This story is part of our Startup Resistance series, which profiles the entrepreneurs and activists addressing issues that have been neglected or opposed by the Trump administration.

After the 2012 re-election of Barack Obama, the Democratic party was seen as the leader in using technology to get voters to the polls. The former president’s campaign team was known for its innovations in organizing, fundraising, and get-out-the-vote tools. The Democratic National Committee sat atop a large voter file, populated with data collected by Obama for America volunteers. But somehow, as we all know by now, the DNC data platform and tools languished for a few years and was not used very effectively by the Clinton campaign to get out the vote in 2016.

Meanwhile GOP forces were dumping millions into an effort to retool their ground game. Conservative donors, the Koch brothers, financed a new voter record broker called i360, which augmented the public voter data with lots of original and third-party financial (credit data) and consumer preference (shopping habits) data. The Kochs also incubated new campaign tech startups through their Associate Program. And billionaire hedge fund manager Robert Mercer put money behind a fancy new “psychographics” voter targeting scheme via Cambridge Analytica, which would later become the pariah of the whole campaign data science scene.

The Trump campaign was skeptical of tech approaches to organizing throughout the presidential primaries, but apparently saw the light in time for the general election. The campaign’s data analytics and digital communications operation was small, but effective. It ended up playing a key role in motivating people to go out and vote Trump in crucial electoral college states like Michigan, Ohio, and Florida. It was also effective in sowing plenty of doubt about his opponent and the election process in general, giving potential Hillary voters reasons to stay home.

Now the game is changing again. If the Democrats’ old slogan was “Stronger Together” in 2016, this year it’s “Never Again.” The party is trying to once again push ahead of the Republicans to help deliver the blue wave of voters it needs to take back the House of Representatives and possibly (not probably) the Senate.

And that challenge is compounded by new fears over voter suppression, which tends to disproportionately depress turnout by African-American and Hispanic voters who are more likely to vote for Democrats. Since 2010, at least two dozen states, most of which are controlled by Republicans, have introduced measures that restrict voting access. According to the Brennan Center for Justice, 13 states introduced or tightened restrictive voter ID laws, 11 have laws that make it more difficult for residents to register, seven have sharply cut back early voting, and three have “moved to make it more difficult to return voting rights to people with criminal convictions,” reports Al-Jazeera.

Here are some of the startups that are expected to make a difference on Election Night, November 6.

Bringing the money: Act Blue

It’s useful to look at the landscape of Democratic campaign tech through the lens of Act Blue. Act Blue leverages concepts near and dear to the tech industry–like erasing “friction points” and cultivating “network effects”–to increase the flow of dollars to Democratic campaigns. In this cycle, with control of the Senate and House at stake, the increased flow of money could make races in deep red states competitive and races in swing states likely wins for Democrats.

The small Massachusetts nonprofit has created a boom in small-donation giving to Democratic campaigns and grassroots progressive causes. Campaigns use Act Blue tools to build contribution forms and then host the forms on Act Blue’s secure website. They can then use their own social media or email lists to direct donors to those forms. Act Blue’s major friction-removing asset is that it can store the credit card numbers of donors, so that donors can make repeat donations to a given Democratic campaign, or make a donation to a different Democratic campaign with just a few clicks.

The results of this are measurable and obvious. For example, The Beto O’Rourke Senate bid in Texas raised more money–$38 million–in the July through September reporting period than any other Senate campaign in history, all of it composed of small donations via Act Blue. O’Rourke has roughly $70 million in total, much of it via small donations from outside Texas. An analysis by FiveThirtyEight and the Center for Public Integrity found that Democrats running for congressional seats this year have collectively raised $276 million in small-dollar contributions–that’s more than three times $81 million in small donations raised by Democrats in the 2014 midterms. Act Blue is a big reason for that.

Bringing the people: MobilizeAmerica

If Act Blue refers to itself as a “conduit” for the smooth flow of funds, MobilizeAmerica might refer to itself as a conduit for Democratic volunteerism. MobilizeAmerica is a two-sided marketplace that connects volunteers with campaign events. The startup, which launched in January 2017, was incubated and accelerated by Higher Ground Labs, then was adopted by the Democratic National Committee, which helped it scale up.

