Much like certain perspectives have historically been shut out from the mainstream, certain art forms have, too. Quilts are one such medium, often pushed outside of the traditional fine art world and relegated to the status of mere “arts and crafts.” But a recent gift to the UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) promises to elevate the rich history of these textiles—thoughtful, thread-heavy works of storytelling through design—to the level it deserves.

The Northern California arts institution in October received an unprecedented donation of African American quilts, to the tune of 3,000 different pieces; the entire collection (reportedly the largest private collection of works by African American quiltmakers) belonged to art scholar, psychotherapist, and passionate heritage quilt collector Eli Leon. The team at BAMPFA wasn’t aware they’d be receiving his treasure trove of textiles until after his death in 2018, and is currently in the throes of handling the instantaneous growth of their 20,000-piece collection by a whopping 15%.

“We have a gift that suddenly establishes a critical mass of our collection,” says Lawrence Rinder, director and chief curator of BAMPFA. “I had acquired one Rosie Lee Tompkins quilt for the museum from Eli about six or eight years ago, and we owned two Amish quilts . . . beyond that, we have relatively few textiles of any kind. We do have a very significant and strong collection of African American art, but in the more traditionally fine art [realm].”

BAMPFA’s art database has been steadily growing since 1870, but Leon’s gift represents one of the most significant in the museum’s history. Much like the 1,000 Japanese prints donated by a Berkeley professor in 1919, and scores of abstract impressionist paintings bequeathed to the institution decades later, “this gift is going to have a similar impact,” Rinder says.

Rinder was first introduced to Leon and his dedication to the quilted form when he saw one of Rosie Lee Tompkins’s quilts in a show at the Richmond Art Center sometime in the early 1990s. Leon was a steadfast supporter and patron of Tompkins, who hailed from the south but built her quiltmaking career in California’s Bay Area. Rinder and Leon would continue to build on their relationship when Rinder mounted Tompkins’s first solo museum show at the Berkeley Art Museum in 1997. “He knew that I shared his view that these quilts transcended this idea of craft and did rise to the level of art in a very profound way,” Rinder says.

