In the middle of a construction site on the shores of the Toronto waterfront, there’s a bright blue building with a series of cartoon-like characters drawn on its walls, gesturing visitors toward the front door. This is 307, the name for the Toronto office of Alphabet-owned urban design company Sidewalk Labs.

Sidewalk worked with architecture firm Lebel & Bouliane and interaction design studio Daily Tous Les Jours to create a portion of the office that will be open to the public permanently, once a week, as a showcase for Sidewalk’s estimated billion-dollar gamble: Quayside, a 12-acre smart neighborhood that Sidewalk Labs is developing in partnership with the government nonprofit Waterfront Toronto.

The project is controversial. Sidewalk’s plans for the area include a neighborhood-wide digital infrastructure that will collect data about congestion and other elements of urban life, and privacy experts are worried: The former Ontario privacy commissioner who was an adviser to Sidewalk Labs resigned in October, citing fears that even though Sidewalk promised to anonymize people’s data, it couldn’t guarantee that other groups participating in the project would do the same. (Sidewalk then proposed that all the data it plans to collect be stored in a “Civic Data Trust” that no one entity owns.) The debate makes 307 more than an office: It also serves as a marketing tool to sell Toronto’s citizens on the project and make them feel like they’re part of the planning process.

Tools for gathering crucial feedback

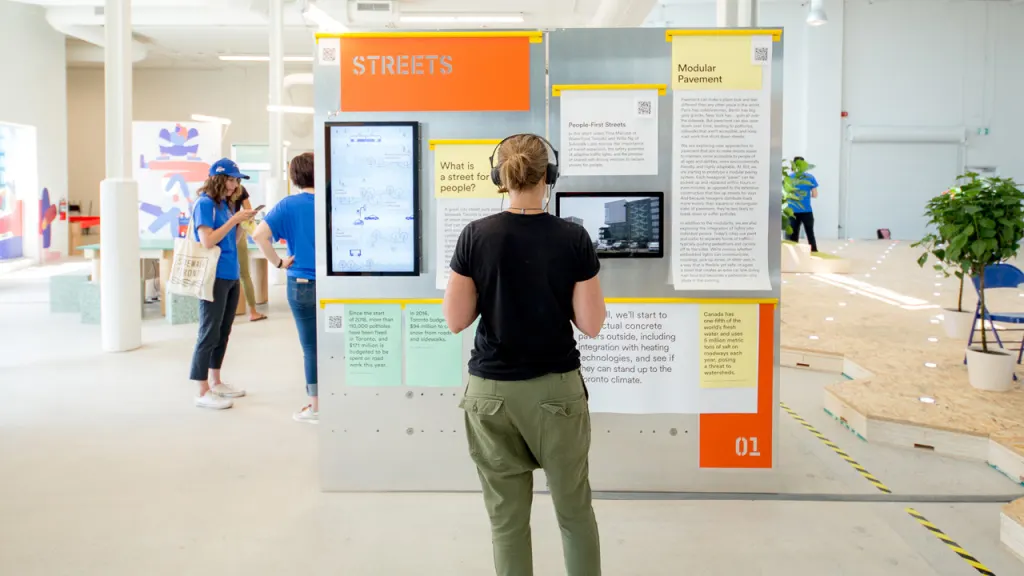

To convince the public to come to an area of Toronto that rarely gets foot traffic, Sidewalk turned a public area near the reception desk within its office into an urban design exhibition. There are installations that provide practical information about Sidewalk’s plans (like a table that focuses on explaining what a smart city is), interactive games that help explain the urban design process, and prototypes of different potential streetscapes. One game, called “On the Streets,” allows people to propose different ways that Sidewalk could use technology to improve the streets, via Mad Libs-style cards. A card might read: “A street light ________ could ________.” Visitors might fill it in to read: “A street light that knows when it’s raining could change its timing accordingly,” or “A street light could detect when someone is crossing the street could change the light to red.” The idea is to get people’s feedback on what they want to see in smart cities in general.

One particularly useful tool for gathering feedback has been a generative mapping game that’s built on top of the actual urban design tool that Sidewalk Labs designed with help from Daily Tous Les Jours and KPF Urban Interface. To make it accessible to the public, Daily Tous Les Jours put a simpler interface on an urban data analytics platform and turned it into a game that lets visitors play around with the neighborhood of Quayside. Visitors can twist a series of dials below the screen that represent things like public space, density, and views of the water to alter those parameters in the virtual neighborhood. There’s also a happy face and a sad face feedback icon so visitors can quickly express their feelings about the urban designs they dream up using the tool.

Jesse Shapins, director of public realm and 307 at Sidewalk Labs, said that this tool has helped start important conversations with visitors. Recently, a family that lived just outside the borders of Toronto came to visit 307. Shapins spoke to the family after they played with the generative design tool, and they told him how originally they’d thought that the ideal neighborhood would be all single-family houses, but by playing with the tool, they’d come to see that it was possible to preserve green spaces and views of the water while still having more dense housing–important since Toronto has a housing shortage.

“That was really interesting: how an ordinary citizen grappled with the trade-off and came to understand some of the benefits of greater density,” Shapins says. “In general, the feedback [from the generative design tool] is that people really care about relationships to parks and the water, to preserve as much open space, views, and access to the water as possible, but people aren’t opposed to density.”

307 has been open for a little over six months, and so far, these interactive experiences as well as events the Sidewalk team has hosted in the space have generated enough feedback to shape the draft plan that Sidewalk released in late November.

Shapins says that through feedback cards and conversations at 307’s open hours and events, many residents have raised the issue of affordable housing as their biggest concern for the city’s future–which Sidewalk tried to address in the draft plan. Of the approximately 2,500 units Sidewalk plans to build in the new neighborhood, half of them will be condos, and half will be rentals–a decision that Shapins says came directly from resident feedback, since condos make up most new housing built in the city. Similarly, the development team is planning for 5% of housing to be shared equity, where people who can’t afford a down payment in full can still contribute to building equity in their home–another decision influenced by feedback from the community. 40% of the 2,500 units will be below-market housing, with half of those units being affordable housing and the other half being middle-income housing.

Hands-on learning

Another element of 307’s lab space is room to build actual prototypes. For instance, Sidewalk built a prototype for a curbless streetscape that’s made up of different types of pavers, or modular pieces that can fit together to form the surface of the street. Some of the pavers can be heated, while others have lights to signal different uses at different times. To do some usability testing, Sidewalk brought in students from the Inclusive Design Research Center at OCAD University. One of their suggestions? To increase the size of the pavers so that someone in a wheelchair or mobility device could move down the street without going over the small seams in between the pavers, a small design detail that could improve stability and comfort. Shapins says this feedback will be incorporated into more paving prototypes in the future.

307 has become so important to the project that Shapins says Sidewalk is considering building a space like it in the future neighborhood. “We believe it’s an important part of community life to have places for people to gather and for experimentation to take place,” he says.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.