The idea behind MobilizeAmerica is to provide campaigns and progressive organizations with a centralized place to recruit volunteers. Campaigns and groups can go to the platform and create events, then supportive organizations can mobilize their members to attend them. Because MobilizeAmerica has created a central database of more than 20,000 events, individual volunteers can use the platform to view numerous Democratic volunteering gigs in their area. If you live in Lincoln, Nebraska you can visit the site and find registration events, fundraising events, and canvasing groups to volunteer for.

“Amid all the anger and desperation in the wake of Trump’s election, lots of progressives wanted to get involved, but the emerging movement lacked the technology to convert this anger into volunteer action,” says MobilizeAmerica cofounder and CEO Alfred Johnson. Johnson is an Obama campaign alum who also worked in the Treasury Department and as a special assistant to the White House chief of staff. He cofounded the company with Allen Kramer, an alum of the Hillary ’16 campaign.

“After the 2016 election, we were seeing this massive mobilization: SwingLeft was emerging, signing up thousands and thousands of people, and existing groups like the ACLU and Planned Parenthood were seeing their recruiting go way up,” Johnson says. “But it wasn’t flowing through to actual volunteering. These groups had neither the tools or the infrastructure to turn all that interest into volunteer action, nor did they have the tools to collaborate with each other.”

MobilizeAmerica provides that infrastructure. The startup has worked with the DNC and numerous state committees to make sure that the Democratic campaigns in all the key midterm races can post events and other volunteer opportunities. Big Democratic groups like SwingLeft and MoveOn.org now host their own branded events pages on MobilizeAmerica so that volunteers have the experience of signing up directly with their group. The groups can then use email or social media to point people to those events on their MobileAmerica page. So can campaigns, and, importantly, the data collected through those pages is instantaneously connected to the back-end information systems used by the campaigns and groups to organize volunteers.

“Everything we’ve done is about how do we get the most people to act, and amplify the impact of this movement,” Johnson told me.

The company’s reach across the Democratic-aligned organizational landscape has grown quickly. Johnson told me MobilizeAmerica is now working with more than 515 campaigns and more than 640 progressive organizations, including the DCCC, OFA, and Crooked Media. Johnson says the platform hosts events across all 50 states and the District of Columbia and has enabled more than 270,000 individuals to sign up for more than 500,000 volunteer shifts (two- to three-hour stints of canvassing or phone banking).

The “texting” election–Hustle and Relay

Campaigns want to meet voters where they live, and for most of us in the 21st century, that means on the smartphone. And because calls to our smartphones are annoying (and getting more so), that leaves text messaging. After Obama used text messages a bit in 2012 (to announce his candidacy and running mate), and after Bernie used it in 2016 (to organize volunteers), the floodgates have opened in the midterms of 2018.

Since it’s legally dicey to send bulk texts out to huge numbers of strangers, campaigns have turned to something called peer-to-peer texting. P2P texting operates within safe legal waters by requiring that a real human press the Send button on each one. Pretty much everything else can be automated: The texting platform generates the appropriate message (depending on the stage of the campaign and the candidates’ goals) and fills in the target phone number. Democratic campaigns have been arming volunteers with P2P texting apps like Hustle and Relay to send texts to likely voters.

Hustle was started by ex-Facebook data scientist Roddy Lindsay (CEO), Obama’s former Nevada new media director Perry Rosenstein, and CTO Tyler Brock. (Rosenstein has since departed.) The company has $41 million in venture capital behind it from high-profile backers like Salesforce and Google Ventures, and is said to be growing quickly. The company works only with Democratic candidates and causes, and currently 46 state Democratic parties. “What it’s allowed us to do is build trust with the Democratic party and progressive organizations,” Lindsay told TechCrunch. “We don’t have to worry about celebrating our clients’ success and offending other clients.”

Hustle was involved in one of the biggest Democratic victories since the disastrous 2016 election–Doug Jones’s impressive victory against Republican Roy Moore in an Alabama special election in December 2017 for the Senate seat left vacant by attorney general Jeff Sessions. Jones set up “texting banks” where volunteers sat and used the Hustle platform to reach out to prospective voters. Jones volunteers and supporters sent a total of 1.4 million texts by election day. The text messages were critical in the final weeks of the election, when they were used to remind people to vote, and guide them to their nearest polling station.

