Organized labor may be in a decades-long slump, but at least among the commentariat it appears to be making a comeback.

“Unions . . . get a bad rap,” Financial Times columnist Rana Foroohar has declared, maintaining that a “revitalized labor movement is exactly what the U.S. needs right now” to help boost the American economy. Even conservative Jonathan Rauch has called for a revival of unions–albeit in a new, modern form–to help address “the malaise and distemper afflicting America’s lower-middle class.” And Kashana Cauley, a writer for The Daily Show With Trevor Noah, suggested recently that millennials lead “the next labor union renaissance.”

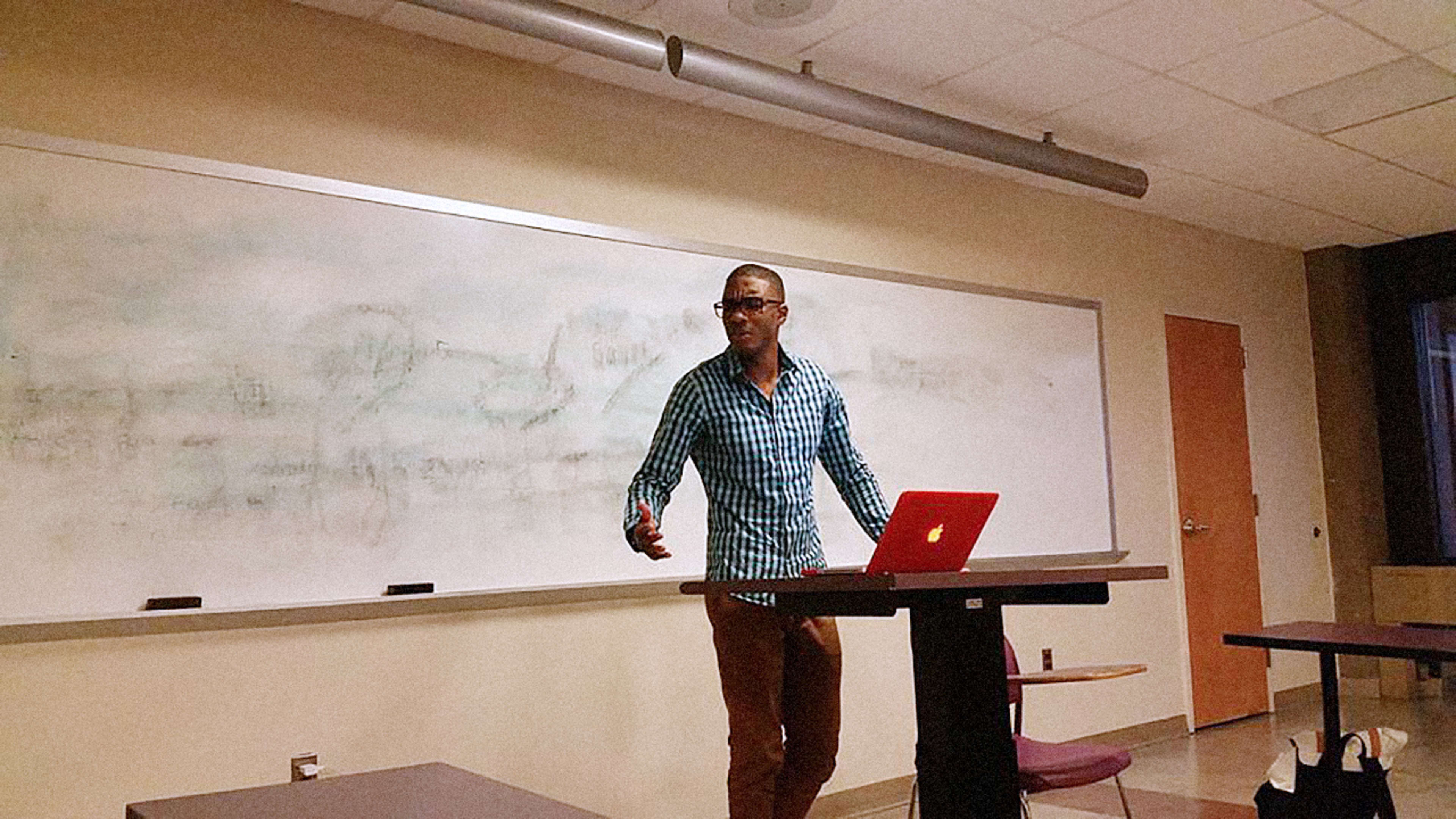

Larry Williams Jr.–at age 29, a millennial through and through–is doing his best to fill the bill. His means is a digital platform called UnionBase, which he’s positioning as both a social network for union members and an organizing vehicle for unions.

