While he worked in a lab as a PhD student, growing cells from berry plants that would later be used in pharmaceuticals or cosmetic manufacturing, Finnish researcher Lauri Reuter couldn’t stop thinking about something. “I always thought, what do these things taste like?” he says.

The other researchers–all from a pharmaceutical background–thought he was crazy to want to eat cell cultures. “You’re in a lab, you’re not supposed to put things in your mouth, obviously,” he says.

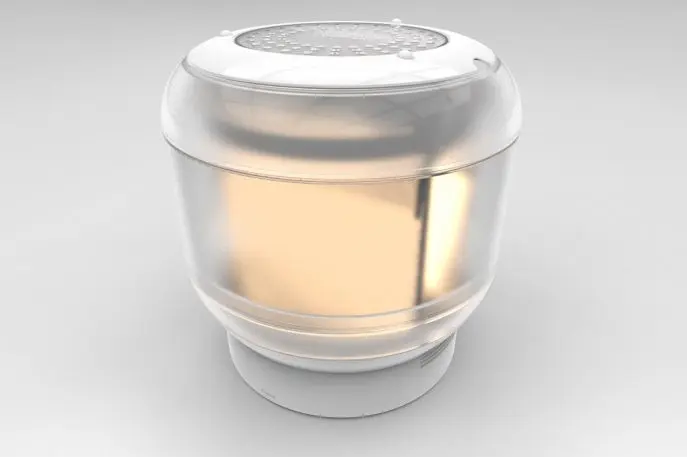

But the berry plant cells, along with being a source of complex biomolecules needed in manufacturing, are also nutritious. Reuter kept considering the idea, driven not just by curiosity but by the realization that in a world where traditional agriculture faces multiple environmental challenges, growing plant cells in a machine could be a useful way to produce food. Now, along with other researchers at VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland, he’s developing a prototype of a countertop vessel that could eventually grow edible plants cells in someone’s kitchen.

“You put in a pod, fill the tank with water, turn it on, and then it would start bubbling away,” he says. “You could harvest something like half a kilo of these plant cells in roughly a week. So it takes a bit longer than making a cup of coffee, but then again, if you would grow those berries in your backyard, it would take much longer, and the season would be only once a year. Now you can do it any day around the year, and in any place.”

The system could be used to grow plant cells, such as the arctic berries the lab has experimented with, that are difficult or impossible to otherwise cultivate. The arctic bramble, for example, produces only a single berry per plant, and is also becoming endangered. While the new machines can’t grow something that looks like a berry, they can grow a goo-like mixture of the plant’s cells that can provide valuable nutrition (the researchers are currently analyzing the nutritional profile in detail). While humans typically eat only a small range of plants–eight major crops, and some 20 fruits and vegetables–thousands of others could be eaten if they were easier to grow.

“I would argue that for most of our history, diets have been relatively diverse, but have narrowed recently,” Reuter says. In places where fresh food is particularly hard to access, the machines could provide a new source of a variety of nutrients. They could also expand the range of flavors possible in food; the researchers have also experimented with some plant cells, such as those from birch trees, that we normally wouldn’t eat.

In initial experiments, Reuter was disappointed in the taste–the berry plant cell cultures were brightly colored but had a very mild flavor. (Food technologists at the research center were pleased, since little flavor is better than a bad taste.) But through what he calls “gentle processing,” Reuter and the team were able to unlock more flavor. This process could potentially happen in the countertop machine.

In some cases, the flavors are unexpected. An early experiment with strawberry cells (undifferentiated cells from the whole plant, not the berry) tasted like lingonberries rather than strawberries. The team is currently working on developing the flavors, and solving technical problems like how to make a capsule of plant cells that can survive a journey to consumers. “That’s a completely new area of research,” Reuter says. “Nobody ever thought of putting plant cells in a capsule and sending it somewhere.”

The system isn’t yet close to coming to market; the researchers are still considering the best direction for the final product, and would have to partner with another company to manufacture it. The product would also have to get regulatory approval as a novel food. But to Reuter, it’s an example of the type of system that’s important to develop as traditional agriculture is increasingly strained by climate change.

“With climate changing in very unpredictable ways right now, it’s agriculture that will be hit the most,” he says. “That’s going to be a huge, massive problem. All our food is somehow linked to fields and the environment, and when the conditions on the field change, then we are in trouble. So we need to come up with new ways to produce the food in ways that are decoupled from the environment.”

Researchers at VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland are also developing similar systems for growing milk and egg proteins, and another system that produces food from CO2 and electricity. In a scenario where traditional farming no longer makes sense, these systems could provide most of someone’s diet, and the plant cell bioreactors could provide important vitamins and antioxidants.

“My dream would be to make this bioreactor farm that would have these several kinds of organisms, maybe one organism feeding the other, and then, in the end, you could produce a complete human diet in contained systems that could do it independently of the weather or the location or the season,” Reuter says.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.