This is the 48th in an exclusive series of 50 articles, one published each day until July 20, exploring the 50th anniversary of the first-ever Moon landing. You can check out 50 Days to the Moon here every day.

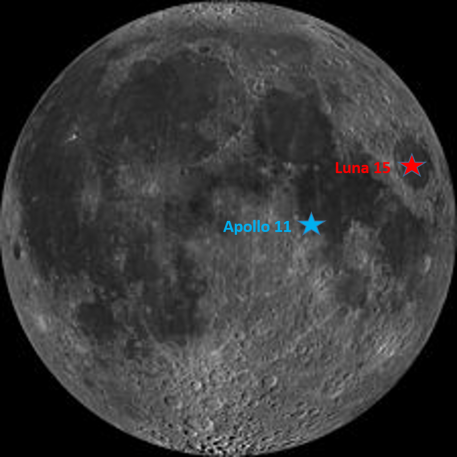

When the Apollo 11 spaceship that carried Michael Collins, Buzz Aldrin, and Neil Armstrong from the Earth to the Moon arrived in lunar orbit on Saturday, July 19, 1969, there was already another spaceship in orbit around the Moon waiting for them. It had arrived two days earlier, from the Soviet Union.

It was certainly no coincidence that with the whole world watching—at the moment when the United States was getting ready to land people on the Moon’s surface—the Russians had decided they, too, ought to have a spacecraft at the Moon.

Luna 15, an unmanned craft, had been launched on Sunday, July 13, and the Russians said it was simply going to “conduct further scientific exploration of the Moon and space near the Moon.”

But from the moment of Luna 15’s launch, U.S. space scientists and NASA officials speculated that it was a “scooping” mission, designed to land on the Moon, extend a robotic arm, scoop up some soil and rocks, and deposit them in a compartment on the spacecraft, which would then zoom back to Earth, bringing home Moon rocks just like Apollo 11 would, and maybe, just maybe, arrive back on Soviet soil with its cargo before the Apollo 11 astronauts could make it back to the United States.

Frank Borman, the commander of the Apollo 8 mission that had orbited the Moon, had just returned from a nine-day goodwill tour of Russia—the first visit by a U.S. astronaut to the Soviet Union—and appeared on the NBC news show Meet the Press the morning of Luna 15’s launch.

NASA, at least publicly, was mostly concerned that Russian communications with Luna 15 might interfere with Apollo 11. In an unprecedented move, NASA asked Borman to call Soviet contacts from his just-finished trip and see if they would supply data on Luna 15. The Soviets promptly sent a telegram—one copy to the White House, one copy to Borman’s home near Houston’s Manned Spacecraft Center—with details of Luna 15’s orbit and assurances that if the spacecraft changed orbits, fresh telegrams would follow.

It was the first time in the 12 years of space travel that the world’s two space programs had communicated directly with each other about spaceflights while they were being flown. NASA said Luna 15 and the Apollo spacecraft would not come anywhere near each other. Armstrong, Aldrin, and Collins, NASA said, would have neither opportunity nor time to look out the window in search of the rival spacecraft.

Luna 15, at least to start, succeeded in making sure the Soviet Union’s space program wasn’t overlooked while Apollo 11 dominated the news worldwide. The Luna 15 mission made the front pages of newspapers around the world. On July 19, 1969, the third day of the Apollo 11 mission, the New York Times published four stories about Luna 15 and published the full text of the telegram from the Russians. Two of those stories were on the front page, including the lead story for the day: “Moscow Says That Luna 15 Won’t Be in Apollo’s Way.” (That day there were only four other stories about Apollo.)

Despite all those stories, no one in the United States knew what Luna 15 was up to. In fact, NASA and the public didn’t find out until later.

Now we know it was a well-planned effort to upstage Apollo 11, or at least to be onstage alongside the U.S. Moon landing, according to documents released and research done since the breakup of the Soviet Union and thanks to historian Asif Siddiqi’s rich and detailed history of the Soviet space program, Challenge to Apollo.

By 1969, the Soviet manned space program had fallen well behind the determined, even relentless effort of the United States. But the Soviet robotic program remained ambitious.

