In 2009, when James Mitchell was three years into his career at Facebook and first stepped into a role to help police its content for policy violations, the notion that the fate of democracy itself might eventually hang in the balance would have seemed absurd. Back then, the world was still getting its head around the idea that Facebook could be a potent tool for political organizing at all—a novel scenario that had been demonstrated the previous year by Barack Obama’s winningly net-savvy campaign for the presidency.

Today, Mitchell is the company’s director of risk and response, overseeing “how we make decisions around abusive content, how we keep users safe, how we grow our teams at scale to make a lot of these complex decisions,” he says. The issues his team confronts are often freighted with political import, whether they involve the spreading of hate speech in Myanmar or a fraudulent account posing as senior Senator Jon Tester (D-MT).

Mitchell is hardly shouldering this responsibility alone. As the U.S. midterm elections approached, I spoke with him as well as news feed product manager Tessa Lyons, director of product management Rob Leathern, and head of cybersecurity policy Nathaniel Gleicher. Along with charging executives across the country with various aspects of election-related security, the company has staffed up with 3,000 to 4,000 content moderators devoted specifically to eyeballing political content around the world—a meaningful chunk of the 20,000 employees devoted to safety and security whom CEO Mark Zuckerberg promised to have on board by the end of this year, a goal the company says it’s met.

Beyond all that hiring, Facebook has also revised policies, built software, and wrangled data. In the case of its response to the use of political ads for nefarious purposes, it’s done all three, creating an archive that lets anyone plumb millions of examples of paid messaging to see who paid for what—a move it hopes will lead researchers to study the way issues-related advertising on the platform gets used and abused. “We can’t figure this stuff out ourselves,” says Leathern, who spearheads this work. “We need third parties.”

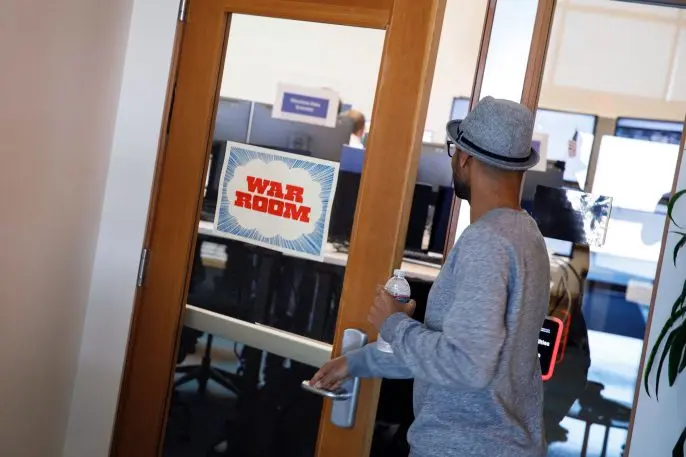

The scale of this response is “a really important marker,” says Nathaniel Gleicher, the former Obama-era U.S. Department of Justice and White House official who joined the company as head of cybersecurity policy early this year. “But there’s another piece that isn’t as obvious, which is that we’ve also brought together teams so that they can collaborate more effectively. I now drive the team that has product policy, the product engineers and our threat intelligence investigators, all working hand in hand on this stuff.” In other words, the cross-pollination effort involves vastly more people than can fit in the new election “war room” that Facebook set up at its Menlo Park, California, headquarters for real-time interdisciplinary decision making.

Mitchell says that some folks will take issue with Facebook’s decisions, even if the company comes up with optimal policies and executes them more or less perfectly. “And then on top of that, we’re also dealing with instances in which we’ve enforced incorrectly,” he adds. “And then on top of that, we’re dealing with instances in which we discovered that the policy line should live in a different place. And on top of that, we’re dealing with issues where maybe we think the reviewer made the right decision with everything they had at their disposal, but maybe the responsibility lies on us to actually give them a different view to get the right outcome.”

That’s a lot of layers of decision making that Facebook must get right. And many of the pieces of political content it must assess prompt tricky questions, not easy calls. Gleicher compares the company’s challenge to looking for a needle in a haystack—if the haystack were made of nothing but needles.

Remove or reduce?

For all the ways Facebook can be abused—and all the ways it can defend itself—the company sees the problems and its solutions in simple terms at their highest level. “There’s bad actors, bad behavior, and bad content,” says Lyons, whose job involves shaping the feed that’s every user’s principal gateway to content—good, bad, or indifferent. “And there are three things that we can do: We can remove, we can reduce distribution, or we can give people more context. Basically, everything that we do is some combination of those various problems and those various actions.”

