiks and mandarins driving their economies into the ground. Then it got tied up with the idea of the “best of the brightest” dragging us through the Vietnam War.

But it was used very wrongly all along in the same way that today, if you were to confuse technocracy and authoritarianism, you’d pretty much be missing the point. Some of the most technocratic countries are Germany, Switzerland, Finland, New Zealand, and Canada.

FC: One thing all those countries have in common is a parliament.

PK: The parliamentary democratic system—a multiparty one, to be even more clear— is a much more democratic form of government than ours. The United States, as you well know, is a republic. And multiparty parliamentary systems always rank higher than our republican form of government in surveys of the quality of democracy.

Consider that a member of the cabinet in a parliamentary system is simultaneously a serving representative. There is no Energy Secretary Rick Perry in a parliamentary democratic system. It’s simply not legally possible. And God knows it’s reprehensible anyway, right?

But think about how far removed we are from that democratic practice. Not a single cabinet member in the United States is simultaneously representing anything. Not one of them is an elected individual. But it’s absolutely unheard of on most of the planet. This cannot happen in Canada. This cannot happen in the United Kingdom. It cannot happen in most of Western Europe. Literally, it just cannot happen.

FC: This may be an exception to the rule, but I’m curious how something like the Brexit referendum fits into the paradigm you’re describing. This was a case in which a highly democratic process—a referendum on whether to leave the European Union—resulted in political disaster. Voters didn’t anticipate how impractical the separation would be. And politicians had no choice but to square the circle.

PK: It’s a great example. I think it’s a bit too cynical to suggest that there’s no way the people could have understood. The way the referendum was designed was practically meant to exploit ignorance and could very well have been overcome.

Instead of originating as an election gambit by David Cameron, the details could have been worked out between a parliamentary committee and a committee from the civil service, which is how the British government works out its budgets.

Instead you had a popular referendum independent of any particular election event or cycle with very low turnout and a razor thin margin. So what percentage of the British public actually voted to leave the UK? Democracy should be an attempt to translate the broader will of the people into reality.

When the Swiss hold a referendum, for instance, you have to have a very high threshold of participation of signatories and so forth. The proposal has to be approved in different cantons of the country, similar to how the United States might pass a constitutional amendment. And then the parliament votes. So you have a multistep process that is both democratic and legitimate.

FC: I take all those points. But let’s say that Brexit had been supported by 70% of the population in a high turnout election. In that case, you still have the problem of translating the popular will into workable legislation. What happens when there’s a fundamental disconnect between what people want and what the government can do?

PK: We have those situations all the time.Think about the most obvious example, which is that people always want lower taxes and higher spending. You actually cannot have both, right?

But you can’t expect voters to be juggling all of these trade-offs in their mind when they’re given a binary choice. Why have government at all if we simply believe that every time people want something, that’s what needs to be done? So I think it’s farcical on some level.

That’s why it’s so important to have a civil service that can intermediate—study the issues, calculate costs, and present findings to parliament. MPs can then consult with their constituents, and if people have changed their minds, that gets reflected in elections where those issues are on the agenda.

Let’s be clear: the reason UK governments are falling every week is because they’re having elections without legislation.

FC: In the United States, presidents have responded to political gridlock by expanding their executive powers. Obama did it with immigration reform, for instance, when Congress was incapable of action. But these accomplishments are fleeting. Trump came into office and set about reversing anything that hadn’t been legislated.

PK: One thing Trump has done is to open the window into seeing how many unwritten norms and rules we take for granted. The lesson is that if you want to lock in changes, or restrict power, it needs to be legislated or you have to amend the constitution.

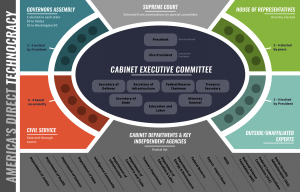

Checks and balances aren’t enough. Perhaps one of the most important changes the United States could make would be to restructure executive authority so that it’s more representative, rather than being purely a separate branch of government. In one model I propose, which is based on the Swiss model, the presidency becomes more like a collective, or a federal executive council, in which the cabinet must include a certain percentage of legislative representatives and governors. So no matter how popular the president is, or by how much she won the popular vote, she would be required to work with cabinet members who are not just friends or family.

