On a road in fourth-century Armenia, the story goes, a Roman centurion met a talking crow. The officer had resolved to convert to Christianity, but now this eloquent crow had come to urge him not to do anything rash. The crow had an idea for the centurion: Delay the conversion; don’t rush. Maybe take a day to think about it.

The centurion, though, would not be put off. He insisted on starting his new life as a believer immediately.

Realizing that the crow was, in fact, the Devil in avian form arrived to tempt him, the centurion–who would later be venerated as St. Expedite, patron saint of procrastinators–did something remarkable: He stomped the talking bird to death.

“You Who Never Delays, I Come To You In Need”

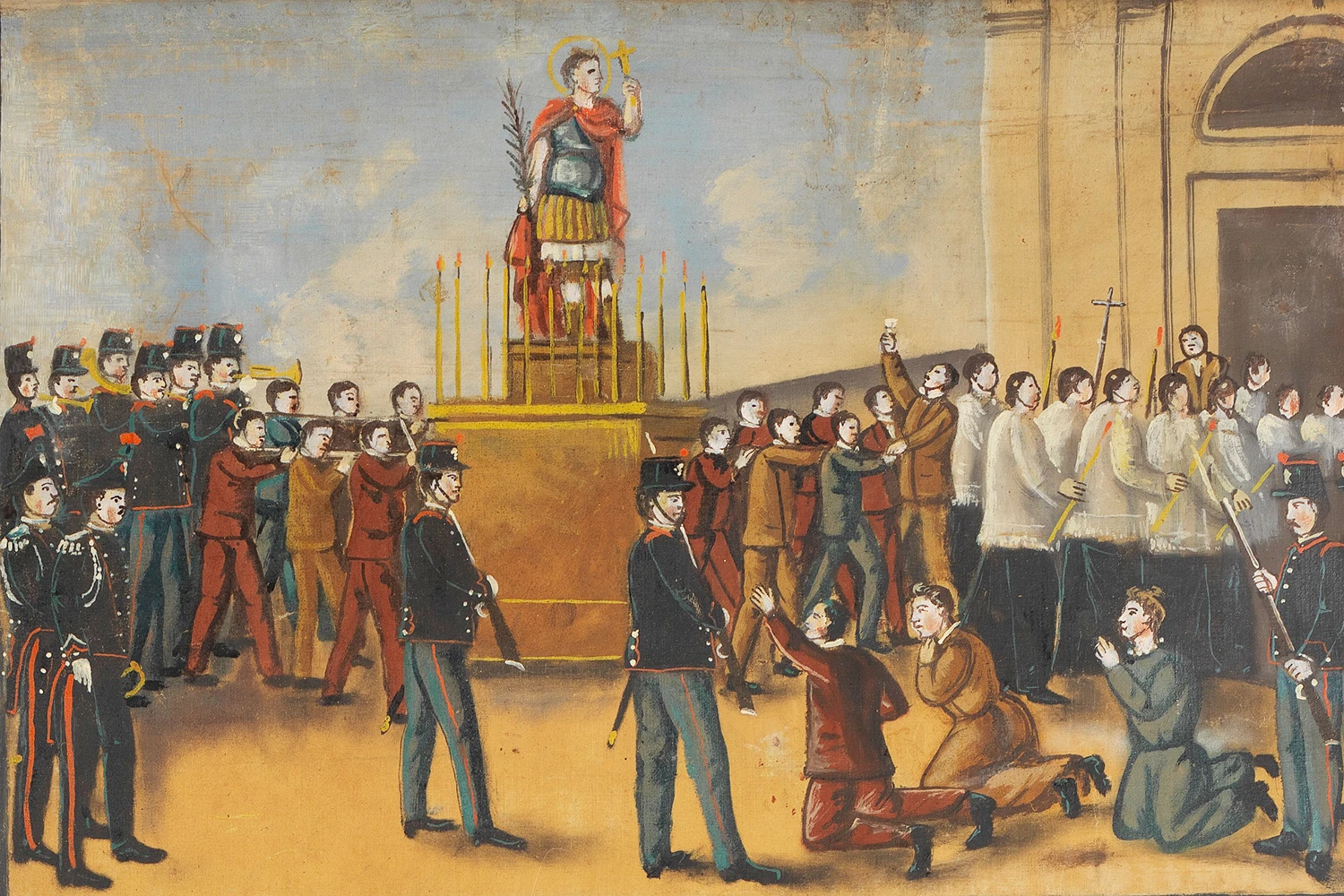

The Saint Who Refused to Delay is the object of a devotional cult that spans several continents. On tiny Réunion Island in the Indian Ocean, believers build roadside altars in Expedite’s honor, always painted bright red and decorated with small statues of the saint, where they’re part of an elaborate protocol of intercessory prayer and bargaining. In São Paulo, Brazil, worshippers crowd services on St. Expedite’s feast day to leave scribbled prayers at church altars imploring the saint’s help. (The Feast of St. Expedite is celebrated on April 19, just a few days after another key date for American procrastinators–tax-filing day in the United States.)