Rather than being quick to remove content, Facebook has often chosen to merely reduce its distribution. That is, it makes it less likely that its algorithm will give something a place of prominence in users’ news feeds. “There’s a lot of content that we’re probably never going to broaden community standards to cover, because we think that that would not be striking the right balance between being a platform that enables free expression while also protecting an authentic and safe community,” Lyons explains. This includes garden-variety misinformation, which it attempts to nudge downward in feeds—and works with fact checkers to debunk—but still doesn’t ban outright on principle.

Lyons stresses that pushing down pieces of misinformation has benefits beyond the simple fact that it makes them less prominent. Sketchy content is often set loose on the social network by purveyors of clickbaity hoax sites monetized through ad networks. If Facebook members don’t see the stories, they won’t click on them, and that business model starts to fall apart. “By reducing the amount of distribution and therefore changing the incentives and the financial returns, we’re able to limit the impact of that type of content,” she says.

Facebook has often been criticized for this practice of demoting rather than deleting questionable posts, and in October, it took more punishing action by purging 251 accounts and 559 pages for spreading political spam—both right- and left-leaning—on its network. Even here, however, it wasn’t taking a stance on the material itself (sample headline: “Maxine Waters Just Took It to Another LEVEL . . . Is She Demented?”). Instead, the proprietors of the accounts and pages in question were penalized for using “coordinated inauthentic behavior” to drive Facebook users to ad-filled sites.

Of course, the efforts that have originated in Russia and Iran to pelt Facebook members with propaganda were driven by a desire to tamper with politics, not to game ad networks. Other abusers of the platform are also unmotivated by money. And in the U.S. and elsewhere, Facebook is targeting “any coordinated attempts to manipulate or corrupt public debate for a strategic gain,” says Gleicher. “What my team focuses on is understanding the ways that actors are looking to manipulate our platform. How do we identify the particular behaviors that they use over and over again? And how do we make those behaviors incredibly difficult?”

In July, Facebook responded to such material by updating its list of taboos to prohibit “misinformation that has the potential to contribute to imminent violence or physical harm.” Even in the U.S., in the wake of online hate presaging real-world atrocity, the policy change seems suddenly relevant.

Numbers big and small

Like everything else about Facebook, its war on platform abuse involves gigantic numbers. In the first quarter of 2018, for instance, the company removed 583 million fake accounts—many shortly after they were created—and 837 million pieces of spam. Since political manipulation often involves fraudulent accounts stuffing the network with false content, such automated mass deletion is an important part of the company’s measures against election interference.

But the truth is that the battle between Facebook and those who engage in political interference isn’t purely a game of bot versus algorithm. On both sides, much of the heavy lifting is done by human beings doing targeted work.

“We’ve actually been able to do something like 10 or 12 major takedowns over the past eight months,” says Gleicher. “That may sound like a small number, but the truth is, each of those takedowns is hundreds, and in some cases thousands, of investigator hours driven to finding and rooting out these very sophisticated actors that are intentionally trying to find a weak point in our security and the sort of media ecosystem of society. And so each one of those is a beachhead to having a big impact in the short term, but even more importantly understanding these new behaviors and getting ahead of the curve in the longer term.”

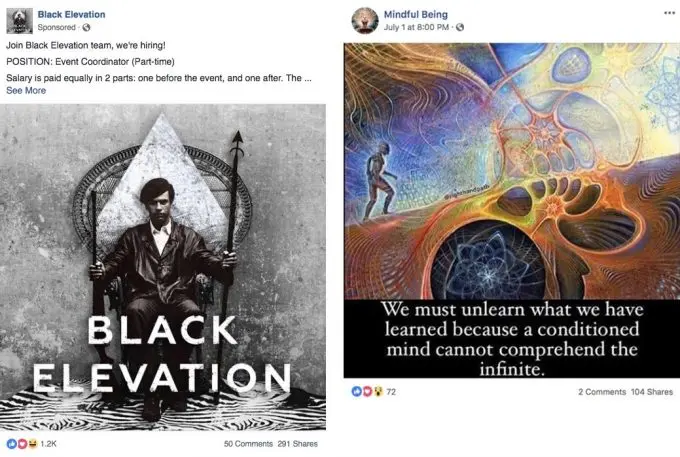

In July, the company removed 32 pages and accounts on the grounds that they were engaged in coordinated inauthentic behavior and had links to Russia’s Internet Research Agency (IRA) troll farm. With names such as “Black Elevation,” “Mindful Being,” and “Resisters,” the pages didn’t show obvious signs of Russian ties, and the IRA’s members have gotten better at covering their tracks, Facebook says. For instance, they avoided posting from Russian IP addresses and promoted their pages with ads purchased through a third party.

