For anyone desperate to participate in a big health study, your time has arrived: Apple’s Research App is now live. The app was first announced in September around three new studies. One focuses on menstruation and women’s health, and is open to iPhone users. The second two, which study hearing health and the relationship between mobility and heart health, both require an Apple Watch to participate.

The new app is a part of Apple’s big push into healthcare. The company has cozied up to the American Heart Association, The World Health Organization, and the National Institute of Health, not to mention major research institutions like Harvard’s School of Public Health, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and the University of Michigan. Researchers have made no secret that they see big opportunities to learn about human health through all the data being collected by Apple’s devices. But rather than doing one-off studies, which Apple has done in the past, the Research App allows the company to operate multiple studies at once for a variety of organizations. In this way, the new app is a key way for the company to make nice with the healthcare industry and also to better understand how its devices make sense as health tools.

Upon opening the app, users will be faced with a memo explaining that all the studies in this app are reviewed and approved of by an independent ethics committee. Then it’s time to talk privacy. The following screen tells users that their data will not be sold, that only they can chose what studies to join, and that they can make choices about what data they want to share. It also says that a person can stop sharing data at any time. However, once you have contributed data to a study, you cannot retract it. Still, there is a 24-hour window within which you can stop your data from being sent to the study if you happen to change your mind about participating. Additionally, the app will ask participants to re-enroll every two years, just to make sure they still want to be part of the study.

Meanwhile, the heart and mobility study requires an Apple Watch. The device will track activity levels and periodically ask participants questions about their health, like “Do you have difficulty walking up stairs?” Or, “Does it take you a long time to stand up after you’ve been sitting down?” The study is expected to last five years and aims to unearth early warning signs of chronic disease like atrial fibrillation, heart disease, and loss of mobility.

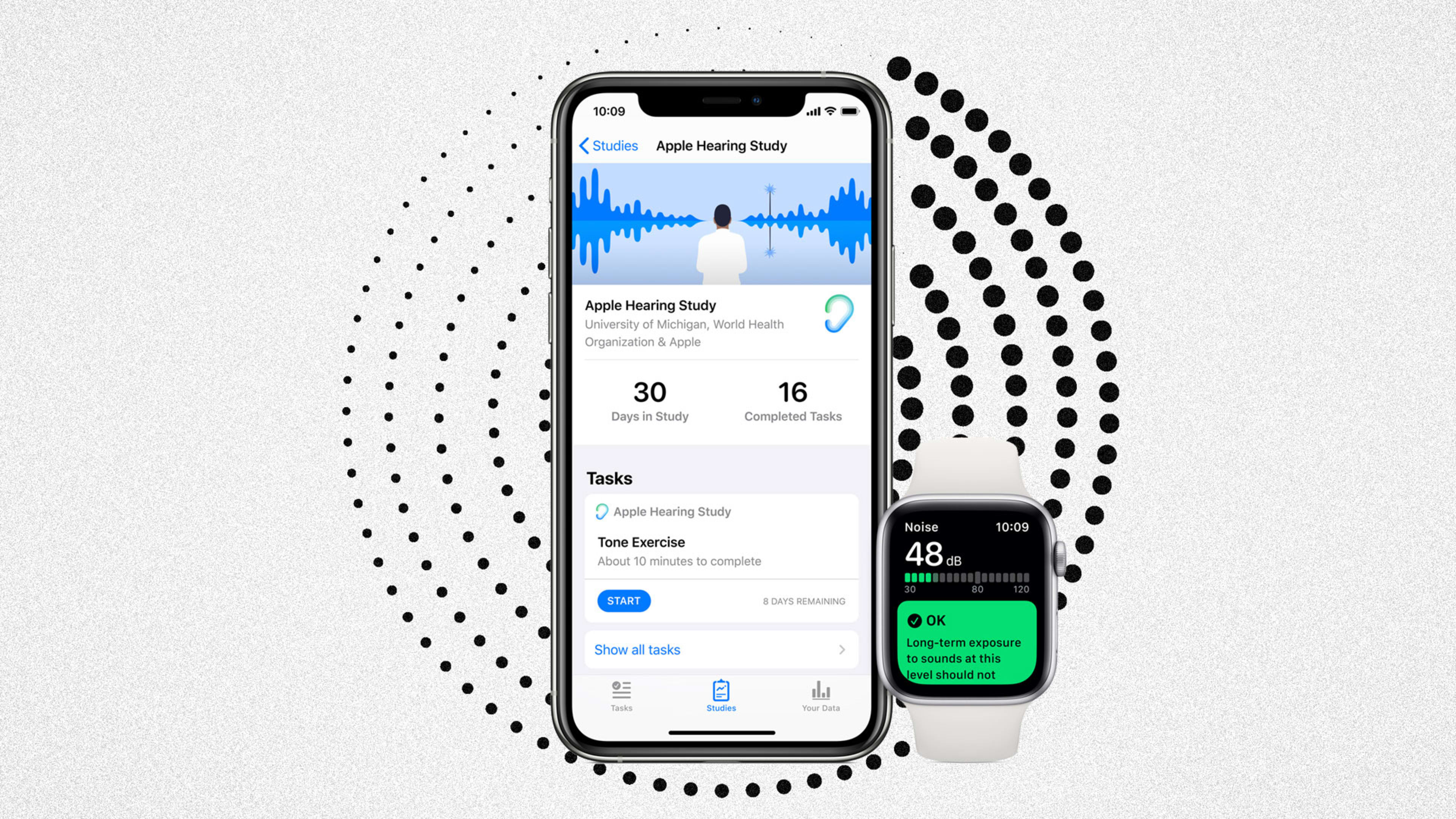

The hearing study will only be two years. This one can use the Apple Watch, but only requires an iPhone which will log environmental sound. Apple says that the watch will not be listening or recording sound at all. Instead, it will be logging decibel levels. If a high decibel level is detected, the app will serve participants a questionnaire about what kinds of sounds they were exposed to and for how long. With all three studies, there is the option to incorporate a participant’s electronic health record, if it is located within one of the 400 systems that Apple integrates with.

In addition to helping researchers better understand mechanisms of disease and health, these studies give Apple insight into how it can make more desirable health products for more than a billion customers.

In March, Apple publicized the results of an eight-month study that measured the Apple Watch’s ability to detect irregular heartbeat and monitor for atrial fibrillation (it has since been published in the peer-reviewed New England Journal of Medicine). The study affirmed the watch can screen for atrial fibrillation among a previously undiagnosed population, but that it should not replace medical grade diagnostic tools. Researchers from that study are now considering the Apple Watch’s capacity to detect other kinds of irregular heartbeats. They are also thinking about what would have to change for the watch to be more equipped to help people manage atrial fibrillation once they are diagnosed.

“It’s our job in the clinical community and all of us have to think about where these fit,” says Mintu Turakhia, a cardiac electrophysiologist at Stanford University and an investigator on the smartwatch study.

In this next slate of studies, both the iPhone and the Apple Watch will be involved in far less targeted explorations. In the near-term, these studies have the ability to prove Apple’s ability as a research tool. In the long-term, they may help Apple cement itself into the health industry.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.