For the last two decades, UNICEF’s temporary schools and health clinics for children in emergency camps have been housed in the same basic tent: A simple, large, multipurpose space that provides basic protection from the elements but isn’t particularly comfortable. Already, on hot days, children sometimes sit outside the tents because it’s too warm to be inside. As climate change makes extreme weather more common, from brutal heat waves to heavy storms, the agency realized that it needed to rethink the tent’s design.

“We had a tent that was designed probably 20 years ago, for the context and environment at that time, that has just proven not to be sufficient anymore,” says Bo Sorensen, project lead at UNICEF’s supply division in Copenhagen. As the team studied what would make a tent work in a changing climate, it also discovered that nothing on the market met its needs—so it decided to help lead the redesign itself, adding it to a list of about 20 products, from advanced medical devices to water jugs, that the agency now has in its innovation portfolio.

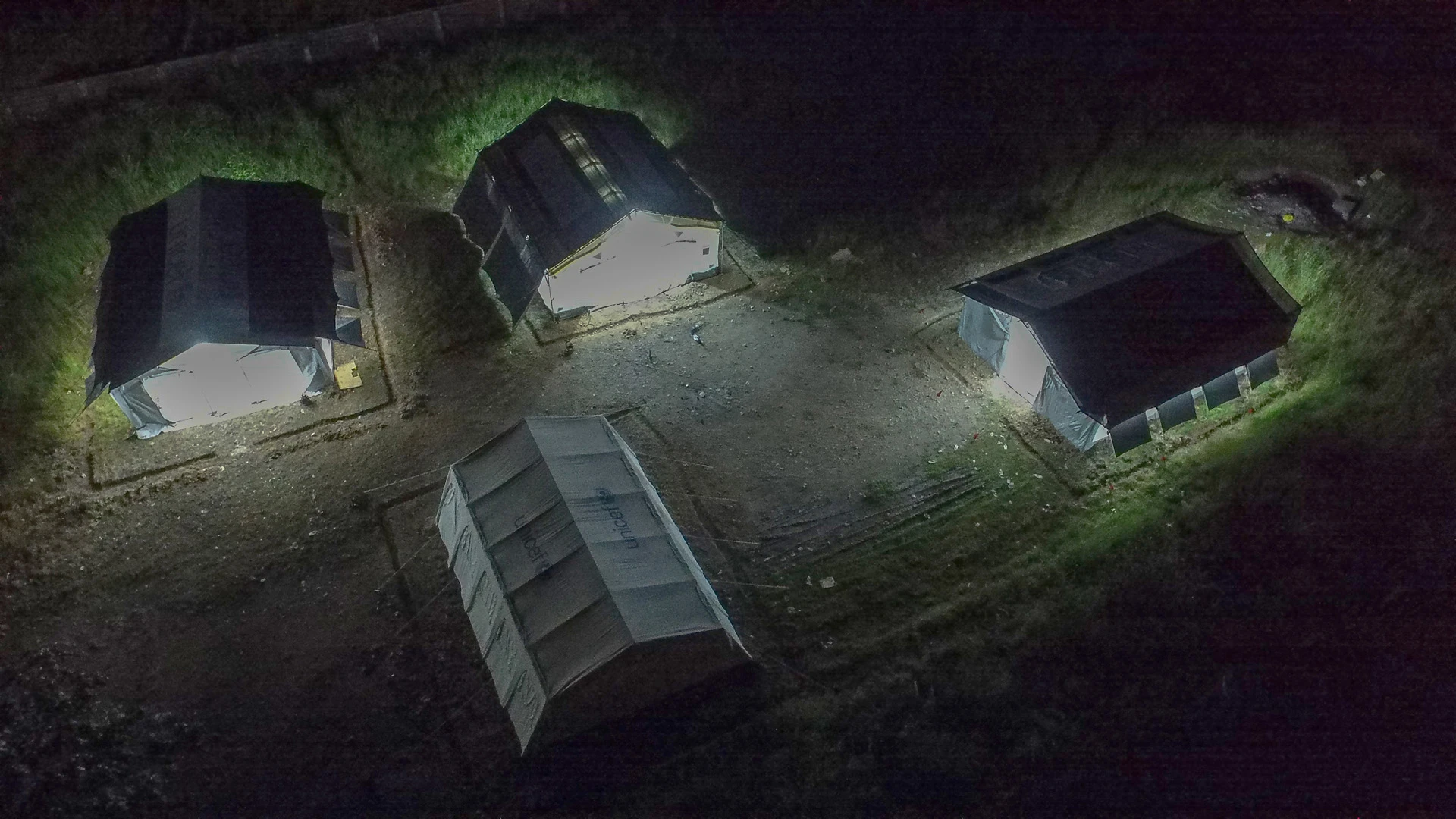

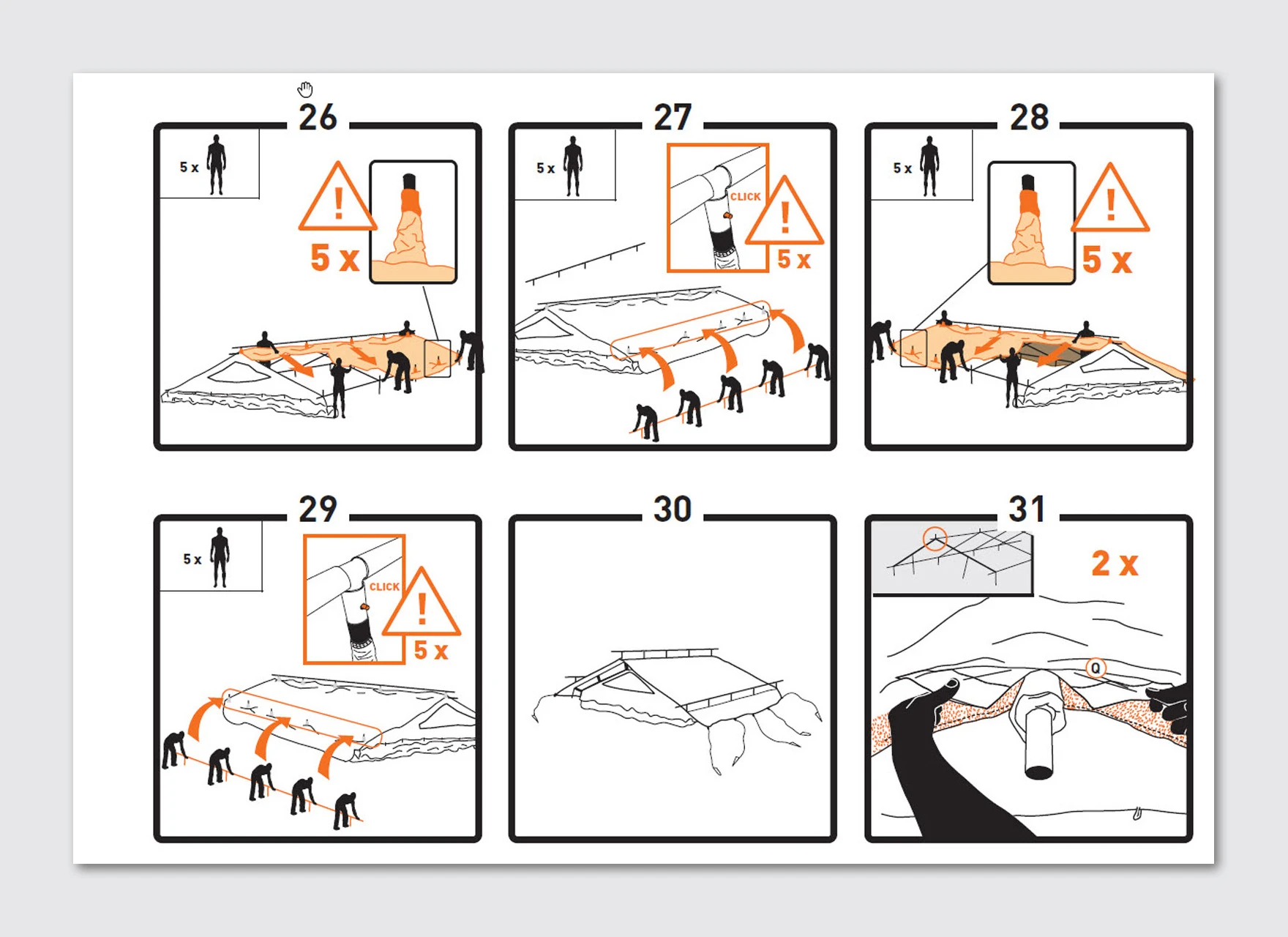

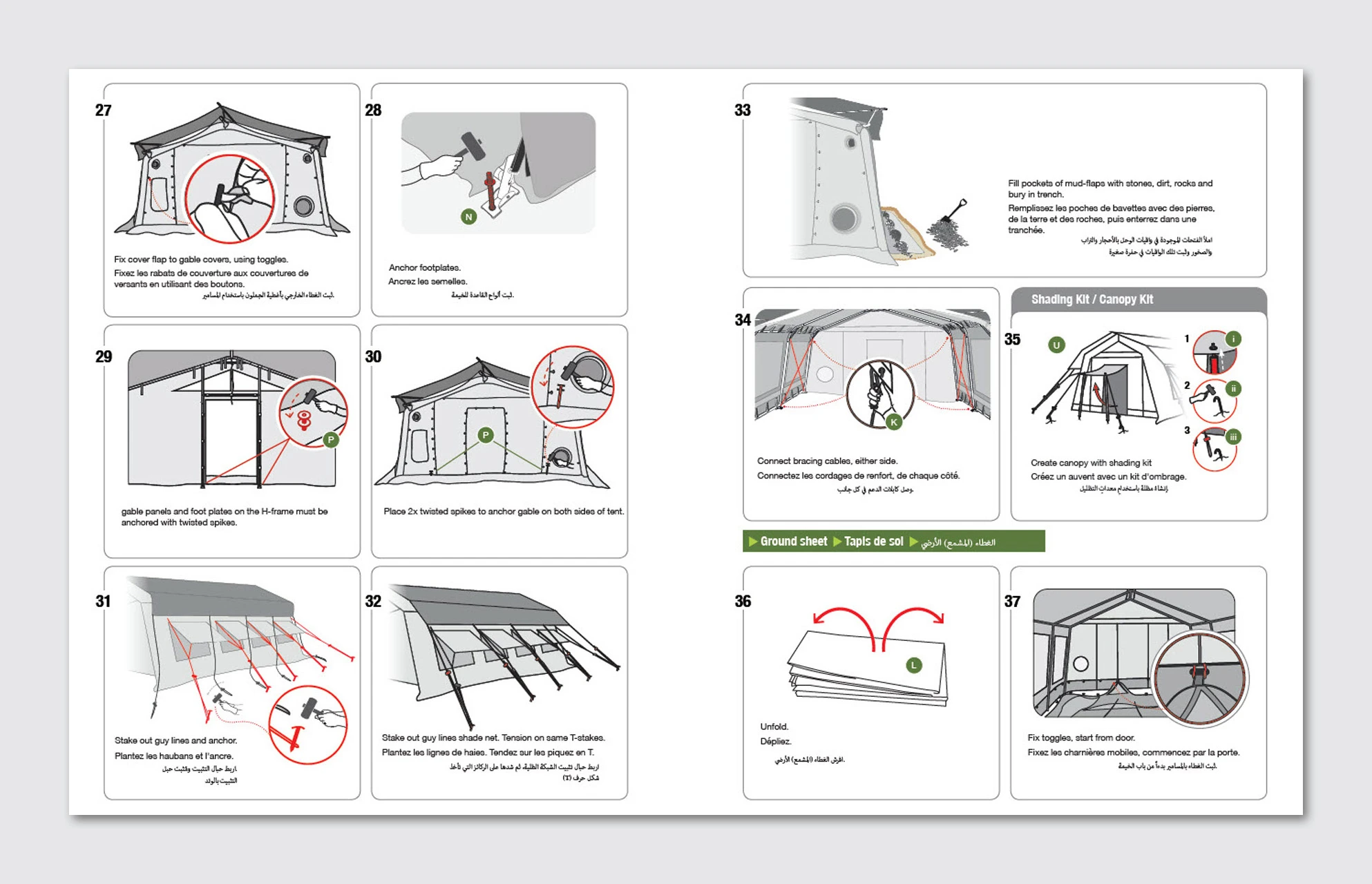

The product was challenging to create in part because it had to be versatile. UNICEF, as the UN agency that works on humanitarian relief for children after natural disasters or conflicts, including at refugee camps, doesn’t provide shelter, but procures thousands of large tents each year that can be used as everything from schools to distribution points and nutrition facilities. The tents are used in emergencies around the world. “They have to be erected by nontechnical people in pretty much all climates known to mankind,” says Sorensen. “We erect them in cold climates where we have snowstorms and subzero degrees, and very hot climates in deserts. The tent has to fit everywhere.”

The team started by interviewing everyone who interacted with the tent—including warehouse workers and customs officials, not just refugees. “We are not only focusing on the end user, which has kind of been the typical way of thinking in design in the last 20 years,” he says. “We tried to have a more holistic approach.” The interviews led to a staggering list of more than 1,000 requirements for the new tent, including how the crates holding the tent should be labeled, how easy it should be to put up, and the maximum wind speeds it should be able to withstand.