“We got some criticism for it,” Gleicher acknowledges. “It’s a really challenging balance to strike. And we expect that we and the other platforms and all of society are going to need to figure out how to strike that balance.”

Striking balance is also core to the work done by Mitchell’s group that specializes in giving extra attention to a relatively small quantity of thorny issues relating to policy enforcement. The team’s existence is an acknowledgment that hiring thousands of people to police content creates problems as well as solving them. In some cases, the initial call will simply be wrong; in others, judging a piece of content will lead Facebook to reassess its policies and procedures in ways that require discussion among high-level employees.

Mitchell provides an example. One political ad submitted by a congressional candidate was flagged by the platform for potentially violating a policy that forbids imagery that’s shocking, scary, gory, violent, or sensational. A human reviewer checked out the ad, concluded that it broke the rule, and rejected it.

Here again, horrific experiences in Myanmar have taught Facebook lessons with broader resonance. In that country, violent content often wasn’t being reported by members, because it tended to be displayed to users who approved of it; that told the company that it needed to be more proactive and less reliant on users telling it about objectionable material. In other instances, imagery that contained hate speech was being mistakenly flagged for nudity, and therefore routed to reviewers who didn’t speak Burmese. “The idea being, you don’t need to speak a particular language to identify a nude image,” explains Mitchell, adding that Facebook now errs on the side of showing such content to reviewers who are fluent in Burmese.

The precise breakdown of content policing between software, frontline content moderators, and investigators such as those on Mitchell’s team may evolve over time, but Facebook says that the big picture will still involve both technology and humans. “We couldn’t do the scale nor have the consistency without bringing them together,” says Leathern. “We’ll figure out what the right mix of those things are. But I feel that for a long time, it’ll still be some combination of both of those things.”

Miles to go

Facebook may be careful not to declare any lasting victories in the war against political misuse of the platform, but is it making real progress? In September, a study concluded that it was, reporting that user interactions with fake news on Facebook fell by 65% between December 2016 and July 2018. Steep though that decline is, it still leaves about 70 million such interactions a month, which helps explain why alarming examples still abound.

So do seeming loopholes in Facebook’s new procedures and policies. In the interest of transparency, the company now requires “Paid by” disclosures on issues-related ads, similar to those on TV political commercials. Last month, however, Vice’s William Turton wrote about an investigation in which his publication fibbed that it was buying ads on behalf of sitting U.S. senators and Facebook okayed the purchases. Vice tested this process 100 times—once for every senator—and got approval every time. (Facebook says it’s looking at further safeguards.)

Overall, Theresa Payton, CEO of security firm Fortalice Solutions and White House CIO during the George W. Bush administration, gives Facebook credit for stepping up its response to the election-related problems it’s identified, though she says it should coordinate more closely with other online services as well as government institutions such as the intelligence agencies and the Department of Homeland Security. The bad guys, she says, “aren’t going to suddenly say, ‘You know what? We lost. Democracy is alive and we’re not going to meddle anymore.’ They’re just going to up their A game.”

Facebook wouldn’t disagree. “In any space that is essentially a security challenge, you’re constantly trying to fight the problems that you know exist, and also prepare for problems that you expect to be emerging, so that you don’t find yourself unprepared,” says Lyons. “Which I would say we’ve acknowledged we were at different points in the last several years.” She points to “deepfake” videos—meldings of existing video and computer graphics which convincingly simulate well-known people doing or saying something they haven’t—as a potentially alluring tool for political interference that the company has its eye on.

The very name “deepfake” conveys that hoax videos wouldn’t be an altogether new kind of hazard for Facebook to contend with—just weaponized fake news in an even more dangerous package. “I don’t think there’s ever going to be a world where there’s no false news,” Lyons says. “And since Facebook reflects what people are talking about, that means there’s also going to be false news that’s shared on Facebook.”

As those who would leverage this fact grow only wilier—and throw ever-more sophisticated technology at their efforts—Facebook too must up its A game. Not just for any particular election, but forever.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.