P2P texting played a major role in another major post-2016 progressive win when Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez stunned 10-term incumbent Joseph Crowley to win the the Democratic primary in New York’s 14th congressional district (parts of the Bronx and Queens) back in June. Her campaign used the Relay P2P texting app to get her supporters out to the polls on voting day.

Challenger @Ocasio2018 toppled one of the top Democrats in Congress, @repjoecrowley, Tuesday night in their primary in the 14th District. The victory stunned even her, live on our channel. #NY1Politics https://t.co/fnK1O0bacz pic.twitter.com/RjuqHJpn1p

— Spectrum News NY1 (@NY1) June 27, 2018

Relay was founded by Daniel Souweine (CEO) and Catherine Aronson (CTO), each of whom worked on the texting operating of Bernie Sanders’ 2016 run for the presidency. Since launching in August of 2016, Relay says that it has sent more than 60 million text messages on behalf of 300 campaigns and organizations. P2P platforms usually charge between 10 and 30 cents per text, with volume discounts.

Campaign officials say voters are more likely to turn out to vote on Election Day if they receive a reminder text. The danger, of course, is sending too many texts to potential voters, or sending the texts to people who don’t want to receive them. Both of these things are already happening, but so far the positive results seem to outweigh the negative. We’ll know for sure on November 6th.

Relational organizing: VoteWithMe, Outvote, VoterCircle, Team

Political campaigns have long tried to get volunteers to reach out to their own personal networks of friends and family members to find and enlist new supporters. It’s a concept known as “relational organizing,” and it typically results in far higher response rates than phone banking and canvassing, which normally entails a stranger cold-calling on a stranger. Relational organizing has proved especially effective with younger voters and those in minority communities. What’s new this election cycle is that relational organizing has gone digital.

As you might expect, the technology comes in various shapes and colors. Outvote and VoteWithMe both ask the volunteer users for permission to access the contact list in their mobile phone to find Democratic voters in key districts who might be persuaded to register (if they’re not already) and vote. They do this by cross-referencing the contact names with the voter record, which they either get from the party or from a broker like NGP-VAN.

VoteWithMe was created by Mikey Dickerson and his new company, the New Data Project. Dickerson is an ex-Googler who came to fame by fixing the Obamacare Healthcare.gov site, and stayed in D.C. to become the first head of the United States Digital Service. Dickerson and company beta-tested the VoteWithMe app in Democrat Conor Lamb’s surprising victory last March in the special election for the House seat representing Pennsylvania’s 18th district. Dickerson raised “between one and two million” dollars to build VoteWithMe, some of it from former Google CEO Eric Schmidt and former U.S. CTO Todd Park.

While VoteWithMe is a consumer app, campaigns can pay for a white-label version of the OutVote platform and app.”What we do is meant to plug into the tech tool stack of existing political campaigns,” OutVote cofounder Naseem Makiya told me. “It’s a branded app experience for their organizations.” Outvote, which was a Y-Combinator company, is currently being used by a couple of Senate campaigns, Makiya said, as well as in a number of House races.

Outvote has also partnered with other Democratic grassroots organizations like MoveOn.org, Swing Left, and Flippable. Those groups are urging members to use Outvote to contact persuadable friends who live in districts where the group has endorsed a candidate, and get them out to vote.

Another company, VoterCircle, uses a very similar approach. Users sync their contacts against a voter file to find potential Democratic voters for a specific candidate or cause. Then VoterCircle suggests email text that can be sent to the target contacts, including for subsequent emails that provide updates as Election Day approaches. VoterCircle was used in the campaigns of a number of Democrats who won seats in the Virginia House of Delegates seats last year. It was also used in Doug Jones’s defeat of Republican Roy Moore in Alabama’s special election last year.

