Every day, more than 3,700 people die on the world’s roads. Road traffic crashes result in more than a million deaths and tens of millions of injuries each year, and are predicted to become the fifth leading cause of death globally by 2030, according to the World Health Organization. Some cities have taken steps to reduce these traffic-related deaths through Vision Zero initiatives, but in many places, it hasn’t been enough. So what’s the secret to reducing road injuries? It’s about getting people out of their cars and designing cities around public transit.

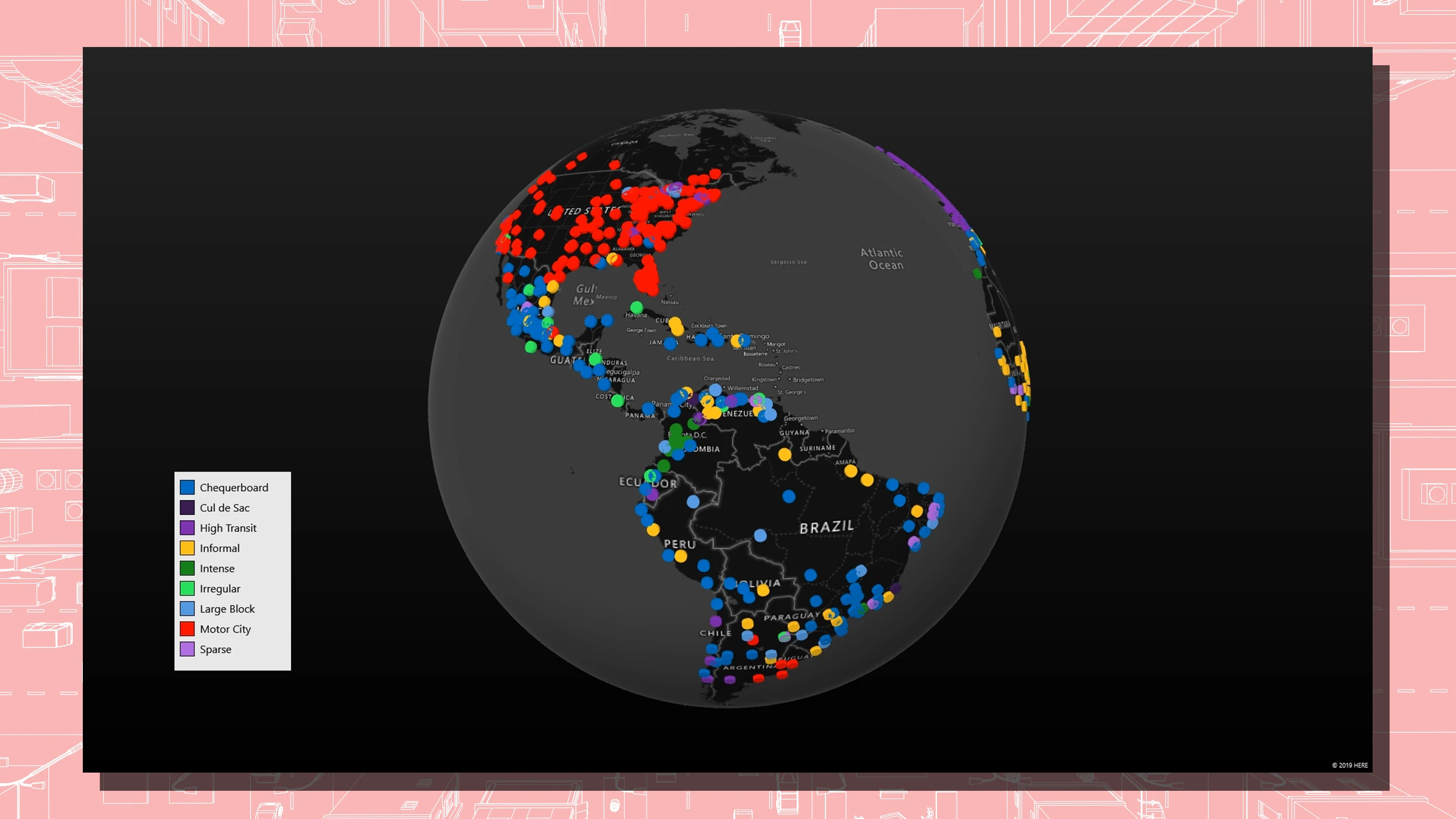

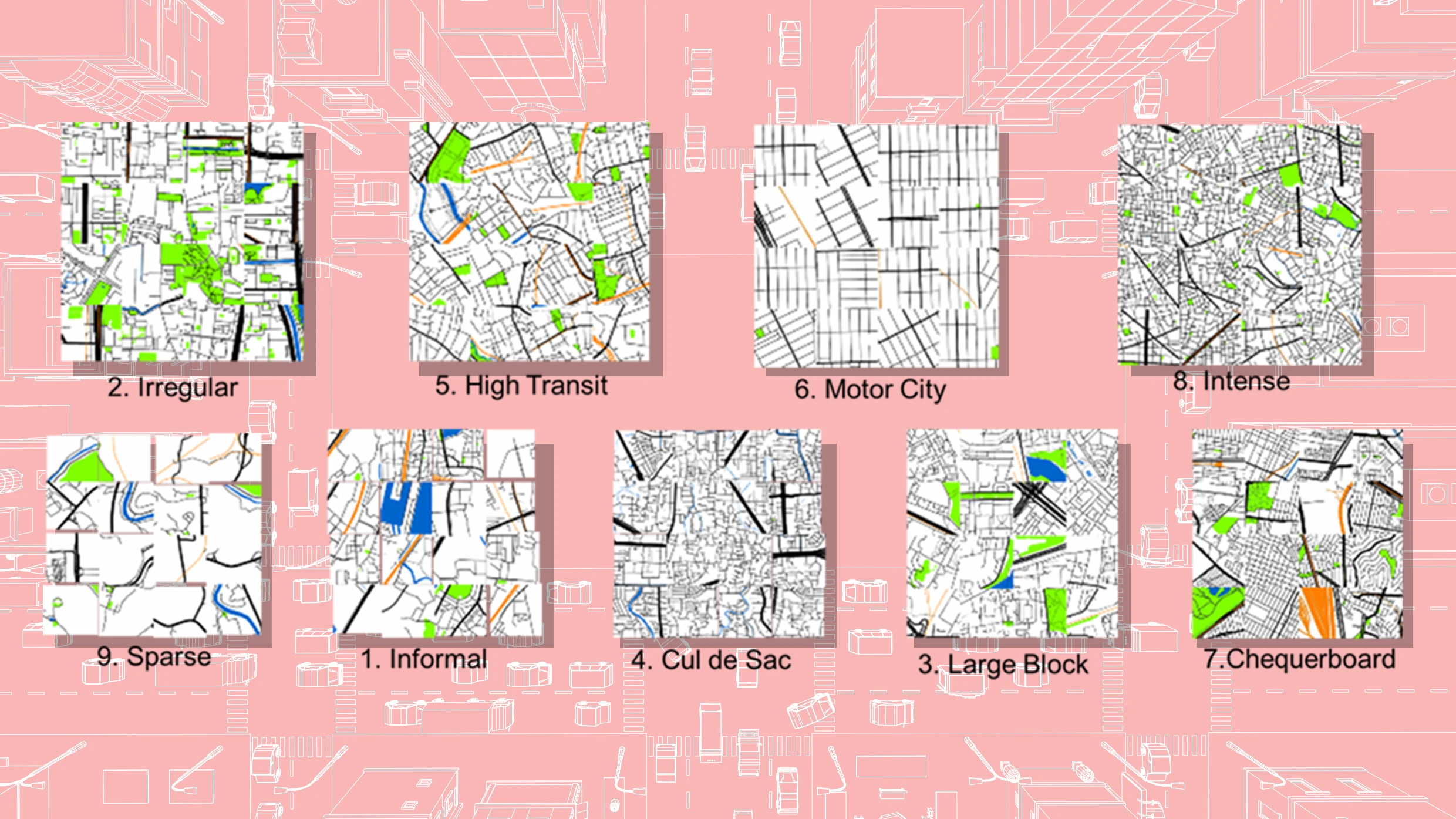

Researchers from Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health; the University of Melbourne’s Transport, Health, and Urban Design Research Hub; and the Barcelona Institute of Global Health looked at the urban roadway design of nearly 1,700 cities across the world, along with local road injury statistics, for a study recently published in Lancet Planetary Health. Lead researcher Jason Thompson from the University of Melbourne wanted to highlight how important urban planning is to reducing such injuries.

It’s quite clear that places that tended to have more available public transit, particularly rail transit, tended to have lower incidents of injuries. ”

Public health researchers have been studying road injuries for years, and Christopher Morrison, an assistant professor of epidemiology at Columbia and one of the study authors, says there has been some progress with reducing the rate of car crashes relative to the amount of people that are driving. “But what this research is looking at is, how does the way we design our cities affect injury incidents and the public health burden?” he says. “What this work very strongly suggests is that the best approach is to get people out of cars in the first place, and to design cities in ways that people are using motor vehicles less.”

By categorizing these cities into design types, the focus was less about identifying specific examples—and thus pointing to one city that is doing it “right”—and more about the specific road designs. “It’s quite clear that places that tended to have more available public transit, particularly rail transit, tended to have lower incidents of injuries,” Morrison says. Those places tended to be Western European cities, such as Paris, London, and Amsterdam. The “cul de sac” type, which represents Southeast Asian cities such as Jakarta, Indonesia, and Nonthaburi, Thailand, and often had mixed transportation use, tended to perform the poorest, meaning they had high road injuries.