But the locus of devotion to St. Expedite in the United States is in Louisiana, where his cult draws on a syncretic mingling of Catholic and voodoo influences. Nowhere does it thrive more fully than in New Orleans, where it’s not hard to find prayer cards printed with ready-made invocations to the erstwhile centurion:

Saint Expedite,

Noble Roman youth, martyr,

You who quickly bring things to pass,

You who never delays, I come to you in need . . .

Or:

St. Expedite, witness of Faith to the point of martyrdom, in exercise of Good, you make tomorrow today.

You live in the fast time of the last minute, always projecting yourself toward the future.

Expedite and give strength to the heart of the man who doesn’t look back and who doesn’t postpone.

Today, one of the best-known statues of St. Expedite sits in a small church on the scruffy edge of New Orleans’s French Quarter, where the scent of spilled beer hangs heavy on the streets. Our Lady of Guadalupe Church is the city’s oldest, built in 1826 as a funeral chapel. Its statue of St. Expedite occupies a small niche in the back of the church, and when I flew to New Orleans to visit the saint, I found about a dozen intercessory prayers written on bits of paper and left at the base of the statue by visitors asking for Expedite’s help in some urgent matter or other–beating their drinking habit or escaping some legal difficulty or, of course, overcoming their tendency to procrastinate.

I’d been told that it was local custom for the devout to leave a pound cake by the statue as an offering to the saint. But that day I found none. It turns out that the task of cleaning up stale pound cake and other offerings from the foot of the statue belongs to Father Anthony Rigoli, the church’s pastor, known locally as Father Tony.

Before he came to Our Lady of Guadalupe 14 years ago, Father Tony hadn’t heard of St. Expedite. But once at work at the church, he quickly grew accustomed to the tour buses cruising by on Rampart Street, telling their version of the Expedite story: one day in the 19th century, a package arrived at the New Orleans church containing a statue of an unknown saint. Since the package bore only the postal instruction “expedite,” the mystery saint was soon given that name himself.

“People get confused about these devotions, because they can border on superstitions,” he said. Indeed, Catholic authorities concede that St. Expedite is an assemblage of myths and legends, which the early church deployed as a kind of fourth-century marketing campaign to broadcast its anti-procrastination creed. His image was supposed to persuade pagans of the need not to put off their salvation, to convert promptly, before it became too late.

Father Tony tried to clarify: “I don’t think saints answer prayers, but I do think Jesus does. When we ask someone to pray for us, what we’re really asking for is support. We all want to feel that support. So these devotions are really for our sake. And that’s okay.”

On The Other Side Of Procrastination, Optimism

In my Catholic grade school growing up, brilliance was tolerated but punctuality revered. Nothing was more important than being on time. The classroom clock was almost always positioned, not coincidentally, just below the crucifix that watched over us.

That obsession was a legacy from the early Christian church, where it was almost universally expected that the Last Days and Final Judgment were imminent, around the corner, sure to come sooner rather than later. The expectation drove some people slightly crazy. Every few decades or so, a frenzied panic would overcome large groups of believers. Certain of the need to repent before it was too late, they gave away all they had, formed messianic mobs, walked across Europe to visit holy sites, and launched violent Crusades.

The more I thought about this hagiography, the more I appreciated the mythic gravitas it brought to my commonplace habit. The story gave me an alternative way of understanding procrastination: More than just a matter of mood or irrational decision-making or poor time management, procrastination really can be a matter of life and death. All of us are aware of the clock ticking, of our time running out. But deep down we also hope that somehow, magically, the clock might make an exception in our case.

I have never prayed to St. Expedite, but I share his devotees’ optimism, their faith that good things will come. Procrastinators may be depressed, delusional, self-destructive, but we are also optimists; we believe that there will always be a better time than the present to do what needs to be done. Optimism is the quality most often overlooked in procrastinators. For us, tomorrow is always brimming with promise.

Even nonbelievers tend to think of procrastination in the dire terms that early Catholics did–as a source of anxiety, or a stain of failure. But sitting there inside Our Lady of Guadalupe, those things couldn’t have felt more distant. An elderly woman prayed a rosary near the altar. In the back of the church sat a few people who looked as if they might not have had anywhere else to go, loitering in the pews. I don’t know for a fact whether they, too, were optimists deep down, or even die-hard procrastinators. I didn’t think about that much.

It was quiet, and I had nowhere to go, either. The church ticked in the heat. For now, anyway, no one was paying much attention to St. Expedite.

This article is adapted from Soon: An Overdue History of Procrastination, From Leonardo and Darwin to You and Me by Andrew Santella Copyright © 2018 by Andrew Santella. Reprinted by permission of Dey Street Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.