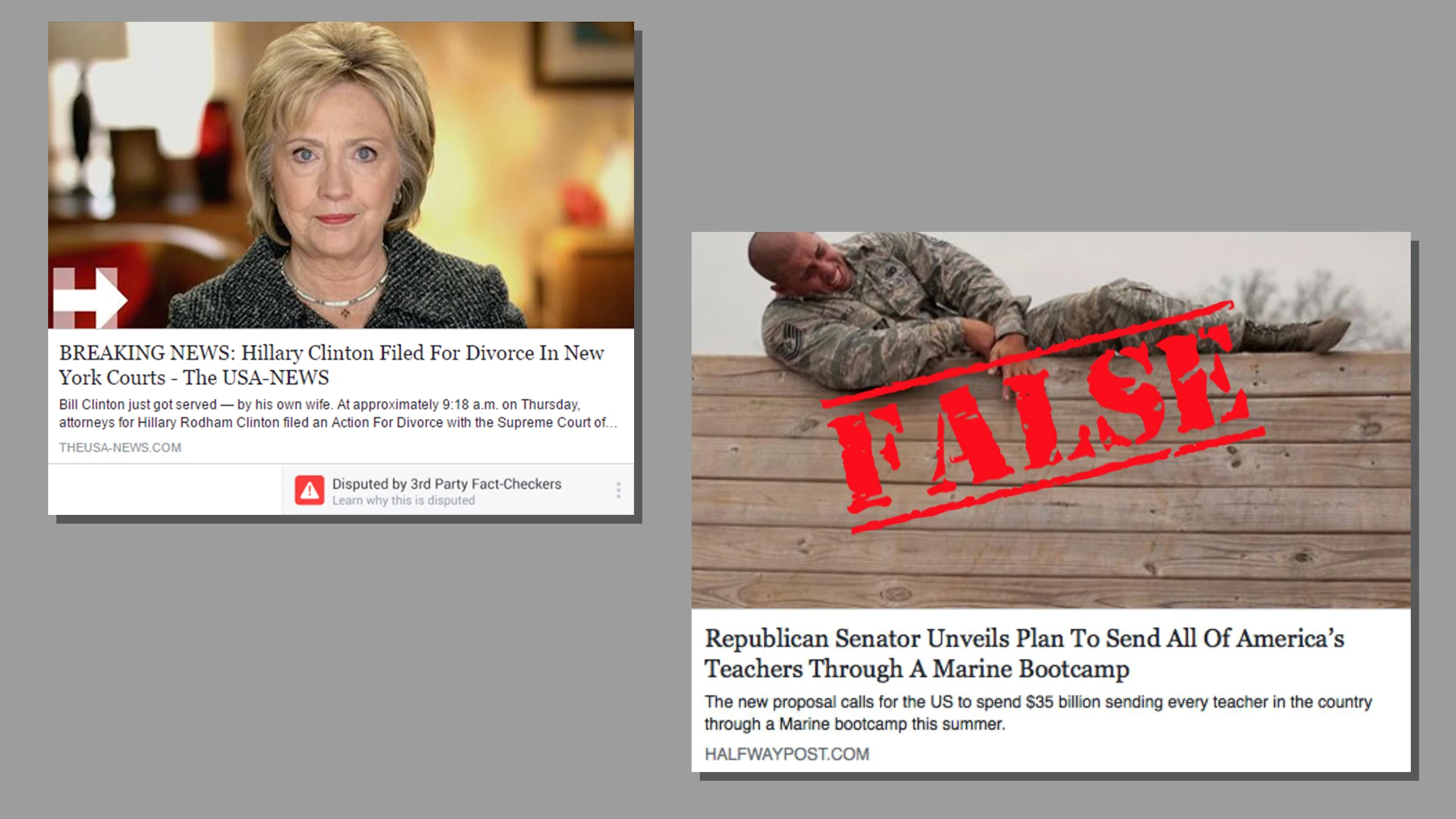

In 2016, after coordinated propaganda on Facebook helped Trump win the election, the social media giant introduced a program for independent fact-checkers to flag fake news as “disputed.” In theory, this was a good thing. While Facebook still wasn’t running every story through a fact-check, deleting false information from its service, or banning unreliable blogs and media outlets from sharing stories on Facebook, it was using the flags to make people think twice before believing a headline or sharing false information. At least Facebook did something.

But according to new research out of MIT published in Management Science, that something was the wrong thing. When only some news is labeled as fact-checked and disputed, people believe stories that haven’t been marked as fact-checked more—even when they are completely false, the researchers found. They dubbed this consequence the “implied truth effect.” If a story is not overtly labeled as false when so many stories are labeled as false, well, then it must be true. “This is one of those things where once you point it out it looks obvious in retrospect,” says David Rand, associate professor of management science and brain and cognitive sciences at MIT Sloan, who led the study. “But in our understanding of years of research people had done on fact-checking, no one had pointed it out before.”

To reach the findings, Rand’s team conducted a pair of studies with more than 6,000 participants. In the first study, people were shown a variety of real and fake news headlines, styled exactly like they are presented on Facebook. Half of the group was shown stories that were completely unmarked with fact-checking of any sort. The other half of the group was shown something more typical of Facebook, a variety of marked and unmarked posts. Then people were asked if they believed the headlines were accurate. (The second study was largely identical to the first, but it used large labels of “false” and “true” that were more overt than they are on Facebook, and participants were also asked if they would be willing to actually share these stories.)

The findings were disquieting. Yes, warning labels did work to flag fictitious content. For instance, when no true or false labels were used, people considered sharing 29.8% of all false stories—yet when false stories were labeled as false, people only shared 16.1% of them. This reduced figure sounds promising, but the twist is that the unmarked false stories were shared 36.2% of the time. That means we are more gullible to share these fake news stories when some are marked and others aren’t.

“When you start putting warning labels on some things, it makes everything else seem more credible,” says Rand. We have a false sense of security because we might assume something was fact-checked when it wasn’t at all. In fact, 21.5% of participants said they believed the untagged headlines had simply been fact-checked.

What is the solution then? Rand, who is actually advising Facebook on this topic (but is unpaid for it), believes there are a few promising ways to avoid the implied truth effect.

First, instead of just flagging content as false, the algorithms in Facebook could demote a publication that’s publishing fictitious content, so that fewer people see its work across the board. The other solution is simply to employ a lot more fact-checkers, so that every news story on Facebook is fact-checked, and they can all be labeled as true or false. Facebook could also simply declare that everything published by The New York Times and The Washington Post is true and fact-checked, due to the rigorous standards these publications operate under. But that would force Facebook to actually admit that truth matters and some publications are more reliable than others.

From other research he has conducted, Rand believes that laypeople could be randomly chosen by Facebook or even paid by Facebook to perform fact-checking. This wouldn’t be a situation where every story is publicly upvoted or downvoted, like Reddit (which would be easily hackable by bots). Think of it more as curated crowdsourcing, which allows Facebook to get feedback while circumventing automation that could sway its results. It’s not that laypeople fact-checkers are always going to be individually right, he says, but that the “wisdom of the crowd” can be averaged for accurate results.

And while better fact-checking certainly sounds promising, Facebook still has to solve another problem: It knowingly leaves up ads, including a recent political ad from Trump, that have been proven untrue. Why? As Mark Zuckerberg put it to Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez while under oath last year, “Well, Congresswoman, I think lying is bad, and I think if you were to run an ad that had a lie in it, that would be bad.” Bad, but not banned.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.