The researchers wanted to be broad and simply identify the best “city footprint” for reducing injuries, because there will always be specific examples that run counter to that trend. “In the same way that if you’re studying tobacco use and lung cancer, everybody’s got the excuse of an auntie who smoked forever and never had problems,” Morrison says. “What we were interested in was that average.” The study also didn’t look into other factors that often surround transportation, like congestion, cost, and so on.

It’s to everybody’s benefit to move people out of motor vehicles and into public transit, and the best way we can do that is by improving infrastructure for public transit.”

Still, there are more general takeaways here, too, and that’s because these findings aren’t all that surprising. “It’s concordant with what we know about urban planning from many other studies, which is that where we can divert people away from motor vehicle use and onto public transit, we will improve the public health for the roadway users themselves and also for general populous, reduce risks for injury and death for individuals, reduce congestion, reduce air pollution,” Morrison says. “So it’s to everybody’s benefit to move people out of motor vehicles and into public transit, and the best way we can do that is by improving infrastructure for public transit.”

Improving that infrastructure, though, is a long-term and often cost-heavy strategy that has to fit into a lot of other parts of city life. The researchers aren’t suggesting we immediately restructure our cities, “but it does mean as we’re thinking about new urban development,” Morrison says, “encouraging public transit is a very, very good way of reducing the burden of motor injuries.”

In the meantime, and for all those cities that aren’t planning new urban development but still want to curb traffic deaths, officials from nearly 100 countries will meet at the end of February in Stockholm to discuss what steps they can take to halve their road deaths and injuries by 2030, according to the World Health Organization. That aim is in line with global targets agreed to in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. The meeting in Stockholm will be hosted by the Swedish government in collaboration with WHO, and will end with a declaration that lays out key recommendations and a call for international cooperation to reduce these traffic incidents worldwide.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.