Today, electronics are made out of heavy metals and rare earth elements, which have spawned a global mining operation that’s bad for the environment and often exploitative toward the people who work in the mines. But an MIT researcher is proposing a new way of thinking about circuits: Instead of always relying on traditional materials to make them, what if instead we looked toward some of planet’s oldest sensors?

“Plants are these wonderful things. They’re billion-year evolutionary machines,” says Harpreet Sareen, an assistant professor at the Parsons School of Design and an affiliate researcher at the MIT Media Lab. “They have naturally occurring signals, they change their color, their orientation, the position of their flowers. And they can sense things around them. We were looking at how these sensing mechanisms are all things we try to do in our electronics.”

[Image: Harpreet Sareen]

Through two new projects, Sareen has created novel ways to transform plants into interfaces. The work, which was published in May for the annual ACM Computer Human Interaction conference, builds on a previous project in which Sareen turned plants into sensors—with leaves that could sense motion and send a signal to a computer.

[Image: Harpreet Sareen]

But now, with a new project called Phytoactuators, he has developed a way to complete the loop and transmit an electronic signal back to a Venus Flytrap or a Mimosa Pudica—so that the plant itself can act like a notification device. When a user completes an action on the computer screen, like clicking a button, it triggers the jaws of the Venus Flytrap to snap shut. “Our vision is to have this layer of digital interaction within the plants themselves so we can not only sense signals through them, but also connect our digital responses with the plant’s responses,” Sareen says.

This could be used for what Sareen calls “soft notifications.” For instance, if a package arrives at your house, tracking software could send a message to your houseplant to retract its leaves, letting you know your delivery is on your front porch. “These [soft notifications] do not provide cognitive overload,” Sareen says. “This does the job of letting us know that something has changed and we don’t have to explicitly focus on [it].”

But Sareen has a far bigger ambition than turning Mimosa Pudicas into just another interface in your house. He also wants to build circuits inside them, embedding miniature computers into their leaves.

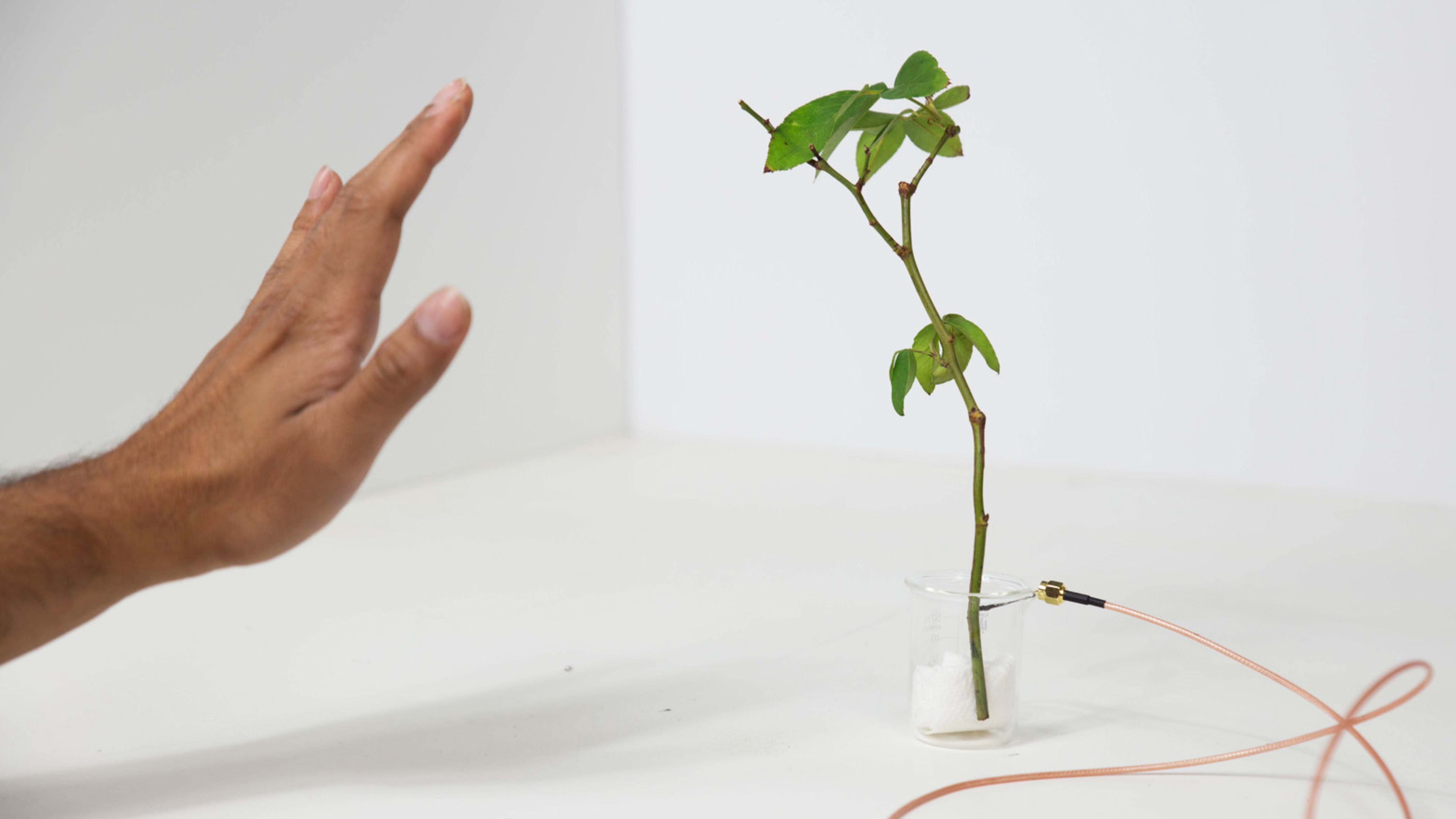

His second new project, Planta Digitalis, is the first step toward that lofty goal. Sareen and his team were able to embed a conductive wire inside the stem of a rose plant. To do so, they created a chemical mixture that is organic, water soluble, conductive, and most importantly, wouldn’t hurt the plant. They dissolved these “liquid electronics” in water, and then placed a rose cutting in the water for a few days. Over time, the rose drew the chemical up inside its stem, essentially creating a trail of conductive chemicals within its tissues. The rose was connected externally to a computer. Then, Sareen could turn the rose into a motion sensor by shooting high-frequency signals up the wire; any fluctuations in the frequency indicated that something was moving nearby.

Sareen thinks this kind of cyborg botany could replace sensors in our homes. For instance, why use a traditional motion sensor if you could have your plant do the work for you (while also providing all the other benefits of being around greenery)? He also envisions networking plants together in natural preserves so that they can count how many animals pass by them, with the goal of tracking the health of ecosystems. Within agriculture, connected plants could inform farmers when they need more water. Next, Sareen is working on using another natural capability of plants—water absorption—to act as detectors of toxins in water sources.

Because plants are self-powering and self-repairing, Sareen hopes to integrate these features with modern electronics. And along the way toward hybridization, he hopes that scientists will find more sustainable ways to harmonize human technology with the natural world. “We are at a point where we understand biology to an extent…We also understand electronics enough where we can start to… design these things together,” Sareen says. “This is only the starting of it.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.