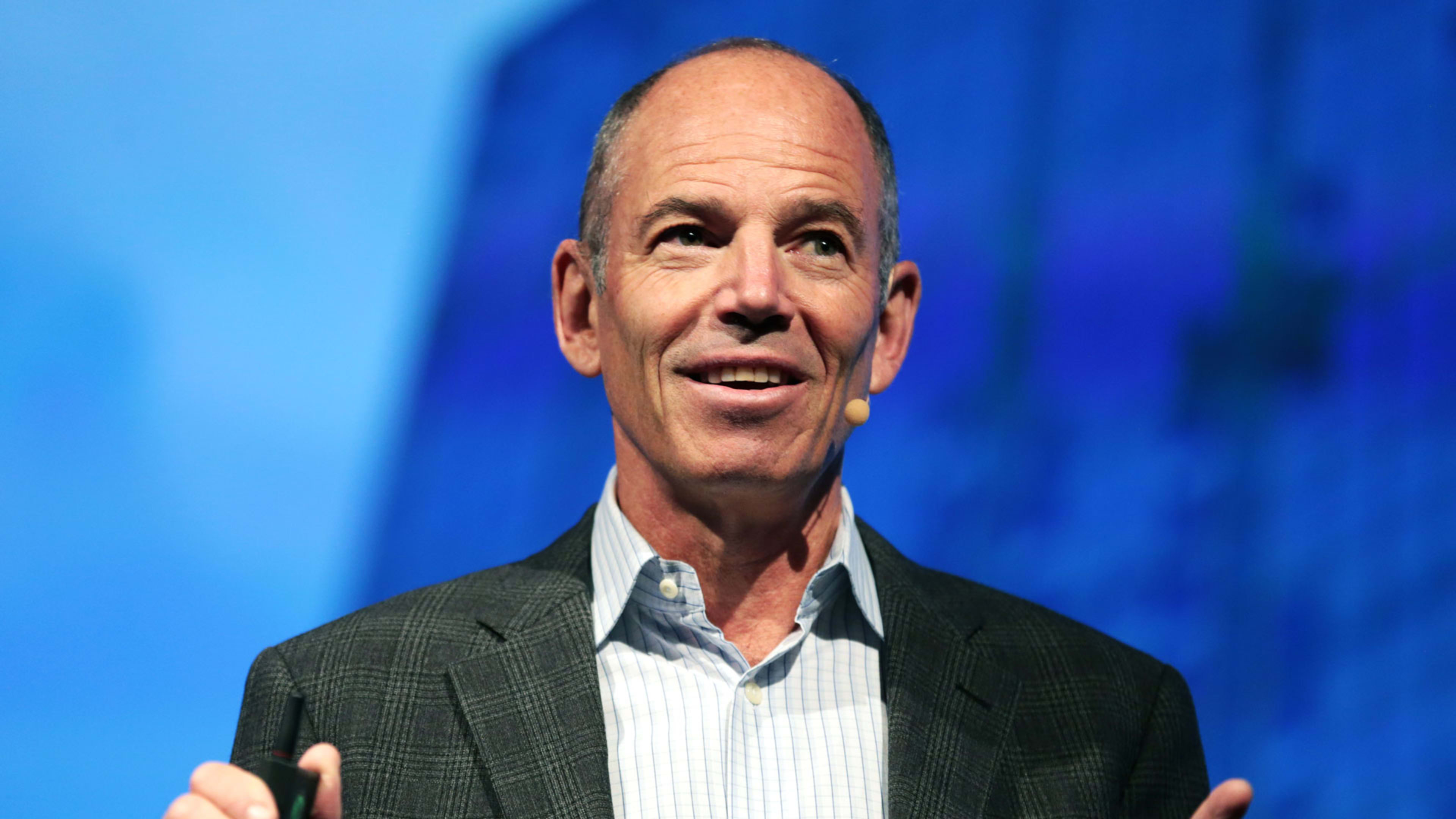

Long before it became the content behemoth that devoured every waking minute of your life, Netflix was a failing DVD rental service barely surviving in the $250/month conference room of a Best Western hotel. It was a miracle that the company made it to the next day, with constant challenges that threatened its bottom line and earned it the condescension of video rental companies like Blockbuster. Cofounder and first CEO Marc Randolph tells the inside story of the company’s growth and triumph in his new book, That Will Never Work: The Birth of Netflix and the Amazing Life of an Idea.