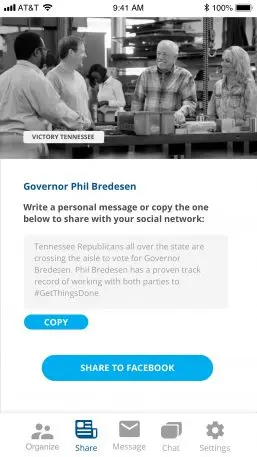

Tuesday Company’s Team app has seen considerable pickup among Democratic campaigns this cycle because of its broad approach to relational organizing. Like OutVote and VoteWithMe, Team identifies key people in the user’s personal networks and lets them connect with them via text, email, phone, or Facebook Messenger. But Team’s central goal seems to be enlisting volunteers and supporters to share pieces of content and messaging (like new campaign videos) out to their Facebook networks.

The Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee (DCCC) announced that Democratic campaigns in each of its targeted House races is using Teams for social engagement. The DCCC and Tuesday Company are aiming to use the app as a tool to turn out young people, people of color, and low-income voters–all groups who don’t typically show up for midterm elections.Tuesday Company says it expects that when the midterms are over more than a million voters will have been contacted via Team by thousands of volunteers.

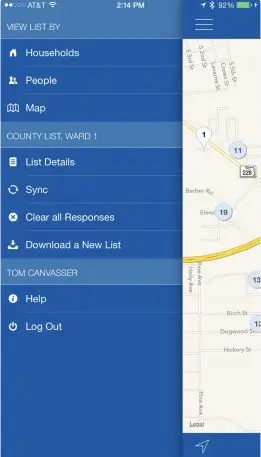

Managing the list: NGP Van MiniVAN

NGP VAN is hardly a new name in political circles. It’s the technology company that’s been managing and licensing the official Democratic voter file since 2004. Managing such a list is a messy job requiring a lot of rationalizing of differing formats, and the cleanup of incorrect or unnecessary data. Voter list brokers often add value to the list by including phone numbers, as well.

Almost all Democratic campaigns use the NGP VAN voter file, and a good number use the NGP VAN desktop application to manage their outreach, organization, and canvassing effort. It all integrates with a number of apps on the front end, chiefly the MiniVAN mobile canvassing app. Managing the names, addresses, questionnaires, and answers of door-to-door canvassing was, not too long ago, all done on paper. This led to errors, missed data, and wasted time. But conversion to digital and mobile has started to pay big dividends.

The MiniVAN app can access the voter file and surface a questionnaire that’s appropriate for the respondent behind each door, for instance. The app has added a new GPS feature that helps the canvasser walk the shortest route between the homes that need to be canvassed in the shortest time.

Now that the campaigns are entering its crucial last few weeks, the MiniVan app is even more crucial to Democratic campaigns.

This pushes usage of the app way up, Tharp says, because everyone involved in the campaign is called upon to go and make sure people who’ve pledged their support actually go out and cast their vote. “It’s pretty much all hands on deck,” he says.

Last weekend–October 20th and 21st–72,757 people were out canvassing for Democratic candidates and causes, Tharp told me. That’s up 19.3% from the previous weekend, and up 241% from the weekend of October 22nd and 23rd just before the general election of 2016, Tharp said.

Blue incubator: Higher Ground Labs

One of the reasons the Democrats may have fallen behind the GOP is that they’ve relied on big presidential campaigns to act as the innovation engines that create new election-changing technologies. And both Obama campaigns are credited with pushing that cause forward in meaningful ways, especially in voter modeling and targeting, and GOTV. But the founders of Higher Ground Labs make the point that the pol tech race can’t be a once-every-four-years thing. For Democrats to win, the innovation has to be happening constantly.

And right now, surviving as a full-time campaign tech startup isn’t easy. “Political startups have to walk a lonely path, starting with how do you get funding, how do you meet people, how to find mentors to guide you,” HGL cofounder Shomik Dutta told me. It’s not easy luring investment money when your business is tied to the timing of elections; the long years in between races can be hard times. Meanwhile, on the GOP side, wealthy players like the Kochs and Mercers have been willing to shell out enough cash to keep companies like Cambridge Analytica and i365 alive between cycles.

