Pete Buttigieg is discussing a Canadian supermarket chain, and he’s getting excited. “My real specialty at McKinsey was grocery pricing,” he says onstage at the Commonwealth Club of California, waving his arms as he describes analyzing “this ridiculous database of zillions of lines of data” for a client during his three-year tenure at the prestigious global consultancy that insiders refer to, with a combination of reverence and affection, as The Firm. “Believe it or not,” he says earnestly, “that was really intellectually formative.”

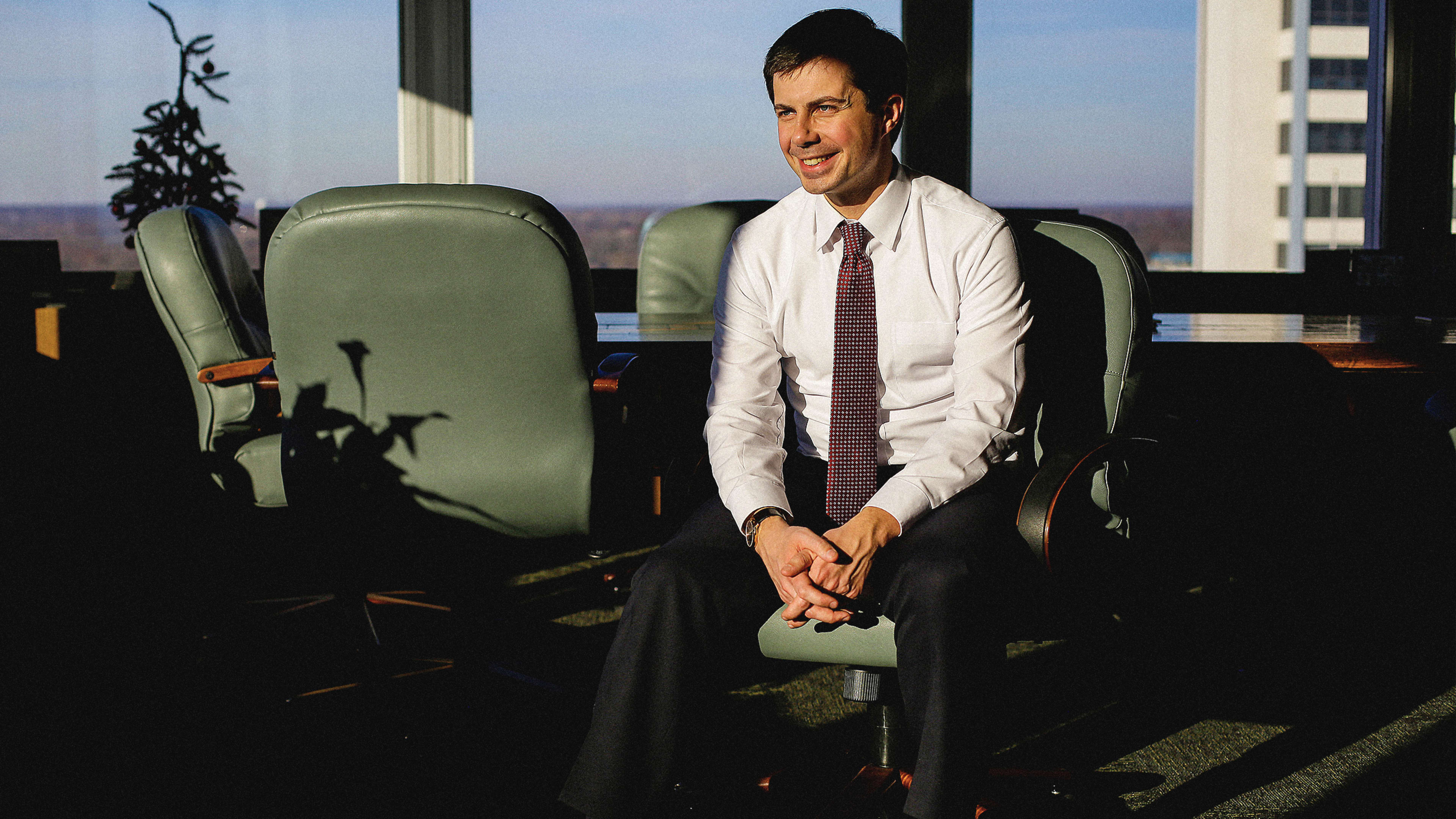

The 37-year-old mayor of South Bend, Indiana, is wearing his usual politician’s uniform: white dress shirt and dark tie, his sleeves rolled up like a car salesman or a missionary. It’s early April, and Buttigieg is on the cusp of a boomlet that will eventually lead him to the top of the Democratic primary polls in Iowa. But while the press is gushing over his Renaissance-man credentials—Harvard graduate, Rhodes scholar, musician and Afghanistan War veteran, fluent in seven languages—a backlash is building on the left.

“McKinsey has been in some big scandals lately,” the interviewer points out. It’s a preview of what will come to be the defining challenge of Buttigieg’s unlikely candidacy: how to convince Democratic voters, many of whom are disdainful of elite corporate interests, that the precocious 2020 aspirant is more than a C-suite sympathizer programmed to triangulate political positions and generate soundbites. Buttigieg’s eyes, which until now have been sparkling, narrow somewhat, and his face becomes impassive, as if calculating an answer optimized to appease all stakeholders.

“It really depends a lot on the client and a lot on the engagement,” Buttigieg says carefully. “You don’t think badly of a law firm because some of the clients they serve are doing bad things . . . but, you know, everybody’s not entitled to management consulting.”

* * *

