Prisons aren’t usually thought of as high-tech environments, but increasingly, when U.S. inmates connect with the outside world, they’re doing so through a digital screen. Vendors are offering tablets, e-readers, and even video-conferencing technology to replace books, physical mail, and even in-person visits at prisons throughout the country. The companies cite convenience and a need to curb the smuggling of contraband, but critics raise concerns that such technologies further distance inmates from real human contact and could inhibit their rehabilitation.

Securus, a Dallas-based company that’s one of the largest providers of inmate telecom services, has distributed close to 170,000 digital tablets to U.S. inmates, who use them to listen to music, use educational materials, and communicate with loved ones in the outside world. Reston, Virginia-based GTL, Securus’s biggest rival, reports that it has provided some 350,000 inmates across the country with its own locked-down Android tablets with similar features.

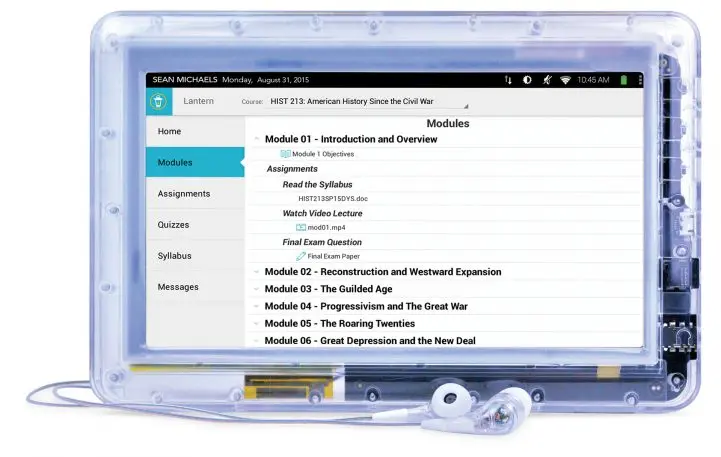

The companies say the devices can help inmates pursue an education behind bars. More than 80,000 incarcerated people have enrolled in free courses through Securus unit JPay’s Lantern learning management software since the platform launched in 2015, earning a total of about 33,000 college credits—and simply stay busy while in prison or jail.

Inmates don’t have direct access to the internet. They can’t stream music on Spotify, enroll in a Coursera class, or download a book from the Kindle Store. Instead, depending on prison rules and technology, they connect wirelessly to central terminals or dock their tablets at specialized kiosks. Then they can do things like download music, movies, and e-books, upload messages to friends and family, and submit coursework for grading, all using apps provided by their institution’s chosen tech vendor.

In many institutions, inmates and their outside contacts can even schedule video chats, connecting through Securus or GTL tech to their loved ones, who use specialized apps on their own computers or phones. Whether they or their friends and family pay for tablets, and how much they pay for media and communications, varies widely from facility to facility.

“It varies dramatically from contract to contract—it really does,” Smith says. “Some agencies provide the tablets at no charge to their inmates, other agencies have inmates purchase a tablet, other agencies allow inmates to rent a tablet for a period of time.”

Video chats ranging from $5 to $13

A Securus website marketing inmate tablet rental programs to outside friends and family shows monthly rental prices ranging from $14.99 to $35. Video rates similarly vary: a 20-minute session costs $5 if you’re contacting inmates of the Franklin County Jail in Massachusetts, $10 to reach the Cochise County Jail in Arizona, and $12.99 for those with loved ones in custody at the Hinds County Detention Services in Mississippi, according to Securus price charts. Inmates and their contacts generally also pay for text and photo messages.

Critics have argued for years that inmate telecom services are overpriced—traditionally, incarcerated people were often limited to prepaid or collect phone calls that cost recipients significantly more than ordinary telephone rates. Today’s video calls and text messages are similarly expensive to anyone used to services like Skype or Google Hangouts.

Smith argues that the pricing compares favorably to what was previously available to inmates. That is, an electronic text or photo message can be cheaper than the cost of a postage stamp. And, he argues, when the full price of an in-person visit is taken into account, including transportation and potential costs like missed work and paid childcare, a video call can be comparatively a good deal.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=1&v=y0XQhr8CYhk

“In-person visitation is not free,” he says, once those indirect costs are included, even if prisons don’t charge for it.

