In March, a London-based human rights lawyer started receiving video calls from unknown numbers on Facebook’s popular messaging app WhatsApp. Once, he answered but no one was there. “It was suspicious because it would ring a few times and stop,” says the lawyer, who requested anonymity because of the nature of his work. “And usually, nobody really calls me using video.”

The lawyer didn’t know it, but the calls were part of a sophisticated attack–a way for a hacker to pull up the entire contents of his phone without even him answering the call. Still, wary of a possible hack, the lawyer contacted researchers at digital watchdog Citizen Lab, who proceeded to look into the mysterious calls.

WhatsApp independently discovered the vulnerability in early May, and began making fixes and notifying human rights groups last week, before issuing an update for its 1.5 billion users last Monday. The Facebook-owned company also offered a thinly-veiled description of the suspect: spyware made by the Israeli-based cyberattack firm NSO Group.

NSO says it only sells its spyware, known as Pegasus, to government customers approved by Israel for “the sole purpose of fighting crime and terror.” But Pegasus has been implicated in surveillance of dozens of political dissidents, human rights advocates, and journalists in Mexico, the Middle East, Asia, and Europe. Saudi critic Jamal Khashoggi, the victim of an assassination by Saudi agents at the country’s Turkish consulate, was allegedly tracked using Pegasus infections on the phones of his friends.

Now, as researchers scramble to determine the number of WhatsApp targets–and as NSO’s owners repeat their pledges to halt abuse of the spyware–the company is facing new resistance from watchdogs, investors, and Facebook.

Lawsuits and investor questions

A lawsuit filed last week at the District Court of Tel Aviv by a group of Israeli citizens aims to revoke NSO Group’s export license, arguing that the country’s Ministry of Defense has “put human rights at risk by allowing NSO to continue exporting its products.”

The U.K. lawyer, who continued to receive mysterious WhatsApp calls as late as last Sunday, is not cited in the new legal claim, but he is currently assisting lawsuits against NSO involving targets in Mexico and a Saudi activist living in Canada. Another suit is being brought against NSO-affiliated entities in Cyprus.

Asked about potential legal measures Facebook could take against NSO, a spokesperson for WhatsApp said the company is reviewing its options. Facebook also disclosed the breach to the U.S. Department of Justice last week. A Justice Dept. spokesman told Fast Company that the agency was aware of the issue but declined to comment.

At least one large investor is also asking questions. The South Yorkshire Pension Authority, a U.K. public sector fund that has invested in Novalpina Capital, the London-based private equity fund that is NSO’s majority owner, will meet with Novalpina next week to seek assurances about its oversight of the spyware maker, the Wall Street Journal reported.

Pension funds for Oregon and Alaska, which are also Novalpina investors, did not immediately respond to a request for comment from Fast Company, which first reported the pension funds’ investments in March. The Oregon Public Employees Retirement System invested $232 million in Novalpina in 2017, and previously invested $250 million in Francisco Partners, the U.S.-based private equity firm that formerly owned NSO. Novalpina bought Francisco’s stake in NSO in February at a reported valuation of $1 billion, with help from New York investment bank Jefferies.

Facebook’s “unprecedented” response

Novalpina has promised Amnesty International and a group of other human rights groups that it would bring more oversight and transparency to sales of NSO’s software. In a May 15 letter, it denounced “any form of misuse by any government, agency or individual,” attacks on human rights campaigners, “and we particularly condemn without hesitation any such misuse directed at people who are vulnerable simply as a consequence of their commitment to report on, speak out for or defend human rights,” Novalpina wrote in the letter. It was the second letter Novalpina has sent to the groups since it acquired NSO, and was signed by Novalpina’s founder and CEO Stephen Peel.

NSO, which also goes by the name Q Cyber Technologies, said in a statement that it relies upon “a rigorous licensing and vetting process” for government uses of its tools, and investigates “any credible allegations of misuse and if necessary, we take action, including shutting down the system.” The company says it does not actually operate the spyware for its customers, each of whom may pay millions of dollars per installation.

Danna Ingleton, deputy program director at Amnesty Tech, says that despite Novalpina’s commitment to bring NSO in line with human rights principles, the spyware company has repeatedly dismissed evidence of abusive attacks as inaccurate, or claimed that they were carried out in accordance with local laws.

“NSO have again and again demonstrated their intent to avoid responsibility for the way their software is used,” but “without direct involvement of the Israeli MOD [Ministry of Defense] and DECA [Defense Export Controls Agency], we cannot expect them to conform to Novalpina’s commitment,” she said.

Before it issued a fix last Monday, WhatsApp engineers in San Francisco and London began patching the vulnerability and alerted an unspecified number of targeted users, human rights groups, and researchers at Citizen Lab, the Financial Times first reported.

The WhatsApp spokesperson said it was too soon to say how many other people it knew had been targeted through the exploit, and that WhatsApp may ultimately be limited in what it can learn about the targeting of the U.K. lawyer or any other victims.