The debate surrounding Buttigieg’s stint at McKinsey has grown more contentious in the eight months since his remarks at the Commonwealth Club. Now on the verge of a potential first-place finish in the Iowa caucuses, the controversy—over McKinsey’s work for China, Saudi Arabia, and the maker of OxyContin, to name just a few of its suspect clients—has ensnared the mayor in a full-blown public relations crisis. Throughout the fall, critics called on Buttigieg to disclose the nature of his work for the secretive firm. Bound by an NDA, he stayed mum. When Buttigieg pivoted to the center on Medicare for All and student loan debt, left-leaning publications such as New York magazine dismissed him as a political chameleon and a corporate shill.

The steady drip of criticism became a deluge in early December, when the New York Times and ProPublica published a story alleging that McKinsey worked with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement in 2017 to facilitate the Trump administration’s crackdown on illegal immigration. Buttigieg said he found the Firm’s actions “disgusting” and “extremely disappointing,” emphasizing that they took place years after his tenure, but no matter. The narrative of “Pete for Corporate America” had gone mainstream. (McKinsey, which has called the Times‘s reporting “misleading” and “inaccurate,” declined to comment for this article.)

Finally, after wrangling with McKinsey to be released from his NDA, over the course of a painfully slow-motion news cycle, Buttigieg published the names of all the clients he served—spawning a second wave of speculation about the nature of his service to each one. In a surreal twist, the Buttigieg campaign was forced to put out a follow-up statement denying that his work for the Canadian supermarket chain Loblaws had anything to do with a bread price-fixing scheme.

But interviews with Buttigieg’s former colleagues suggest that the presidential hopeful’s deployment in the trenches of corporate America was both more complicated and more banal than it would appear. McKinsey circa 2007 was in many ways a different institution than the McKinsey that exists today. For starters, it was much smaller. Over the last decade, the Firm has more than doubled in size, now boasting 27,000 employees. McKinsey has also made several acquisitions, adding capabilities in areas such as design thinking and data analytics. What is today a sprawling global operation felt more like a tradition-bound partnership in the year that Buttigieg joined.