Installing technology in prisons also isn’t free and can be technically complex. That’s especially true as tech firms look to equip aging facilities built of metal and concrete with modern Wi-Fi technology, says Brian Peters, vice president of facility product management at GTL.

“We’ve even come across situations where locations almost act as a Faraday cage,” he says, referring to metal shields that block radio waves. GTL also works with prison authorities to find ways for inmates to charge their tablets, whether that’s using includes electrical outlets in cells, setting up lockers where they can securely plug in the devices, or collecting them overnight to recharge at a central place.

The firms sometimes build out connectivity and offer tablets, video-calling terminals, and other equipment free of charge to the prison, planning to recoup their costs and make money from the costs of calls, digital media, and other offerings.

“Typically the hardware and the infrastructure is free for the correctional facility and inmates, and then GTL will offer the different services on the devices,” Peters says.

Replacing in-person visits with video sessions

In some cases, inmates and their loved ones don’t get to choose between traditional access to visits, media, and mail or their digital equivalents. That’s because some prisons and jails have eliminated in-person visitation, even non-contact visits through a glass partition, controversially moving exclusively to video sessions. Some institutions even use video conferencing with visitors who physically come to prison facilities.

“The video calls are just not a substitute in any way for a real face-to-face visit,” argues David Fathi, director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s National Prison Project, citing court precedents from child custody cases saying video chats aren’t a substitute for in-person visits with parents. “There’s no reason it should be any different in the prison context.”

Some have also ceased to deliver postal mail to inmates, offering only scans or photocopies of letters and cards. And some have phased out longstanding policies that allowed prisoners to receive books from publishers, bookstores, and nonprofit groups, limiting inmates to e-books and whatever might be found in prison libraries.

Critics often argue that prison officials have a budgetary interest in limiting free programs in favor of ones that charge inmates or their loved ones money. That’s because the institutions often get a financial cut of phone rates, video calling fees, and other charges paid to telecom providers. Officials at both GTL and Securus emphasize that the firms don’t themselves set access policies or push prisons to cut traditional forms of contact or literature.

“Securus doesn’t say an agency can no longer accept books or have to shut down their internal library,” Smith says. “That’s really individual agency decisions. We look at providing additional services, not necessarily replacement services.”

Officials in some institutions argue that the more restrictive policies are needed to keep drugs and other banned items from being smuggled into prisons through visitors and mail. Pennsylvania’s Department of Corrections (DOC) imposed a 12-day lockdown in August and September after reports that staff at multiple facilities were sickened by exposure to synthetic drugs allegedly smuggled in through paper mail. After the lockdown lifted, the department instituted new policies where attorney correspondence would be photocopied in front of inmates, with inmates given only the copies; other correspondence would be digitally copied at a Florida facility; and mailed-in paperback books would be eliminated in favor of digital books and what the department has said will be an expanded library system.

“The size of the collections varies, but we are talking about at least 10,000-15,000 books, and dozens of periodicals and newspapers,” writes Amy Worden, press secretary for the Department of Corrections, in an email. “If a library doesn’t have a particular book, librarians will work to get that book into the collection.”

$147 for e-books with a limited selection of classics

The policy has drawn criticism from groups like Philadelphia’s Amistad Law Project, which specializes in prison advocacy, and Books Through Bars, a Philadelphia nonprofit that provides books to people in prison in Pennsylvania and nearby states. Inmates or their loved ones need to spend $147 for GTL tablets needed to access e-books in the state’s institutions—more than 16,000 out of 47,000 inmates have the devices, Worden says. Only about 8,500 titles are available, many of them books old enough to be in the public domain, says Keir Neuringer, a volunteer with Books Through Bars. The program’s catalog includes numerous works by Victorian writer Anthony Trollope but not commonly requested titles with more relevance to many inmates, like The Autobiography of Malcolm X or Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow, he says.

“The books that are offered are not books that people are looking for in general,” Neuringer says. “What we will do now is we’ll fight to maintain the possibility that individuals can receive books for free from approved vendors such as Books Through Bars.”

Worden says the DOC has launched a program where inmates can request to buy a particular book, and prison authorities will search for it online and inform them of the price. But allowing even approved vendors to send books directly to inmates was too risky, she says.