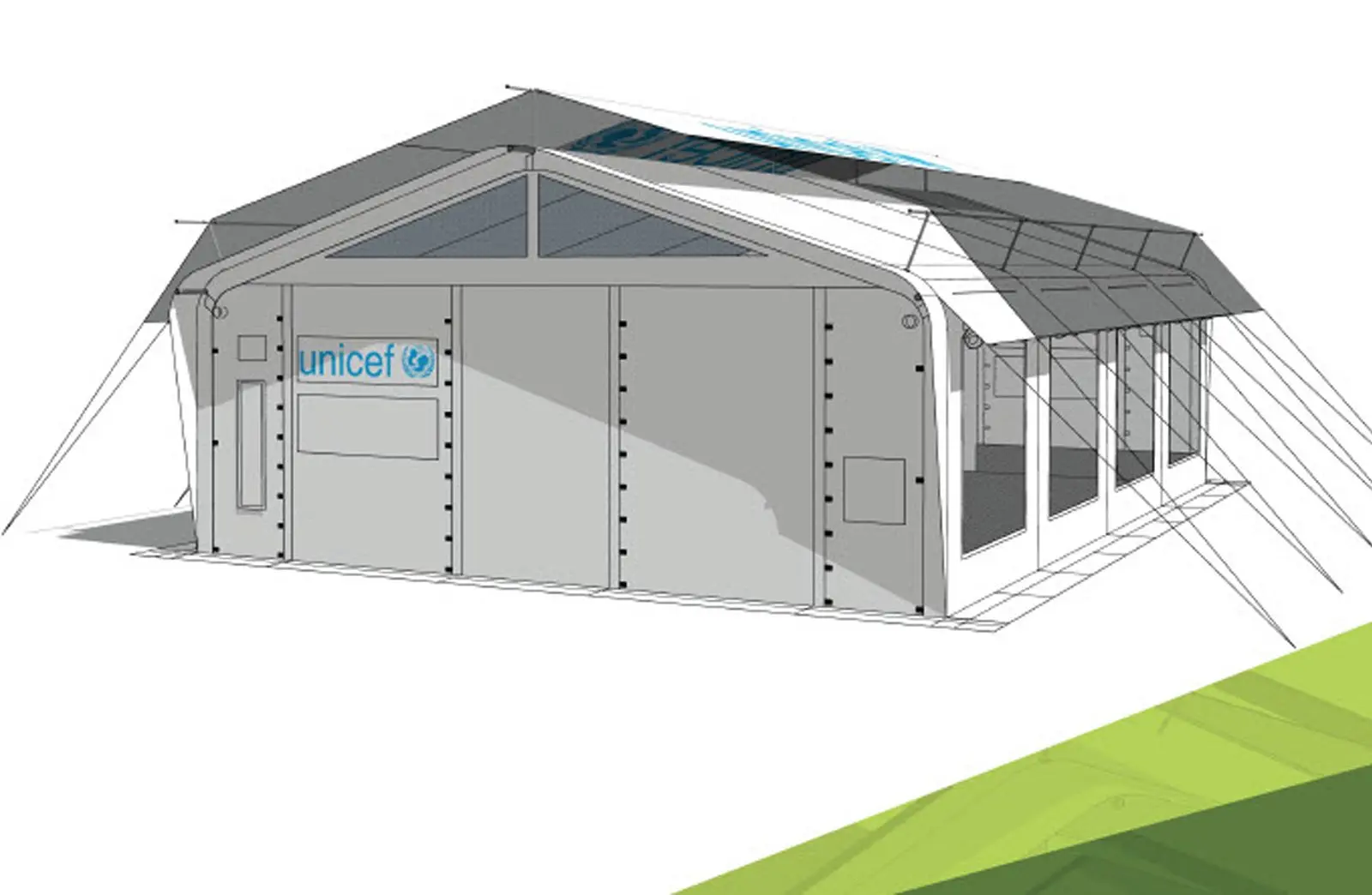

The final design used several tweaks to become stronger, including improvements in how the tent is anchored in the ground, the quality of the tent’s frame, and the position of guy ropes. (When the tents were eventually tested in a wind tunnel, they withstood hurricane-level winds.) On hot days, the tent stays cooler because of large mosquito-net-covered windows on opposing sides that improve airflow. Outside, a second layer above the roof, called a shade net, helps deflect the sun and creates a wind tunnel that blows air down into the tent. In a heavy storm, the shade net is designed to also prevent rain or snow from building up and collapsing the tent. For colder climates, it has a winter liner that can be added to keep it insulated.

But creating the right set of instructions, easily understandable by refugees or others who would have to erect the tents, was also a critical part of the design. “You can have the best tent in the world, but if it is installed incorrectly, it will blow away during the first storm,” says Sorensen. The instructions are available in English, Arabic, and Spanish, and for those who can’t read, video tutorials are available via smartphone.

Since the tents also had to work in several situations, they come with optional add-ons: A temporary hospital, for example, might choose to add the kit’s solar panels and a hard floor that’s easier to keep clean. The prototypes were tested in three climates—hot and dry Uganda near the border with Sudan, the humid Philippines, and cold Afghanistan. This year, as old tents wear out, the new ones will take their places. The first prototypes were donated locally and are already in use. “Now we are getting the feedback from the real users of the tents,” says Sorensen. “And so far, it has all been positive.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.