Spurred on in part by the worldwide success and acclaim of Apollo 8 and by the daunting expectation that the Americans would land astronauts on the Moon by the summer of 1969, Russian space scientists had assembled five identical robotic Moon probes. They were designed to fly to the Moon, land, then drill a foot into the Moon’s surface to obtain a soil sample uncontaminated by the lander.

This would be sent back to Earth in a small upper-stage of the probe that would blast off from the Moon, delivering its sample back home by parachute.

No one in Russia was under the impression this would match a landing of American astronauts. But if they could do it before Apollo 11, what had for half a decade been the world’s premier space program would be able to retain a certain pride—and also lay claim to the scientific breakthrough of having first brought samples of the Moon back to Earth.

As Siddiqi points out, it was not lost on the Russians that their lander would have all the more potency if, for some reason, Apollo 11 didn’t succeed.

The first Soviet Moon-scooping spacecraft had been launched, without public announcement, on June 14, 1969, a month before Apollo 11. The fourth stage of its booster rocket failed to ignite, and the probe landed in the Pacific Ocean.

The second attempt—like the first, its timing dictated not only by competition but also by the fixed launch windows related to getting a spaceship to the Moon from the Soviet Union—was Luna 15.

When Luna 15 arrived in lunar orbit on July 17, two days ahead of Apollo 11, Siddiqi says, Russian space officials were surprised “by the ruggedness of the lunar terrain” where it was headed, and that the craft’s altimeter “showed wildly varying readings for the projected landing area.”

As Armstrong and Aldrin stepped out onto the lunar surface, Luna 15 was still swooping around the Moon, her flight controllers back in the Soviet Union trying to find a landing site they had confidence in.

Two hours before Armstrong and Aldrin blasted off from the Moon, Luna 15 fired its retrorockets and aimed for touchdown. The British radio telescope at Jodrell Bank Observatory, presided over by Sir Bernard Lovell, was listening in real time to the transmissions of both Apollo 11 and Luna 15. And Jodrell Bank was the first to report the fate of Luna 15. Its radio signals ended abruptly. “If we don’t get any more signals,” said Lovell, “we will assume it crash-landed.”

The Soviet news agency Tass reported with its classic obtuseness that Luna 15 had “left orbit and reached the Moon’s surface in the preset area.” Its “program of research . . . was completed.”

Despite taking almost a whole extra day to figure out the terrain, Soviet space scientists apparently missed a mountain in the Sea of Crises. On its way to the “preset area,” Luna 15 slammed into the side of that lunar mountain, going 300 miles per hour. (The Russians would successfully land Luna 16 in September 1970, and it would return 101 grams of lunar soil to the Soviet Union.)

At about 1:15 p.m. ET Tuesday, July 22, the Apollo astronauts woke from a 10-hour rest period. Armstrong and Aldrin had blasted off from the Moon about 24 hours earlier, and the three Apollo 11 astronauts were 12 hours into their 60-hour ride back to Earth. As they got started on their day, capcom Bruce McCandless caught them up on the morning news.

About one-third of the way through McCandless’s space newscast, he reported, “Luna 15 is believed to have crashed into the Sea of Crises yesterday after orbiting the Moon 52 times.”

If ever there was a moment that captured the crushing reversal in the performance of the world’s two space programs of the previous decade, that was it: Mission Control, Houston, matter-of-factly reporting the Soviet Union’s somewhat flailing attempt to use a robotic probe to bring home Moon rocks—to the three astronauts currently in possession of 47.5 pounds of them and headed home.

Charles Fishman, who has written for Fast Company since its inception, has spent the past four years researching and writing One Giant Leap, his New York Times best-selling book about how it took 400,000 people, 20,000 companies, and one federal government to get 27 people to the Moon. (You can order it here.)

For each of the next 50 days, we’ll be posting a new story from Fishman—one you’ve likely never heard before—about the first effort to get to the Moon that illuminates both the historical effort and the current ones. New posts will appear here daily as well as be distributed via Fast Company’s social media. (Follow along at #50DaysToTheMoon).

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.