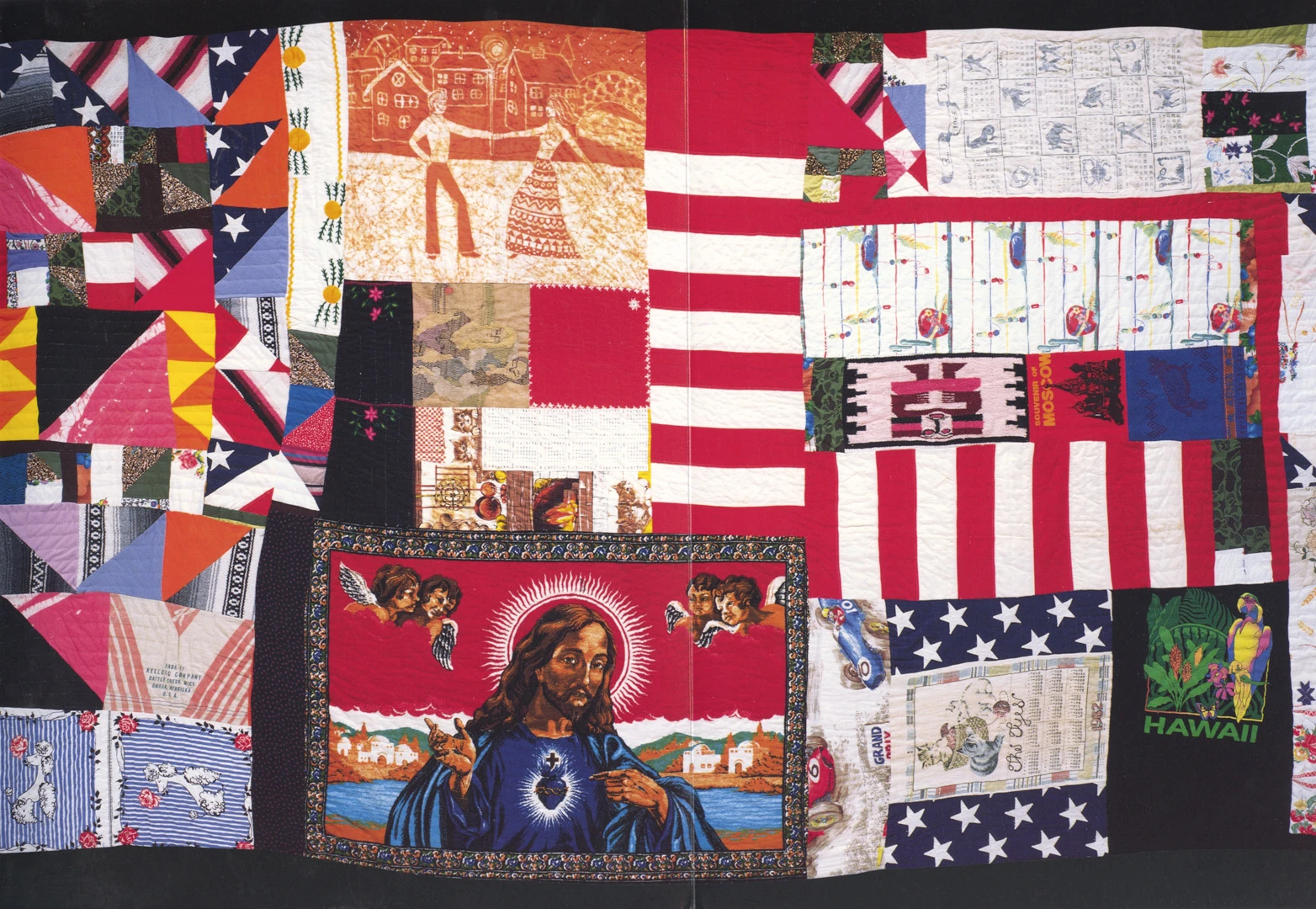

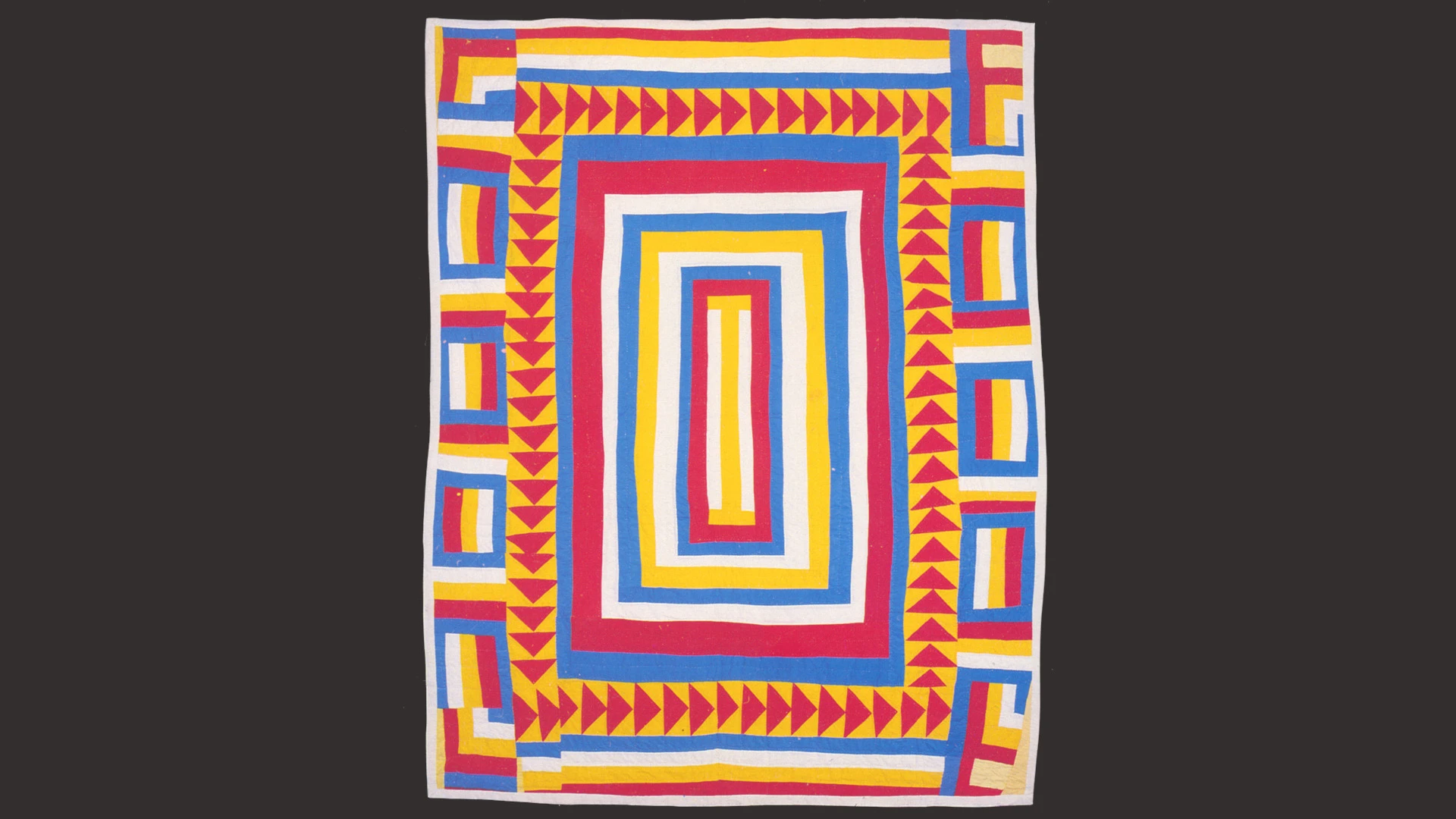

African American quiltmaking is an art that stretches back as far as our forced presence on this country’s soil, and even further than that; African textiles, like the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s sepia-toned Kuba fabric, exist as early forms of the gridded, patchwork quilt. “Quilts have been part of black life in America probably from when some of the first [Africans] came to America and tried to make things to keep themselves warm and, at the same time, took that opportunity to express themselves through color and composition,” Rinder says. These multipurpose fabric histories—each square telling its own story, like a frame in a comic book—were almost always sewn by women. They are one of the only art forms that exist as vivid, tactile illustrations of black female domestic life throughout history.

Rinder says the collection includes quilts going back to the early 20th century, perhaps even the 19th century, including some made by women who were born into slavery. The majority are late-20th century pieces from quiltmakers in the Bay Area who were born in the South. During World War II, the shipyards in Oakland became a destination for scores of African Americans looking to escape the South and migrate elsewhere for work. Naturally, they brought their artistic traditions with them, and soon a black quiltmaking community blossomed in the foggy East Bay.

