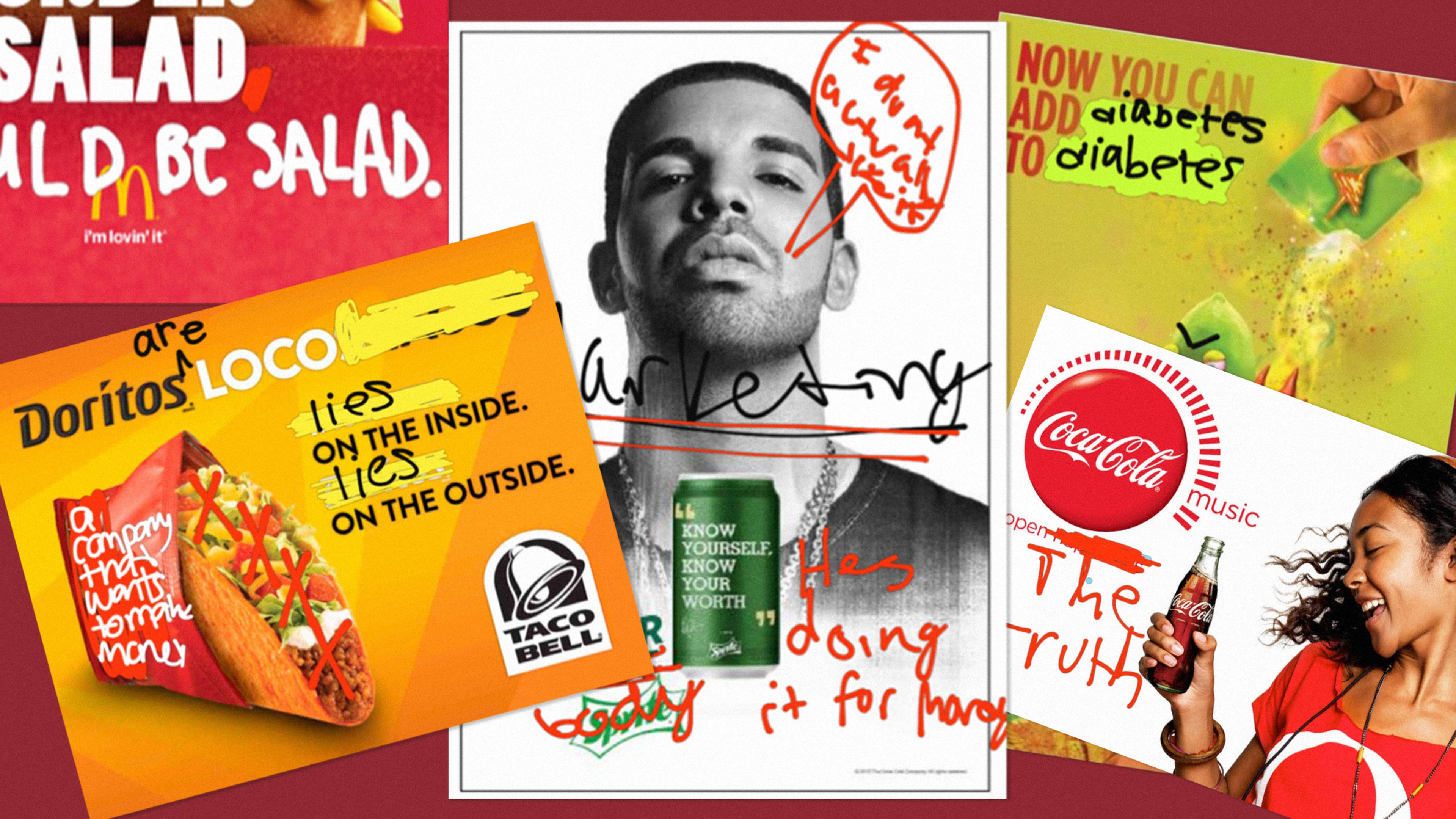

Before it was defaced, the original McDonald’s advertisement featured a towering Big Mac with the all-caps message “THE THING YOU WANT WHEN YOU ORDER SALAD” superimposed over it. Then someone scribbled in an extra clause. It now reads: “THE THING YOU WANT WHEN YOU ORDER SALAD SHOULD BE SALAD,” with the graffiti covering up a golden arches logo.

The most compelling part of the defaced ad though isn’t its message, it’s who drew it and why: an eighth grader at a Texas middle school inspired by a new kind of classroom education that appears to be turning kids against unhealthy messages from fast-food companies and junk food manufacturers. Instead of becoming a lifelong McDonald’s customer, the student is now thinking more critically about what they put in their body.

It’s all part of a new study in the journal Nature Human Behaviour, which found that sharing nutritional information in an investigative journalism format can be more impactful than traditional teaching methods (like sharing the calorie counts of some bad options versus healthier ones)–especially when kids are allowed to rewrite ads after they understand the manipulative tactics behind them.