Part of the company’s secret sauce, according to Randolph, is its work culture, which in the late 1990s distinguished it from many startups that reveled in glamorous perks but ignored core values like giving employees freedom and responsibility. Randolph talked to Fast Company about Netflix’s roots, its improbable success, and why he thinks Netflix’s history has prepared it to conquer the future of streaming.

This interview has been edited for clarity and concision.

Fast Company: What did all of Netflix’s streaming rivals misunderstand about the company?

Marc Randolph: For one thing, Netflix started before streaming was even a possibility and certainly glimpsed that this was coming and was acting on it at the beginning. From day one, as you saw in the book, when we were pitching the company, a lot of people were saying, “Oh, that will never work.” And a lot of them were saying that [our DVDs by mail business model] would never work because they believed that, in just a matter of weeks or months, everyone would be downloading these movies or streaming these movies. And we of course knew that eventually that would be true, but we did not know how long that would take, and instead we built a company that would allow us not only to wait but would allow us to build equity and things that would have value at that point. Not just the brand, but building an expertise in helping people find entertainment they love. We never viewed ourselves as a DVD company but as a company that was really trying to help people find things they wanted to watch and that transcended whether they got it on DVD or got it on streaming.

FC: Well, Netflix has found a way to completely dominate its competitors. I’m curious about what they missed that Netflix has been able to tap into, besides maybe having a little bit of a head start?

MR: That’s a huge piece of it. Certainly the fact that we started in 1997 and Disney started in 2019—I think that does make a difference. We have certainly been busy building a company that understands how to give customers what they want for a long time. The other big advantage is that we were a startup. We’ve always been a startup and you have to be scrappy. And I think you [see] that in [my book], That Will Never Work. This was a company where we said it was more important to have a crappy green carpet and the DVDs in a safe than it was to spend on corporate extravagances. I would think that even though Netflix has 7,000 employees now, it still feels the same way. Except they don’t have the green carpet anymore.

FC: That ties into my next question, which is about the company’s DNA and how it shaped its growth and its eventual dominance. Can you touch on some of that?

MR: Certainly. Culture is not what you say, it’s what you do. And a lot of Netflix’s culture springs from the way that [cofounder and CEO Reed Hastings] and I treated each other and how we treated our early employees. And so even though Netflix now is a much, much bigger company, and of course it’s developed all kinds of cultures that are somewhat different from those in the early times, you can certainly see the remnants of how we’d interact back then. You see the focus on the metrics. You see the focus on deep personalization. You see this focus on helping people get the right entertainment at the right time.

Culture is a critical piece of success. And a lot of that stuff was forged early on, and part of what I wanted to get across is where some of that culture came from, where the seeds of freedom and responsibility were planted.

FC: Has it changed from when you were there versus how it’s kind of codified now in the legendary Culture Deck (a 125-slide presentation that outlined the company’s values, expected behaviors, and core philosophy)?

MR: The first caveat, of course, is that I’m no longer there so I don’t see it from the inside. But certainly the things I read and hear about the culture, there are lots of resemblances. However, I acknowledge it’s different. It’s one thing to have a culture that works for 300 people and another one to have that same culture work for 7,000 people. And those things need to change. But it is remarkable how many of them are exactly the same. At the beginning, of course, we never had a strict sense of vacation time. We all worked when we had to, and we all took our Tuesday evening date nights when we had to. And the ultimate thing is getting the work done.