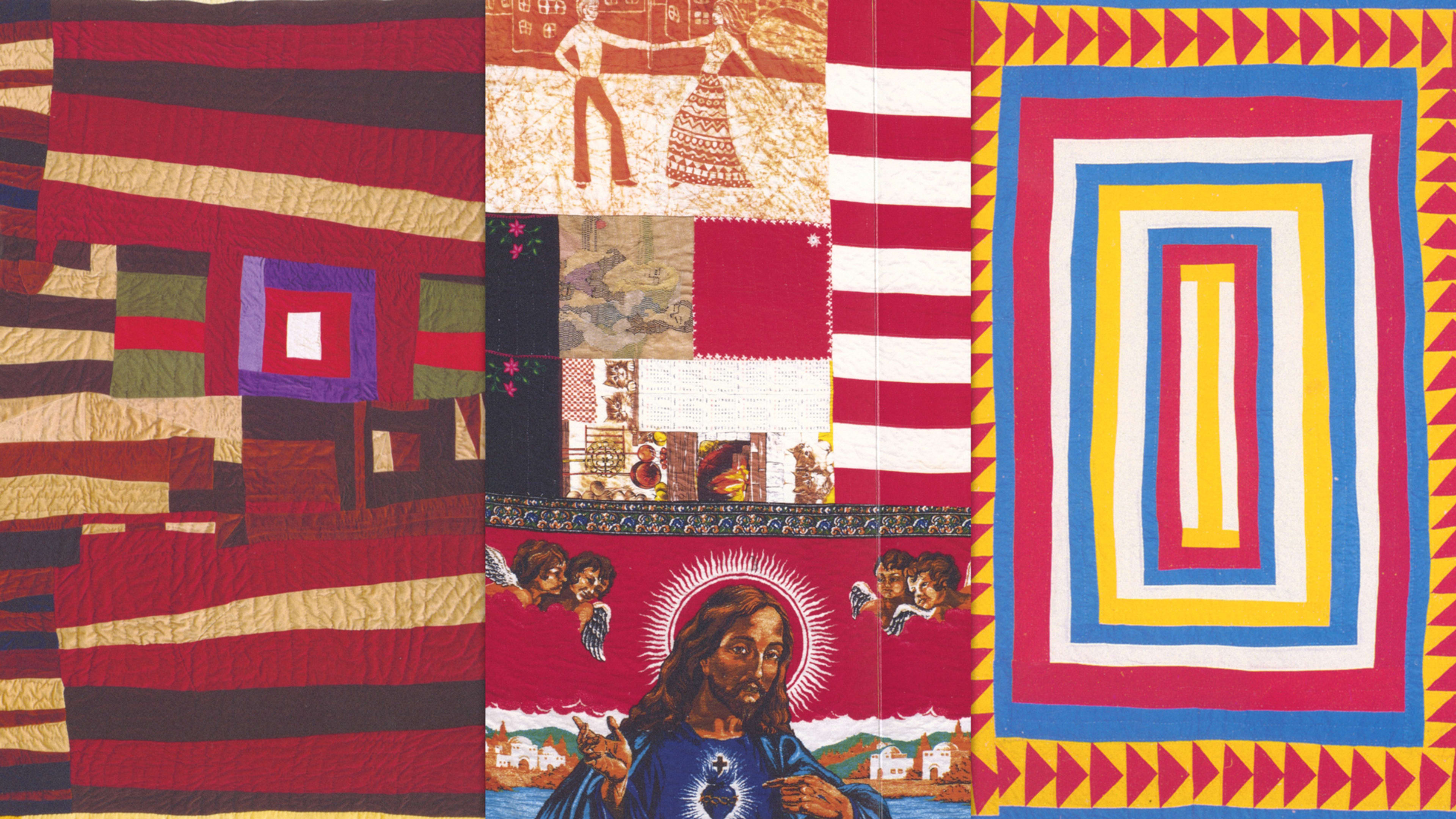

Other quilts in the collection came from the Midwest or other parts of the U.S. Leon received a Fulbright to travel around the country to collect quilts and interview artists, so there’s a broad geographical and historical range in the collection, Rinder says. Many of the artists whose work now joins BAMPFA as part of Leon’s donation—Arbie Williams, Laverne Brackens, Gladys Henry, Sherry Byrd, and Angie Tobias—hail from the postwar, segregated South. Though their styles range vastly, they are united by a central interest in representing the African diaspora and how it adapted to a new environment through color, pattern, and texture.

Next year, Rinder (along with his co-curator Elaine Yau) has a solo exhibition of the work of Rosie Lee Tompkins planned for BAMPFA; it will include a career-spanning 80 of the artist’s 500 quilts, which are now all part of the museum’s permanent collection. Another exhibition, slated for 2022, will feature work from the whole of Leon’s donation, which boasts work from an impressive 400-plus individual artists. In the meantime, the museum is focused on fundraising for storage, conservation, and cataloguing the quilts.

“There’s such wonderful diversity of expression in African American quilts and I personally feel that these quilts have provided an opportunity for a kind of creativity and expression that is kind of on the level of jazz or blues as an expressive medium—just in a different material,” Rinder says. “Instead of sound, it’s fabric and color.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.