Higher Ground Labs is taking an approach to incubating new progressive campaign tech startups that feels more like Silicon Valley. HGL incubates, accelerates, and invests seed capital in startups whose technology addresses a key pain point or challenge faced by modern political campaigns, cofounder Betsy Hoover told me. For instance, political polling is so expensive and difficult that smaller campaigns sometimes do very little of it, and larger ones sometimes hang on to polling results after they’ve gone stale. HGL invested in a small data science company called Change Research that offers new, and less expensive, approaches to reaching respondents via the web. Understanding the real meaning of voter survey responses is another challenge: HGL invested in Avalanche Labs, which has an algorithm that finds the hidden meanings in the words chosen by respondents.

HGL raised its fund from a number of high-profile Silicon Valley figures, including LinkedIn founder Reid Hoffman, Lowercase Capital founder Chris Sacca, and famed angel investor Ron Conway. So far, HGL has invested a total of $5.5 million in 23 startups in two rounds, one in August 2017 and one in April 2018. The fund takes between 6% and 8% equity in its portfolio companies. Some of HGL’s portfolio companies are longer-term bets. It invested in Factbase, whose technology helps campaigns track everything its opposition says publicly or online, looking for position shifts, distortions of truth, or a speaker’s unease talking about an issue, policy, or position.

But a good number of the HGL’s first cohort in 2017 are already making a difference. Eight of them were involved in the Virginia House of Delegates elections last November (Virginia’s state-level elections are held in off-years, providing a convenient test case for new pol-tech apps and services).

Hoover, Dutta, and HGL’s other founder, Andrew McLaughlin, all go way back in tech and Democratic politics. Hoover worked as a digital organizer in Obama ’08 and as National Digital Organizing Director in Obama ’12. Dutta worked in both Obama campaigns and served as special assistant to the White House counsel under Obama. McLaughlin was VP of global public policy at Google, later became CEO of Digg and then Instapaper, and eventually went to work as Deputy CTO of the U.S. under Obama.

HGL’s Advisory Board is a bit of a who’s who of Democratic operatives. Twenty-one of the 40 people listed (including Pod Save America’s Jon Favreau) held senior positions in at least one Obama presidential campaigns, or served in the Obama Administration. Five more worked for the Hillary campaign in 2016.

Hoover told me HGL works with the DNC often, and in a number of different ways, specifically with the party’s digital and political mobilization teams. “They’ve encouraged us to focus on certain technologies, and helped inform our investment thesis,” she said.

“We really see our role as an external incubator that can take the time to test-drive new technologies outside the party,” Hoover said. “The party’s role, then, is to take the successful ones and help scale them up,” she said.

The DNC hired former Twitter and Uber executive Raffi Krikorian to help solidify the way the party works with the private sector to test and concertize new progressive pol-tech. It becomes clear when talking to Krikorian that the DNC can’t be an incubator for new technologies; it has to focus on delivering the votes needed to win the election happening right now.

“It’s a good thing that we have these private companies out there to take the risk,” Krikorian told me. “I imagine that if we had an unlimited budget we would be doubling down on the things that we already know work, we’d be using it to polish them up and make them better. But there’s an opportunity in the private sector to take on bigger risks that the DNC can’t. We need people in the private sector to try 10 things to find the one thing that works.”

BallotReady

One of the reasons people don’t get themselves to the polls is because they don’t fully understand the issues and people they’re being asked to vote on. Or, often, they vote for the high-profile names at the top of the ballot, leaving blank the Democratic candidates and causes farther down. When they understand the issues, they not only show up to vote, they’re more likely to attend campaign events and even volunteer for causes they believe in.

BallotReady does the groundwork of going to every state and local jurisdiction to collect all the ballots for every election in a cycle. In some places there is no digital version of the ballot so it has to be data-entered in BallotReady’s systems. In the end, the organization compiles voter guides for every race or referendum down to the local level in all 50 states. It provides the names of every candidate along with a sampling of statements the candidate has made about his or her position on various issues. Voters can bring their custom voter guide into the voting booth on their phone if their state permits it or, if not, they can print it out and bring it in with them.

A study conducted in a 2017 Virginia election found that texting voters a link to the BallotReady voter guide was more likely to get someone to vote than applying social pressure or sending them text messages about polling place locations. BallotReady proves the “educate to motivate” maxim to be true in politics.