And I think that Netflix now with its no specific vacation policy is a reflection of that. You know, we spent money when we had to but we treated the money at our company like it was our own. And Netflix still has this idea that you treat the company’s money as if it’s your own.

FC: Was that something unique at the time in the tech sector, to have that type of emphasis on how you treat fellow employees? Because obviously the Valley was known for this brutalist work ethic. And it seems like things started to shift a little bit. Was Netflix one of the first ones to really go in that direction?

MR: I don’t know for sure, but I think so. I had some exposure working at larger tech firms. We wanted a place that was different. And I think what happened is that we fought very hard against falling into the norm. When a company gets bigger, when it begins to bring on employees, it naturally goes through this tendency of wanting to control, of wanting to build process—essentially to say not every one of our customers or employees has great judgment.

FC: That’s telling someone, “We don’t have confidence in you,” and that impacts people’s performance, for sure.

MR: And then what happens? Of course you begin driving out all the people who have great judgment. Then you need even more structure and process to avoid people doing silly things. And instead you get the opposite.

There’s a great story about [former Netflix chief talent officer] Patty McCord. We worked at Borland International, a big software company. And we had the typical corporate campus. We had the Olympic-size swimming pool and the big squash courts and the cafeteria and we had a hot tub, of course. And one time Patty and I were walking back from lunch and we saw some engineers soaking in the hot tub. We went over to say hello and they were bitching about the company. And as we walked away, we began saying, “Well, what does this say? People have amazing perks and they’re still complaining.” And it led to this interesting discussion about what really is it that makes people want to come to work and enjoy working someplace. It’s not the beanbag chairs and the nap pods and the beer on tap. It’s being given freedom and responsibility, and we recognized that in building a company, it’s harder to install those things than it is the nap pod.

FC: I would love you to talk about another story in the book, the talks with Jeff Bezos and Amazon. How nerve-racking was it to walk in to talk to Bezos about a possible acquisition?

MR: Well, certainly it was a tremendous mix of emotions as Reed and I were flying up to Amazon. On the one hand, it was tremendously flattering that this pioneer in e-commerce thought that this little company might actually have something to offer. And at the same time, we knew what it was that Jeff Bezos was interested in and it really was uncertain to us about whether we wanted to do it.

Did we want to sell the company at this point? It would have been a nice financial outcome for me . . . If anything, that trip to Amazon and seeing these strange offices was more like a commitment ceremony. It tested our resolve. As we were flying home, we didn’t spend too much time talking about the offer, what the offer might be, or even whether we should accept the offer. We found ourselves naturally drifting to talking about the future, of what we planned to build. And so the decision that no, we weren’t ready to sell, came naturally.

FC: Were you surprised at the offer of between $14 million and $16 million? Did it seem low? Were you expecting more?

MR: To be honest, we weren’t sure what to expect. And the amount was not even the critical piece because we never really got to the point of pressing Jeff or [then Amazon CFO] Joy [Covey] about what the actual offer was or asking for a term sheet. This was really much more of an existential question: Were we prepared to join up with Amazon and end our dream? Or did we want to see this through? And ultimately what we decided was we wanted to see this through.

The other amazing thing was seeing the inside of the Amazon offices and recognizing that a lot of the things that we were doing by instinct . . . well, if it was wrong, then they were doing it wrong too. In other words, this focus on making sure the resources went toward the customer, not to making it cushier for the employees. And it was kind of fun trading startup stories with Jeff Bezos.

FC: Anything that he said that surprised you or stays with you?

MR: I distinctly remember sharing stories about having the bell that rang when the first orders came in. I think his outcome was a little bit better than ours, where our bell ringing did not lead to this fantastic day of launch. It led to a crash. But at least we shared that initial beginning.

FC: Afterwards, when you decided not to make a deal, were they disappointed or not?