FC: You’ve been pretty outspoken about the uselessness of the Senate, and of senators and congresspeople in general taking management roles in government.

PK: Government needs more people who actually have experience with public administration, which is why I think that people who have been mayors of big cities or governors of states are perhaps the only people who are technically qualified to make that next step to be president.

I see nothing wrong with someone who’s been in Congress running for president. They obviously do with or without my permission. However, are they actually qualified to do so? Have they ever governed or administered a large state or bureaucracy and managed a large budget? Being a representative can be fabulous in terms of learning how to capture and express and articulate the will of your constituents. But it doesn’t mean you know how to organize my sock drawer.

This was one of Obama’s problems. What did he ever govern prior to becoming president? And the answer is nothing, absolutely nothing. It’s the same with the people he delegated power to. People say that Obama brought in these technocrats, pals from Chicago law school, Harvard law school, this kind of thing. Well, no. They were knowledgeable advisers. But again, a technocrat is the person who’s actually in the government in a statutory function in bureaucracy running actual programs that constitute billions, if not trillions, of dollars. They work for the government, for the people, not for the president.

FC: In Technocracy in America, you point to Singapore (where you live) as an example of a government that does a better job of integrating data and expert analysis to produce better outcomes.

PK: Singapore is a technocracy in two ways. One, if you want to be in the cabinet, you have to go through cycles of training by occupying different ministerial positions at different bureaucracies. You’ve learned how the ministry of defense works, ministry of finance, ministry of housing, and others. And nobody becomes deputy prime minister until they have been minister of education first—that is how important education is treated. As in Finland, in Singapore, education is religion.

And then by the time you’re actually 50, 55 years old, you literally know how to run a country. You have the experience, 15, 20 years experience running a country. It doesn’t matter if the country is big or small—it’s about experience in public administration.

This is what I call the spiral staircase. You go around and around and get off the rungs and you step on different ministries and portfolios over time. And that makes you qualified to enter the cabinet or become prime minister. In the U.S., our model is the elevator. You get in on the ground floor, you push your button, you go straight to the top.

FC: It’s easy to feel pessimistic about the potential for reform. What’s the single most simple thing we could do to fix some of these problems?

PK: Let me cheat and pick two. One, enforce mandatory voting and lower the voting age to 16. That will do more to “rock the vote” than any campaign that has ever been run on MTV.

If you just have to vote, there’s a psychological effect where you’ll be embarrassed to go into the voting booth and not know anything about who you’re picking. So it has this motivational dynamic, a “nudge.” And obviously you make election day a federal holiday.

This was one of Obama’s problems. What did he ever govern prior to becoming president?”

On the technocracy side, you restructure the presidency as a federal executive council. It seems like something so impossibly radical. But again, this is how parliamentary democracy works. For America, the shortcut is to build a “team of rivals” into the executive branch, with some people coming from the legislative, some from the civil service, and so on.

Again, it sounds radical. But look at Switzerland, which has a federal executive council comprised of seven “presidents,” elected from the legislature, representing different parties. They’re literally not able to get anything done unless they cross party lines. If they don’t, they would all lose their jobs in the next elections.

FC: OK, so what’s the moonshot?

PK: I would abolish the Senate. I honestly would abolish the Senate. And I would replace it with an assembly of governors. Each state would have two governors, and one would remain in the Capitol and one would be that state’s representative in Washington. And they could rotate if they want to, depending on whatever their circumstances or arrangements.

It would be a much more effective chamber. And it’s, of course, actually much more representative of the people than senators are and the way the Senate is constructed. Governors, unlike senators, are actually involved in governance. They also have to work across state borders—on watershed management, railways, infrastructure. Their state will not prosper unless there’s better regional, again, multistate, kind of collaboration.

So, that’s another kind of big idea, blue sky kind of thing. But necessity should be the mother of innovation.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.