The Firm’s reputation at the time was “relatively unblemished,” in the words of one former associate. If rival consultancy Bain attracted frat boys, McKinsey recruited library-loving intellectuals. Chelsea Clinton, following her Rhodes scholarship, worked at the Firm for three years in the mid-2000s, leaving just a year before Buttigieg started. Elizabeth Warren’s daughter launched her career there as well. (I worked as an analyst in McKinsey’s New York office from 2006 to 2008; I have never met Buttigieg.)

“For me, the Firm took a fairly unskilled 22-year-old and made me a productive human being,” says one former analyst who worked alongside Buttigieg. “I think there is no better environment to be exposed to a lot of different things and through those projects and clients and roles build out a skill set that can allow you to effect change on a really global scale.”

The education one received at McKinsey was typical of other white-shoe consultancies at that time. Associates without prior business or finance experience, like Buttigieg, were required to attend a Firm-designed “mini-MBA” program before their first project. But for the most part, junior consultants learned on the job. They were trained to use Firm frameworks and techniques of yore, like whiteboarding “MECE” decision trees (shorthand for mutually exclusive, collectively exhaustive). They were told to be “hypothesis-driven.” They were also expected to become comfortable with analyzing data, producing slides, and presenting to clients.

If junior consultants had any complaint in the late 2000s, it was over the gap between the Firm’s recruiting approach, which spotlighted projects with a social-good component, and the unsentimental reality of working for Fortune 500 clients. Eventually, McKinsey modified its on-campus messaging to more clearly convey that new recruits would spend the majority of their time serving large for-profit corporations with budgets that could sustain McKinsey teams, not nonprofits intent on saving the world. During the Great Recession, when banking and consulting jobs became scarce, no one did much complaining at all.

Life at McKinsey followed a typical consulting rhythm, with Monday through Thursday spent on-site with the client, and Friday spent back home. On weekends, Buttigieg liked going to plays at Chicago’s famed stages, including the Goodman and Steppenwolf theaters.

Former consultant Gautam Kumar recalls having a beer with Buttigieg during a Friday happy hour at the Chicago office. “I remember thinking at the time that he talks like a partner—super well-spoken, super articulate.”

In 2008, roughly a year into his residency at the Firm, Buttigieg landed a role on an energy efficiency project cosponsored by a coalition of government agencies, nonprofits, and utilities. For Buttigieg, it would have been a coveted assignment: only the best and brightest of McKinsey’s best and brightest were able to win roles on “firm knowledge” projects, a type of engagement designed to produce public-facing reports and bolster McKinsey’s credibility as an expert on a particular topic.

“Pete was very deliberate about what he wanted to work on,” says Melissa Hayes Potdar, a fellow South Bend native who was an associate consultant in Buttigieg’s Chicago cohort. “He worked to really influence his McKinsey path.”

The energy efficiency team, based in Connecticut, worked long days. The project was “intense,” “high-profile,” and “kind of insane,” say consultants who contributed to the work alongside Buttigieg, with the large number of clients—including the Environmental Protection Agency, the Department of Energy, and the Natural Resources Defense Council—adding to the complexity. “[Buttigieg] didn’t complain a lot,” one former colleague says. “He was calm under pressure.”

Melissa Hayes PotdarI think his time at McKinsey gave him an opportunity to build his leadership and get exposure to smart leaders. You could tell he wasn’t gunning to be a partner.”

Buttigieg’s “workstream,” or area of focus, was identifying behavioral barriers to improving energy efficiency. Many people don’t turn off their lights when they leave home, for example. Or, as the team’s final report states, “a facility manager might replace a broken pump with a model having the lowest upfront cost rather than a more energy efficient model with lower total ownership cost, given a lack of awareness of the consumption differences.” Buttigieg analyzed such behavioral barriers, in residential as well as industrial contexts, and also spent time thinking about the “why” of people’s behavior.

“He did a lot of research, but I could tell he was very high-empathy in terms of his understanding of human psychology—why people might not do things, and what are the solutions that would address psychological or financial barriers that people would have,” a former teammate says.

Another teammate recalls that “Pete was very much recognized as [the person to seek out] if you needed a stable, clear head to talk something through.”