MR: No. One of the things that Reed and I talked about on the ride home was that you don’t want to be sticking pins into the 800-pound gorilla. And so even though we opted not to sell, we decided explicitly that we wanted to stay in good graces with them. We thought it was unlikely that Bezos would be foolish enough to enter rental and that it was inevitable that he would enter sales. And we recognized that we were going to have to get out of sales and here’s an opportunity for a potential quid pro quo. And I think the strategy was, let’s just sit tight, let’s stay in their good graces, let’s stay in contact, and then when they announce that they are getting into DVD sales, let’s reach out to them and see if we can strike a deal—which of course we did.

FC: I wanted to ask you about MoviePass CEO and former Netflix executive Mitch Lowe and whether his career post-Netflix—like Redbox and Movie Pass—points to a sort of orthogonal way to compete against Netflix?

MR: [Laughs] Mitch is an amazing guy and I love telling the story of bumping into him standing behind his little card table booth at the Video Association Trade Show and then learning afterwards that he was actually the president of the whole trade organization, which is why I set my sights on wooing him to join this little startup. I immediately recognized he had all of this domain expertise that none of us had. He knew movies. He was the guy who watched movies all day in the video store, then got home and had dinner, and then watched movies all evening with his family. Then, when they went to bed, he watched movies late into the night.

He was a huge guiding force behind this Netflix drive for personalization because he had this native ability to do what we spent a lot of time and money building, which was see somebody walk into a store and by asking just a few questions—what they’ve seen before, what they liked, what they disliked—be able to intuitively match them with a movie that he knew that they would like, and that he had in stock.

And in a sense, the initial interest of us building up personalization was just trying to emulate what Mitch was able to do innately. And it was kind of a nice bookend because at the very beginning, Mitch and I spent countless hours in the car talking about video, and Mitch teaching me the video business. Then at the end of my last project, Netflix was working with Mitch in Las Vegas on our kiosk business, which ended up being successful, which we brought back to Los Gatos and ultimately decided not to go forward with. But Mitch ran with it and it became Redbox. Movie Pass was yet one more extension of that recognition that subscription movies was possibly an idea whose time had come.

FC: When they started putting a lot of money into producing original content, it inspired that SNL skit where a bunch of Netflix execs say yes to every idea and throw money at it: “Sure. Do it!” You weren’t there then, but was there a moment when you thought, “Whoa, guys, this is a little crazy.” That they’re spending so much money on these expensive big productions and maybe three people will watch some of them.

MR: Absolutely not. From the outside, I was saying, Right on. These are all the things that are just continuing reflections of the things that we talked about early, which is making bets on the future regardless of its impact on the past. Recognizing where things are going. You’re saying, this is where the bet should go, not preserving something else. That SNL skit notwithstanding, I knew that every move we made was done with this tremendous focus on testing and metrics and having the data demonstrate what should take place—not arguing, or randomly throwing things at the wall.

FC: Where do you see streaming going? What’s the future of content delivery?

MR: If I knew the answer to that, I’d be much more of a savant than I am.

I think right now we’re at a period of expansion and stabilization rather than deep innovation. Certainly consumers are voting with their time and with their wallets that they like the ability to receive content when they want it and in the forms that they want it. And what we’re seeing, as you mentioned, is many, many companies that are all racing to deliver that.

But as you also know, we’re a long way from being fully built out. If you look at the penetration of all the streaming services combined across the world’s internet population, it’s very small still, right? This is not where we’re going to be seeing a huge advantage, the same types of leaps that took place when we pioneered rental by mail and then used that as a platform to move into delivering movies via bits or wire over the air.

You’re going to see this spreading. And I think the real lesson here is that what’s made this happen is not some innate movie ability of a company like Netflix. It’s the fact that these things we put in place at the very beginning—the flexibility, the culture—allowed us to adapt to changes as they came and ride those things out, to move from selling to be able to drop selling DVDs and move to renting them, from renting them to streaming them, to move to developing our own content. And in the future, who knows, maybe we’ll be beaming movies telepathically into our dental fillings. And as long as that culture and those things that Reed and I started during those very first drives in the car are there, I think Netflix can straddle that divide too.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.