“Books coming in from outside sources, whether by large vendors like Amazon/Barnes and Noble or donated books were a serious problem,” she writes.”There was no way the DOC could effectively police those packages and it’s easier to smuggle drugs in old books with thick bindings, strange odors, and discolored pages.”

Why is the DOC changing its procedures on mail and book delivery? Because both are primary avenues for drugs to enter prisons. Here are just two examples within the last nine months: first, a Bible shipped from a major book seller containing multiple strips of the drug suboxone pic.twitter.com/fh9rPIrzO4

— PA Department of Corrections (@CorrectionsPA) September 14, 2018

Kris Henderson, legal director at the Amistad Law Project, says something is also lost in the transition to digital mail.

“Just like even really small things, like someone’s mom being able to write them a letter and being able to hold that letter in your hand is no longer possible,” she says.

Generally, for corrections officials, switching to digital communications not only cuts down on the opportunity for contraband smuggling but also enables greater surveillance of inmate activities for suspicious behavior. Video calls, scanned mail, and digital messages can easily be monitored and logged, and tech vendors offer tools to track who inmates are corresponding with and detect sudden shifts, like an inmate suddenly contacting a larger number of outside people or multiple inmates suddenly contacting the same person.

“We provide kind of a big data analytics [tool], which is called THREADS,” says Smith. “It identifies odd communication patterns and notifies corrections staff when it identifies those type of things.”

Different agencies have taken different approaches to balancing security and inmate interests: In Polk County, Florida, where the jail system receives service from Securus, Sheriff Grady Judd replaced mail delivery with digital scans after inmates allegedly became ill from consuming K2 from mailed-in papers that had been doused in the synthetic drug.

https://vimeo.com/282137309

“If you mail traditional mail in, it goes to a third party that scans it in so that they have it on the kiosk in all of the dorms in the jail,” he says. “We save it for them, so when they get out of jail, if they want their paper mail, they can have it.”

The county’s two jails also offer video visits, and Judd says onsite visits are always free to visitors, though neither location offers physical contact in an effort to keep out drugs, with one allowing only video contact even on premises and the other allowing traditional through-the-class contact.

“I underscore this—we’re going to make sure that everybody has the opportunity to visit for free,” Judd says, adding that the county recently increased allowed visitation time.

Some prison systems have also backed away from restrictions: Officials in both Maryland and New York rescinded policies this year that limited access to mailed-in books after protests from literature charities and advocacy groups. And while courts have generally allowed limitations like no-contact visits and restrictions on pornographic or hardcover books, advocates say tighter limits could be found unconstitutional.

“Prisoners retain the right to read”

“The Supreme Court has been very clear—prisoners retain First Amendment rights,” says Fathi. “Prisoners retain the right to read.”

Many prisoner advocates say they’re not at all opposed to introducing technology in prison, as long as institutions don’t simultaneously remove other ways for inmates to access the outside world. And prison tech vendors point out that digital tools can have the same advantages in prison that they do elsewhere, like letting inmates access books, music, and movies on demand without having to wait for their day in the library or hear back from an outside book charity.

“You’ve got those that are incarcerated, sitting idle, without a book in their hands they want to be reading,” says Smith. “E-books really allow that individual to browse the catalog when they want a book, download the book immediately, and begin reading it.”

Educational materials, too, including electronic ways to correspond with instructors, can be just a few taps away, says Ronnie Hopkins, an Akron area man who has written and spoken about his experiences studying with a JPay tablet while incarcerated in Ohio institutions.

“It was super-simple to use it,” says Hopkins, who was released last year after serving time for manufacturing methamphetamine. “It was very convenient.”

One thing technology is unlikely to do is entirely remove drug smuggling from prisons and jails. Critics of recent restrictions regularly point out that there have been plenty of instances of drugs smuggled by corrupt guards, and even as Judd says contact and mail restrictions have eased the jail’s drug problem, he acknowledges it’s unlikely inmates and their associates won’t seek to find ways to continue to sneak in drugs.

“They’ll start trying to fly over with drones or some such business,” he says.

When that day comes, the county’s tech vendor will likely be prepared: Securus announced earlier this year it’s working with Holmdel, New Jersey, drone defense company AeroDefense to deploy its AirWarden drone and pilot location system around the correctional facilities it serves.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.