In an experiment involving more than 350 eighth graders at a Texas school, half of the kids were offered lessons highlighting how the food industry methodically engineers foods that are both bad for us and incredibly addictive–and then often targets children and low-income people with their ads. (That information came from journalist Michael Moss’s book Salt, Sugar, Fat.) The other half of the class was offered lessons about nutritional choices similar to what’s available in traditional middle school textbooks and on the the federal government’s healthy eating education hub Myplate.gov.

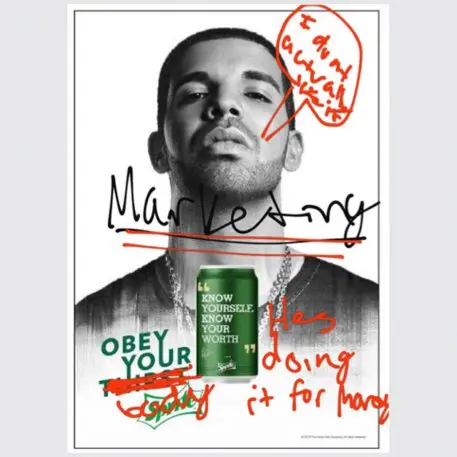

The kids who learned about the food industry then played a tablet-based game called Make It True that gave them a chance to draw directly on conventional advertisements with some of their own additions or corrections. The conventionally educated kids played a different tablet game that involved figuring out how long it might take to burn off the calories of different foods.

“What was really revolutionary about that was it was the first time that nonsmoking was depicted as the rebellious choice,” says lead author Christopher Bryan, a behavioral scientist at University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business. “We thought a similar approach could work for getting kids to adopt healthy eating habits.”

Booth developed the idea with psychologist David Yeager from University of Texas at Austin and Cintia Hinojosa, a doctoral student at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. As the study notes, their findings are important because they could be applied universally. The work builds on an earlier study from 2016, in which the researchers used similar teaching methods–minus the gameplay component–to show an immediate payoff: The day after exposure, kids ordered more healthful options for a school-provided snack pack, the traditional reward for completing state testing.

The bigger question was if such habits could be sustained. The graffiti game may help with that, and not just because it feels rebellious. “We thought, ‘Well, what if we could change how kids perceive the food ads that they see?'” Bryan says. “So instead of seeing [those ads] as tempting inducements to eat junk food, they serve as reminders of how the food industry is trying to manipulate them and other vulnerable groups. Then they might even serve as boosters of our treatment rather than undermining it.”

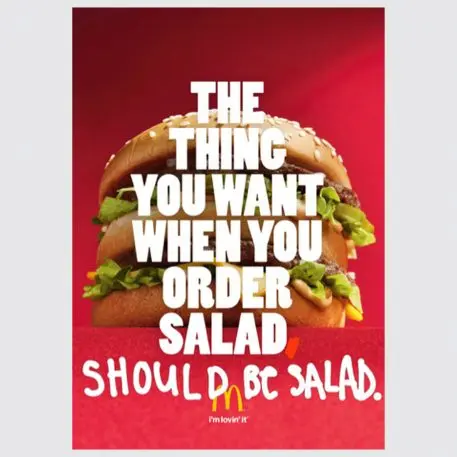

For instance, there’s a Sprite ad featuring the rapper Drake and a soda can embossed with the inspirational message to “KNOW YOURSELF, KNOW YOUR WORTH.” In the study, someone drew a speech bubble beside the rapper’s face to make him appear to say, “I do not actually like it.” Other changes include altering Sprite’s iconic tagline from “Obey Your Thirst” to “Obey Your Body,” alongside a disclaimer about Drake “doing it for money,” and just scribbling “Marketing” with double underlines across the entire ad. The idea is that every time kids see something similar, they’ll now be mentally correcting it. (We’ve asked the companies whose ads were used for comment and will update this story if we hear back.)

When researchers checked back in two weeks, and again at three months, both boys and girls exposed to the investigative format consistently rated ads for unhealthy food choices more negatively and images of healthier ones like fruits and vegetables more positively than those in the more standardized group. What’s more, an anonymized analysis of school cafeteria records showed that boys reduced their purchases of unhealthy snacks and drinks by 31% during that time.

When it came to snack purchasing habits, girls actually shifted their behavior after exposure to both types of education. “We didn’t expect traditional health education to be effective on anybody,” Bryan says. “But I think what we were forgetting is that traditional health education mentions things like calories that can trigger the societal pressures that girls of that age face very strongly to be thin.” While this line of thinking is purely speculative, it might explain the gender variance. If so, Bryan suggests that it could mean the investigative method has the same benefits for women as basic nutritional education–but lowers the risk of body shaming.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.