“We’d rather this had never have happened, but we’re hoping to contribute to this documentation of what this exploit is,” the WhatsApp spokesperson said. “We’re deeply concerned with these tools existing and certainly the way they’ve been used. Our concern is with the human rights organization and the victims of the attack. It will take some time to piece together, but we hope to be able to help do that.”

The attack was sophisticated, but it also relied on one of the oldest hacking tricks in the book, a buffer overflow: If you can inject more code into an app’s memory than it can handle, the extra data overflows into adjacent memory, overwriting that data and creating an attack vector. In an advisory, Facebook said that vulnerability “allowed remote code execution via specially crafted series of SRTCP packets sent to a target phone number.”

Neither WhatsApp nor Facebook publicly named NSO, instead announcing that the attack “has all the hallmarks of a private company known to work with governments to deliver spyware that reportedly takes over the functions of mobile phone operating systems.” But John Scott-Railton, a senior researcher at Citizen Lab, a digital watchdog at the University of Toronto that has studied NSO for years, said WhatsApp’s very public response was “unprecedented.”

“They sent an exceptionally strong signal by basically making it very clear that they think they know who it is, and by getting in touch with human rights groups before its announcement,” he says. “That, as far as I’m concerned, is pretty much unprecedented and is a very interesting indication that big platforms have really run out of patience with this industry that sells offensive cybersecurity like this.”

Related: The shadowy firm blamed for tracking Jamal Khashoggi launches a Google ad blitz

When a version of the spyware was first identified by researchers at Citizen Lab in 2016, Apple issued a software update to close the vulnerability, but the company neither specified the reason or the culprit, nor did it contact human rights groups.

In 2017, after an investigation with security company Lookout, Google said it found a “sophisticated” piece of spyware on “a few dozen” smartphones in 11 countries, predominantly in Israel, Mexico, Georgia, and Turkey, and contacted impacted users. In a post on its Android Developers Blog at the time, Google said the spyware is “believed to be created by NSO Group Technologies, specializing in the creation and sale of software and infrastructure for targeted attacks.”

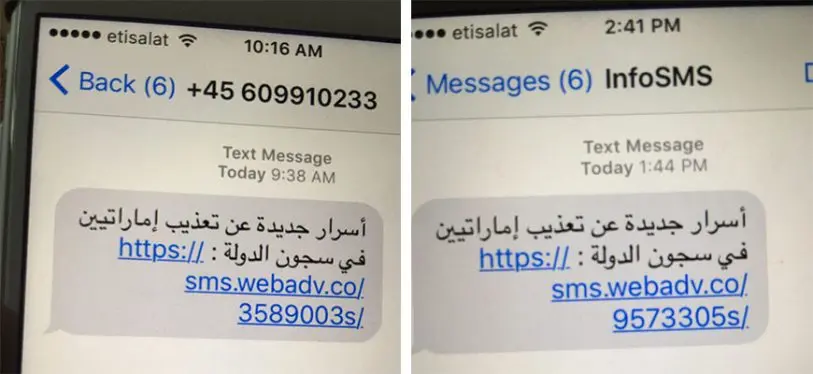

People studying or litigating against NSO have also become the apparent targets of surveillance. Two researchers at Citizen Lab and lawyers involved in cases against NSO have been targeted by mysterious investigators affiliated with Black Cube, an Israeli private intelligence firm implicated in surveillance on accusers of the Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein. NSO and Black Cube have denied any involvement.

Effort to halt NSO’s exports

The new legal petition seeking to withdraw NSO’s export license is being filed by an Israeli lawyer on behalf of 30 Israeli citizens. The petitioners are either members or supporters of Amnesty Israel or members of the human rights community in Israel. In supporting testimony, Amnesty cited an attempted cyberattack last year on one of its members and wrote that its staff “have an ongoing and well-founded fear they may continue to be targeted and ultimately surveilled.”

Amnesty’s Ingleton, who authored the testimony at the center of the new lawsuit, says that Israeli authorities “have not transparently addressed these problematic exports, and have refused to take action on export licenses that have clearly resulted in human rights abuses, and the [Ministry of Defense] must be forced to enforce existing law on NSO.”

Related: Israeli cyberweapon targeted the widow of a slain Mexican journalist

Ingleton says that one major obstacle in legal cases against NSO is the specter of gag orders issued by the Israeli court, which forbid media coverage of the proceedings, and can hinder other lawyers, civil society organizations, and the public from learning about the cases. Gag orders related to national security have already been imposed on the two civil cases being brought on behalf of Mexican and Canadian victims.

Amnesty is also examining other approaches to rein in NSO’s spyware, says Ingleton. “It has been difficult to get accountability for exposed cases of target and attack, and our previous asks to the MOD around this have not resulted in satisfactory answers so we did feel [the petition] was the next logical step to stopping these violations,” she says. “And though the case deals with the MOD, and therefore the state responsibility, we are still keen to keep exploring other avenues for getting justice for past attacks and preventing further attacks.”

Contact this reporter via Signal or WhatsApp at +1 (323) 317-4511, email at djpangburn at protonmail.com, or Twitter DM at @djpangburn.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.