In Cape Town, South Africa, where reservoirs dwindled after three years of drought, residents have spent months taking 90-second showers and stockpiling gallons of water. The city closed swimming pools, banned washing cars, and limited water to 13 gallons a person a day (in the U.S., the average person might use around 100 gallons a day). Water use in Cape Town is now half of what it was in 2015, and the city managed to avoid an April 12 prediction of “Day Zero”–the point at which taps run completely dry. But that point may still come later this year, if it still doesn’t rain enough.

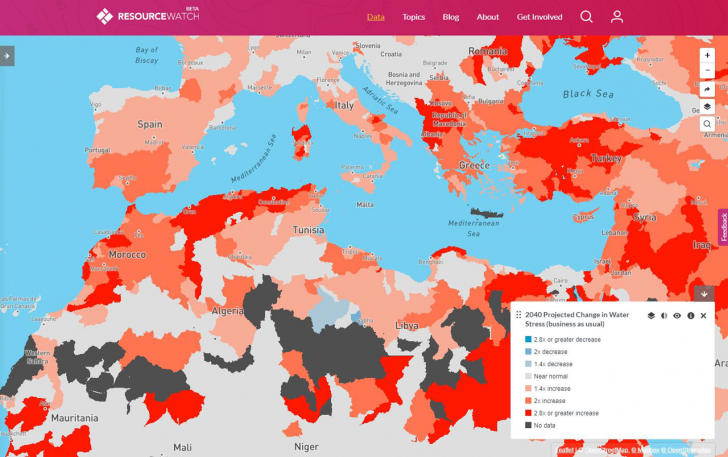

If it eventually hits Day Zero, Cape Town would be the first city to run out of water. But it’s far from the only place struggling with shrinking water supplies. A new report from World Resources Institute looks at four other locations with similar problems, using a new platform called Resource Watch to map out the political, social, and environmental dynamics of each area.

In Morocco, after recurring droughts, the reservoir contained by the Al Massira Dam–which supplies Casablanca and nearby farms with water, and will soon supply Marrakesh–shrank by more than 60% in surface area over the last three years. As the country’s population grows (it’s predicted to potentially double) in large cities over the next few decades, demand for water will increase, while climate change makes drought more likely.

Over the last five years, the Buendia Dam’s reservoir in Spain also shrank more than 60% in surface area because of extreme drought. When some hydropower plants no longer had enough water to operate, electricity prices rose. Farmers have struggled, though agriculture is less critical in Spain than Morocco, where around a third of the population works on farms.

In Iraq, Mosul Dam’s reservoir shrank 60% since the 1990s. New dams and hydropower plants in Turkey have reduced the flow of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers by 80%, cutting off Iraq’s main supply of water for irrigation, drinking water, and power generation. As in other locations, the challenge will get worse as populations grow and climate change continues.

In India, as water shrank behind one key dam, the government decided not to send an allocated amount of water to another dam downstream. That dam, the Sardor Saravor, is the source of drinking water for 30 million people and irrigates more than a million farms. It also provides power, but the water levels have dropped too low for power generation to work. In March, the local government stopped supplying water for irrigation. Ongoing droughts–and debt from failing farms–have been linked to nearly 60,000 farmer suicides in India.

Water stress can also lead to greater instability. “If people run out of water, then they have to move,” says Charles Iceland, the director of global and national water initiatives at World Resources Institute and one of the authors of the report. Syria went through its worst drought in recorded history in the years prior to the current war, and more than a million farmers moved from the countryside from cities. This followed another massive influx of refugees from Iraq to Syrian cities. “Our contention is that the civil war was made more likely and more intense by the drought that happened . . . The repercussions are huge, and potentially even larger in a place like Iraq or Iran.”

There are several steps that cities and countries can take to deal with dwindling water supplies, Iceland says. Most water is used for irrigating crops, so one step may be growing more food in areas that get more rain. Indoor farms can help with some crops–one growing greens recently opened in Dubai–because indoor growing systems use far less water than growing in fields. Reducing food waste can also help. Since around a third of food is never eaten, the water used to grow it is also wasted. In cities, along with campaigns to reduce use, wastewater can be recycled; in Singapore, for example, sewage water is purified and reused in industry. On the coast, as a last resort, some cities may turn to desalination of ocean water.

Iceland also says that because water shortages often aren’t detected quickly enough now, the world needs a real-time monitoring tool for reservoirs, “so that we can move from ad hoc analyses to a systematic, ongoing analysis of the exposure of global populations to shrinking reservoir levels, and the social, economic, and political risks that accompany them.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.