CRISPR-Cas9–the scissors-like gene-editing technology that could be used to treat cancer, cure genetic diseases like sickle cell anemia, and engineer malaria-resistant mosquitoes or disease-resistant livestock–is cheap and easy enough to use that it has become widespread in labs. But a startup called Synthego, founded by former SpaceX engineers, is trying to make it even more accessible: Click a button on its website, and a cell modified with CRISPR will show up on your doorstep, as long as you’re an academic or working at an institution with credentials.

“You don’t even have to worry about learning CRISPR or anything, it just works,” says Paul Dabrowski, co-founder and CEO of Synthego. “So the idea here is you’re up-leveling the researcher to really be able to focus on the results, and the experiment at hand, rather than the methods or the optimization associated with CRISPR.”

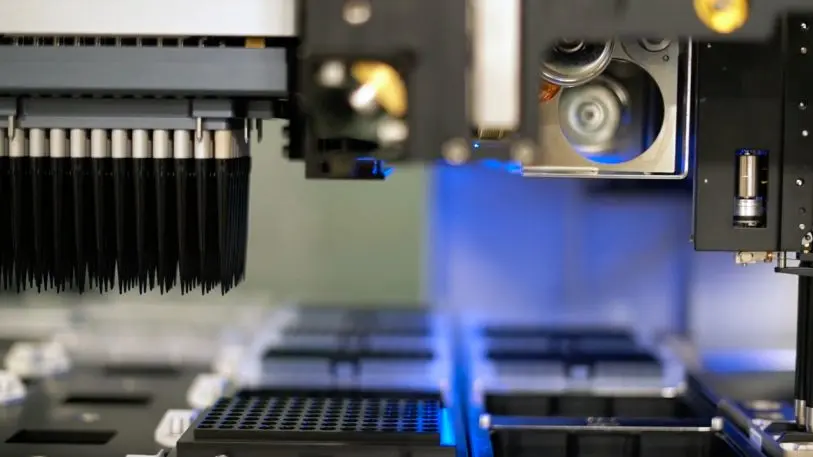

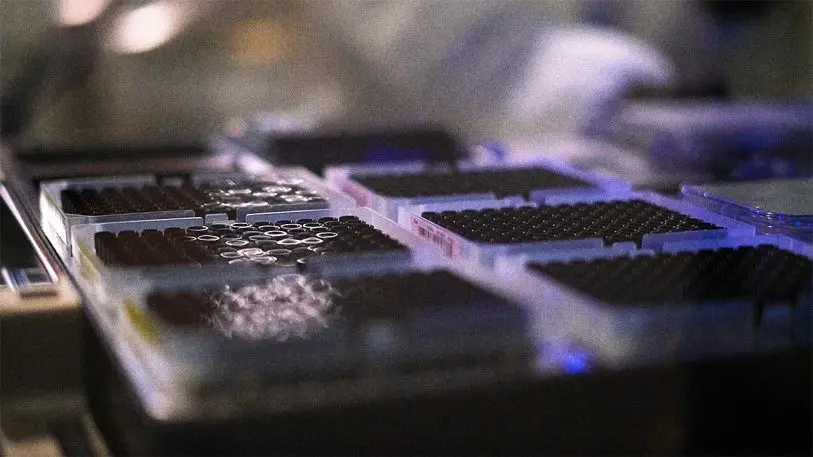

For researchers who want to do their own gene editing, the company also makes kits to simplify that. A researcher chooses the gene they want to knock out, and the startup uses its own software and automated factory to make one step in the process–the synthetic guide RNAs that direct a protein to the right place in DNA to make a cut. For those who don’t want to edit cells, Synthego’s scientists use the same guide RNAs to quickly perform edits themselves. The company works on human cells, rather than plant or animal cells, for researchers who want to develop cures and treatments for disease, and in the future, potentially develop ways to prevent disease.

“A lot of people don’t have the manpower in their lab to do this,” says Leif Oxburgh, a researcher at the Maine Medical Center Research Institute who has tested the new products in his lab, which studies kidney disease. “And so they either don’t do it or they outsource it. If outsourcing comes at a reasonable price and with a guarantee and with this type of time frame that Synthego offers, then it’s a very attractive proposition for a lot of smaller labs who really need the reagent, need that cell, but don’t have the hands and attention to put into that.”

Making the technology more accessible accelerates the need to answer questions about CRISPR that already exist. Because research is in early stages, it’s possible that we still haven’t uncovered unintended impacts that CRISPR may have, and may not fully understand how our bodies will react to treatments; some people may be immune to CRISPR, for example.

“With any early technology, there is a learning phase, and CRISPR is no exception to this,” says Dabrowski. “But what makes CRISPR unique is the vast opportunity it represents, one that can lead us to find cures, treatments, and therapies that are accessible to the masses. This potential, while large, should also be met with the right amount of caution that balances learning at a rapid pace with limiting mistakes. It’s important we press on at a rapid pace to ensure we reach the full potential of the technology via the benefits it represents to society, including preventative cures, elimination of diseases and therapies.”

Jennifer Doudna, a CRISPR pioneer who sits on Synthego’s board, told Fast Company in 2017 that “the worst thing that could happen” would be for CRISPR to speed ahead in labs while people are unaware of the coming impact. But Doudna now says that she believes public understanding has caught up through a deluge of media coverage. “This increased fascination has led to a greater thirst to realize the benefits of CRISPR’s applications,” she says. “In fact, I now receive many more emails every day from members of the public asking about a particular application that could potentially help them or a loved one. Given this context, it is right for the research community to continue forward so we can ultimately use CRISPR to help those in need.”

Still, despite increased coverage, it isn’t clear that most people necessarily understand how the technology works or the impact that it could have. Regulators are also cautious. While early lab experiments with CRISPR aren’t regulated, as a treatment moves along the path to market, it has to get FDA approval for human trials. One major trial planned for a potential treatment for sickle cell disease was recently paused because the FDA needed more information before it could move forward.

Some of the public debate around CRISPR has centered on applications beyond medical treatment–like the fact that the technology could theoretically be used by rich parents who want to select certain traits for their children, such as blue eyes. But while the debate about designer babies continues, Synthego CEO Dabrowski argues that another ethical debate is overlooked–whether new CRISPR-enabled treatments for disease will be accessible to everyone. “This is an important topic and I think kind of the big ethical question of our time: Do things like clinical gene therapies become like vaccines, or do they become million-dollar drugs that very few people can access?” he says.

The company’s work to help researchers use the tool could help lead more quickly to new diagnostics and treatments, or cures, for intractable diseases. While some of the most common genetic diseases, such as sickle cell anemia, are the focus of CRISPR research now, making the technology ubiquitous could mean cures for very rare diseases as well.

“At some point, you could imagine that in the future it becomes cheap enough to develop a new gene therapy that you can really start targeting most, if not all, genetic disorders,” he says. “And maybe the treatments are a couple of hundred dollars, or a couple thousand dollars. We’re literally talking about the opportunity to have vaccines for inherited diseases. That seems like a big deal.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.