The energy efficiency project was one of eight that Buttigieg completed during his roughly three years based out of McKinsey’s Chicago office. He impressed the Firm’s leadership with each assignment, positioning himself to transition from slide jockey to team manager or salesman. But Buttigieg had grander ambitions, and they did not include the McKinsey partner track. After a leave of absence in 2008 to support the gubernatorial campaign of Indiana Democrat Jill Long Thompson, Buttigieg quit McKinsey for good in 2010 to run for state treasurer of Indiana, a race he lost.

Potdar, a close friend, says she talked to Buttigieg frequently as he was preparing to exit McKinsey. “He just had a vision,” she says. “I think his time at McKinsey gave him an opportunity to build his leadership and get exposure to smart leaders. You could tell he wasn’t gunning to be a partner.”

* * *

Over the last several weeks, Buttigieg has tried to demystify the arcane nature of his work, providing new details about his assignments in an interview with the Atlantic. But the narrative he will have to resolve, in order to have a shot at winning the Democratic nomination for president, has less to do with what he did at McKinsey and more to do with why he joined and what he learned there. At a moment when unreconstructed capitalism is under attack, that will not be an easy task.

For Buttigieg, like many of his peers, McKinsey was more than a corporate training ground. Perhaps more important, it was a means to gain access to a powerful professional network. Roughly one in five McKinsey alumni go on to become entrepreneurs, and many more achieve positions of influence in their respective industries. McKinsey alumni have cofounded startup unicorns including Careem, Compass, DoorDash, Grab, Oscar, and ZocDoc. They also lead companies such as Google and Mattel.

In recent comments about his McKinsey experience, Buttigieg has not mentioned the relationships he formed. Instead, he has focused on the business acumen he acquired and the chance to make money. “If you’re going to manage the largest economy in the world, it’s probably a good idea that you’ve had a little bit of professional experience looking at a balance sheet or knowing what an income statement is,” he told the Atlantic. He also said, “And of course, I needed income. I’m not going to pretend that I wasn’t earning a paycheck too, and knew that.”

Of course, in a Democratic primary defined by a rising tide of populism, a businesslike demeanor cuts both ways. Buttigieg’s professional networks and client-facing communication skills have made him sound far older and more experienced than his 37 years. Standing next to Joe Biden (age 77), Bernie Sanders (age 78), and Elizabeth Warren (age 70), it’s clear that those assets have helped to alleviate concerns about his preparedness for the presidency, especially with Democratic voters over age 65, 12% of whom say Buttigieg is their first choice. The phenomenon is even more notable in Iowa, where 23% of seniors support Buttigieg, making him the second-most popular candidate. But with younger, more liberal voters, the McKinsey Way has revealed its limitations. Among voters 18-29 nationally, only 7% describe Buttigieg as their first choice for the nomination.

Still, Buttigieg’s data-driven approach may yet carry him through to the nomination, particularly if he’s able to pull off a momentum-building result in Iowa. To make inroads in early primary states, he has tacked toward the center on two of the issues central to the Democratic contest: student loans and healthcare. His $500 billion plan to make college more affordable, for example, would mostly support families making less than $100,000 a year, rather than erasing existing student debt in the more universal fashion that Sanders and Warren have proposed. On healthcare, he has reversed his earlier support for Medicare for All; instead, he is advocating “Medicare for all who want it,” a model that he says would have a better shot at passing Congress.

For Democrats who lean far left, Buttigieg’s education at McKinsey makes these policy positions suspect. His first client, after all, was Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan—which cut hundreds of jobs two years after Buttigieg cycled through. “It certainly explains a lot,” Congresswoman Pramila Jayapal said recently. Jayapal, like many other Democrats in Congress, would prefer a single-payer public system like the National Health Service (NHS) in the United Kingdom.

But, as ever, the truth is more complicated. The consultancy tasked with helping design and reform the National Health Service over the years? That would be McKinsey too.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.