Voters can go directly to BallotReady to get their ballot (you just fill in your local address). Or an advocacy organization like Planned Parenthood or Emily’s List might send out a branded version of the BallotReady ballot to its members or mailing list names. BallotReady tested its ballot during the primaries in Illinois in March, and the ballot will be in wide use by voters everywhere during the midterms.

Flippable

National politics tends to draw most of our attention and donation dollars. Flippable, however, is focused on helping Democrats win state house races. And for good reason. Much of the power to draw district lines and set voting rules rests with the state legislatures. And the party that controls the state legislature has the power to change those rules to give its members–both at the state and national level–the best chance of winning or retaining power.

In many states, the person who wins a seat in the legislature can vote to change the borders of his own district to disadvantage a potential challenger. And in our hyper-partisan environment, the party that holds the seats makes the rules, period, making it a dangerous and self-perpetuating problem.

That’s one of the reasons that Flippable has chosen to focus on fundraising for Democratic candidates for state legislatures. “You can spend every two years trying to win back 16-22 unearned seats in Congress that Republicans have gotten through gerrymandering, spending millions of dollars on each race; you can try to take the drawing of district lines out the hands of lawmakers,” Flippable cofounder Catherine Vaughan says.

“Or you can spend the really smart money on state legislatures, because they are the ones that draw election lines, they are the ones who decide on early voting, and automatic voter registration,” Vaughan says. “All of these decisions come down to the state level.”

Vaughan and her cofounder Chris Walsh were a couple of Clinton campaign volunteers working in Ohio when Trump won the presidency. Soon after, they met for a drink and devised a plan for an organization that would help the rebuilding effort by focusing on winning Democratic seats in state houses across the country.

Flippable looks at the whole landscape of state legislatures, then makes strategic choices on where to best apply its members’ donation money. It might focus money on winning legislature seats in states that are likely to try to change voting district lines or voting rules. It might put money behind Democratic candidates in states that are likely to make major policy decisions on issues like gun control or abortion rights. Or, it might give more money to the campaigns of Democratic candidates in legislatures where the party has a reasonably good chance of taking majority control.

A Big Bang

Everybody remembers where they were when Trump won the presidency in 2016. For many of the progressives in this story, there was a period of moving through the seven stages of grief (especially the anger stage), but soon a solemn mood of creativity and problem-solving set in.

“When this huge disaster happened in 2016, we didn’t just react out of blind rage; we began asking, ‘What is the smartest way to intervene to fix our un-democratic system?'” Flippable’s Catherine Vaughn told me.

“I think there are some in the progressive movement who are alarmist, but rage will only get you so far–we need to cultivate a group of voters, volunteers, and donors who are not alarmist, but who have this persistent resolve to get the job done.”

Flippable was born in the weeks after the election, as were many other progressive pol-tech companies. Trump’s victory was, in a way, a Big Bang that blasted into existence a new ecosystem of left-leaning startup companies, platforms, and apps all designed to return progressives and Democrats to power at all levels of government.

Crucially, these companies aren’t working in their own silos. Many of them were started by (or staffed by) alumni of one of the Obama campaigns, which were the very incubators for new pol-tech innovation in their own right. There is an awareness of the wider ecosystem and a desire to provide ways of making different parts of the system work together. You can see that in the integration of the Mobilize America technology into the technology stacks used by the campaigns, usually NGP VAN. Where these players once acted in silos, forming one-to-one relationships with individual campaigns, they now act as platforms that allow for freer data flow and network effects.

All the new tech tools are, in some way, just infrastructure, just supporting technology to the persuasive political messages that persuade and motivate. No amount of it is any good without the focused platform and effective people that went lacking in 2016. And it’s all opposed by a strong adversary, the GOP, whose main product has become dumbed-down, nationalist identity politics, and its main tactics identity politics, voter suppression, incivility, and attacks on the media. But they are shrewd, focused on long-term goals, and increasingly savvy at using data science and social media to excite their base and get them to the polls. It’s a hard fight. Progressives must get used to a never-ending arms race in campaign tech of all kinds. In a world where big numbers of people still don’t vote, it’s crucial that Democrats maintain a full-time system of funding, creating, and honing new political tech–one that makes a habit of incorporating the best ideas of Silicon Valley.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.