Airplane design has basically remained unchanged for decades. The vast majority of planes are variations on the same basic design: A cigar-shaped body with a cockpit where pilots can see the front of the craft. That form factor may be about to change. Last month, the Dutch airline KLM announced it would fund research into an unconventional, V-shaped aircraft body. And now, a new prototype airplane being developed by aerospace contractor Lockheed Martin for NASA will change the latter.

The plane is called the X-59, and its design aims to greatly reduce the supersonic “boom,” the loud explosive noise that airplanes cause when they break the speed of sound. This noise has been one of the barriers facing commercial supersonic airplanes (along with fuel efficiency and expensive heat-resistant construction materials like titanium), which is why airplanes like the now-retired Concorde were only allowed to go over Mach 1—the speed of sound—while flying over the ocean.

The angle is so shallow, in fact, that it’s impossible to install any forward-facing glass for the pilot to see ahead. Instead, NASA and Lockheed Martin decided to put a large 4K monitor connected to a video system called XVS (eXternal Visibility System). This computer-vision system stitches together the input from two external video cameras and combines it with 3D synthetic terrain data to deliver an augmented reality version of what lies ahead of the pilot. The cockpit also has side windows so pilots can still see the horizon line—at least on a clear day, which is why airplanes have attitude indicators that give the pilot a graphical representation of Earth’s horizon when they can’t see because of low-visibility weather conditions.

The road to window-less cockpits

It’s an innovative and bold design for sure, but this is not the first time that aircraft designers have considered “windowless” cockpits.

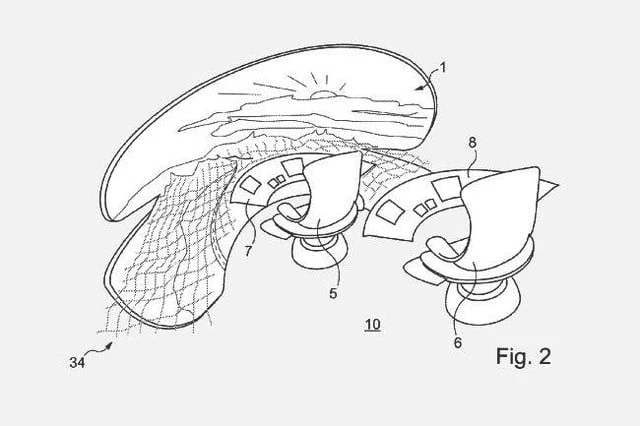

Five years ago, Airbus patented completely windowless cockpits, which the company has been working on for years. The patent described an array of cameras that captured real-time video that could be projected on a giant display that wraps around the entire cockpit, effectively making it “transparent” and providing a panoramic, unobstructed view of the horizon. Couple those visible light cameras with infrared cameras that can see at night and through clouds, and you get a perfect cockpit—at least in theory.

https://youtu.be/xRbQXL1oMqY

But combat pilots can still disconnect these systems and fly just by looking out the windows of their cockpits. Would a commercial pilot accept the idea of a windowless cockpit with no alternative to a display, no matter how advanced the video technology is? In the case of an experimental plane like the X-59, it comes as a given in the test pilot’s pay. But on a commercial or combat plane, pilots may be more hesitant. For the time being, anyway.

There’s obviously the matter of potential electronics failure: If the screen fails, there is no backup in a cockpit like the X-59’s. Sadly, recent airplane catastrophes have proven that depending on electronics alone to control an airplane may be too much of a risky proposition.

“We Want A Window”

Pilots could probably still fly a plane by looking at the instrumentation—after all, they already do that when the weather is bad—but they won’t be as comfortable without a visual reference. In one famous case, pilots have even revolted against the idea of a windowless aircraft: The Mercury Seven, which is what the media named the astronauts who flew and helped design America’s first space capsule, Project Mercury, famously rejected the idea. They argued that, as pilots, they needed to see what was in front of them. They were not monkeys getting blindingly shot into space, they reasoned, and one of the must-have, non-negotiable design requirements for a cockpit was for it to have windows.

Of course, there were no video screens in the cockpit back then. But, at least for the time being, it’s hard to imagine most pilots—or the FAA and passengers for that matter—accepting windowless cockpits. But over the coming years, as the technologies introduced by the X-59 mature and radically new airplane designs come into service, that may change. Eventually, unmanned airplanes may even change the practical need for windows and the public’s perception of their necessity, too.

Another issue could push windowless aircraft into normalcy, too: The push to launch new manned spacecraft, whether piloted by astronauts or computers. In space, windows only complicate design, needlessly introducing points of failure. In the International Space Station, the Cupola observation window remains covered by shutters until the astronauts need to use it.

Our romantic need to see where we are going with our own eyes, rather than through a virtual interface, may eventually be forgotten in the name of simplicity and safety. As a wannabe astronaut myself, I’m just glad I won’t be around to see it.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.