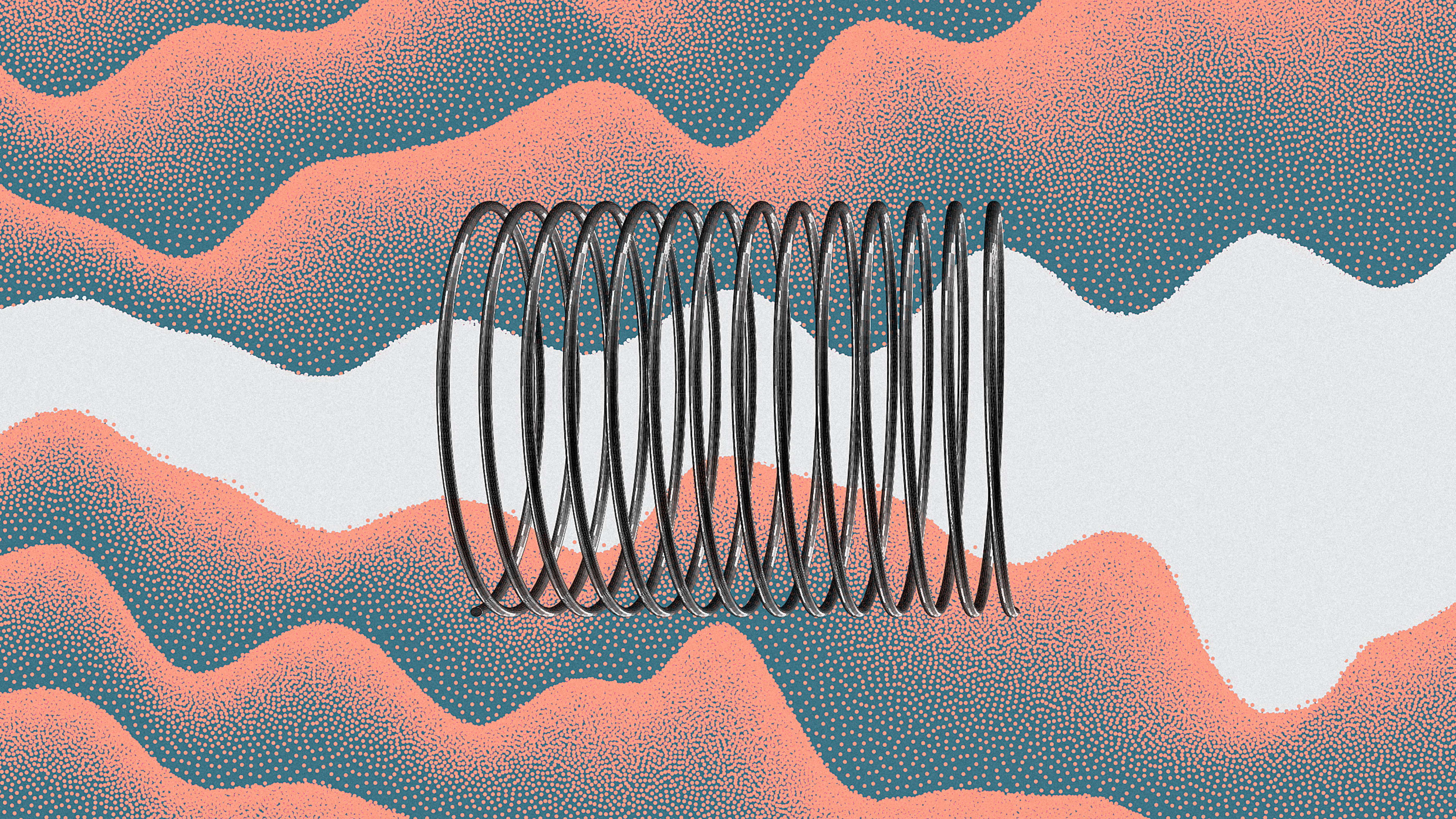

Microplastics—tiny fragments of plastic smaller than 5 millimeters across—are so ubiquitous that plastic is now found in drinking water, Arctic snow, and the deepest part of the ocean. As plastic breaks down, the tiny size makes it even harder to remove from water. But scientists are testing a new method that could safely dissolve it: tiny, spring-shaped magnets.

“By using this technology, we’re able to decompose microplastics completely into carbon dioxide and water,” says Xiaoguang Duan, a chemical engineering research fellow at the University of Adelaide in Australia and one of the authors of a new paper in the journal Matter about the research.

The process uses carbon nanotubes laced with nitrogen that generate reactive chemicals called free radicals, triggering reactions that break down plastic molecules. In the lab, the researchers tested the technology on microplastic beads that are used in toothpaste, facial scrubs, and some other products (these microbeads are now banned in some countries, including the U.S. and U.K., but still used elsewhere). Within eight hours, a significant portion of the plastic had been transformed into harmless compounds. The nanotubes are designed in a spiral shape that helps them stay stable in the process; metal built into the tubes makes it possible to use magnets to remove the nanotubes from water when the work is done and reuse them again later.

In the study, the researchers also tested whether the process created any toxic materials. “It turns out that the degradation products of microplastic are completely harmless, and they can also be used as a carbon source for algae growth,” says Duan. “The microplastics are completely transformed into carbon dioxide or other harmless substances, and they will not cause any adverse or toxic effects to microorganisms or fish or other animals in water.”

The technology is still at a proof-of-concept stage in the lab, and so far, the scientists have only proven that it works with microplastic beads, not other forms of microplastic, such as fragments of plastic water bottles. But there are early signs that this would work more broadly. “We already did some preliminary experiments, and we found that the technology still works for other types of microplastic,” Duan says. The team plans to continue improving the efficiency of the technology and testing toxicity. Eventually, the process could be used in wastewater treatment plants. It’s less likely that it would be used directly in the ocean—though it’s theoretically possible—because of the scale of the problem; even removing larger pieces of plastic trash from the ocean is a Sisyphean task. But it may be able to prevent some microplastic from reaching waterways in the first place.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.