Already, other platforms–like those developed by OUR Walmart and Coworker.org–are giving employees a way to join together online and push back en masse against particular actions at a company. But Williams’s vision is much bigger: He wants not only to amplify workers’ collective voice but to actually facilitate collective bargaining on a grand scale.

“Workers in the 1930s led a union movement that changed the world,” says Williams, who serves as labor coordinator for the Sierra Club in Washington and has for the past five years been developing UnionBase on the side. “We can re-create that raw strength and use technology to leverage it.”

“The unsuccessful campaign in Canton,” the American Prospect observed, “epitomizes the immense challenges that weakened unions face as they try to survive, shore up strength, and expand in a globalized economy that is squeezing workers more and more.”

Across the country, organized labor has been on a long and steady decline. While more than 35% of the private-sector workforce carried a union card in the early to mid-1950s, only about 6% does today. Right-to-work laws have proliferated around the country.

Williams, however, is undeterred. “We have to stop talking about the problems of the past,” he says. “We have to start making the future.”

“Paper Stacked Up To The Ceiling”

For all of his passion, Williams didn’t set out to be a labor activist. As a student at the University of the District of Columbia, he held several jobs to get by–working the front desk at an apartment complex, at a Gold’s Gym, and as a reading tutor. He was interested in civil rights, but wasn’t exactly sure what kind of career to focus on. “I didn’t really have a plan,” he says.

Then in 2008, while still in school, Williams took a temp position at the Teamsters union, doing data entry. Immediately, he was swept away by the organization’s mission. “I was enthralled,” he recalls.

Williams, who was eventually brought on full-time at the Teamsters, began to read voraciously about labor history–about the battles that workers had waged over many decades to secure higher pay, good benefits, and better conditions. He also learned how the “spillover effect” from labor’s gains helped to lift up employees across the whole economy.

At the same time, he noticed something else: When it came to technology, most unions were still living in the Dark Ages. At the Teamsters, Williams says, he found himself looking up colleagues’ phone numbers in old-fashioned directories. “We had paper stacked up to the ceiling,” he adds.

So Williams decided to do something about it. He learned to code. And he began putting together a simple, searchable website that listed contacts for unions around the nation. UnionBase was born.

“It was just the basics of where to call,” says Louis Davis, then a fellow college student, who partnered with Williams on the project. “We were filling a gap.”

Over the years, with Williams spending about $25,000 out of his own pocket, UnionBase has been enhanced with educational material on labor and other features. About 10,000 people have visited the site since 2015, he says.

Facebook For The Labor Movement

The latest iteration–to be unveiled on Labor Day–marks a major step forward. It provides portals for union members to engage with each other and for their unions to engage with them publicly and privately. Williams likes to think of it as an early-stage Facebook for the labor movement.

This is particularly valuable because unionized businesses have been known to make it difficult for the rank-and-file to communicate by staggering their breaks and using surveillance. “What I like about UnionBase is that it’s a space to ensure that information can be shared even when employers restrict social interaction,” says Ben Speight, a Teamsters organizer in Atlanta.

For unions, this could prove to be an extremely cost-effective way to plug into groups of employees eager to organize. For workers, it offers a chance to jump-start the unionization process.

“Organizing a union through the use of online tools,” a 2015 report from the Century Foundation proposed, “would allow employees to band together in a more organic, grassroots effort that does not require outside help to get things started. . . . This is important because it would allow workers to organize wholly on their own terms, and it counters the standard anti-union message used by employers that they prefer to ‘deal with the workers directly,’ and that unions are ‘interlopers’ or ‘outsiders.'”

Can “Bureaucratic And Clunky” Unions Adapt?

Even with all of this promise, UnionBase faces significant hurdles.

For one thing, much of American business is fiercely resistant to being organized. Studies show that many employers will do whatever it takes—legal or illegal—to keep unions at bay.

This is one reason that Williams has gone to great lengths to try to make certain that UnionBase is highly secure, and that union members, nonunion workers, and labor organizations can use the site without fear of employer infiltration. “On Facebook, a lot of companies set up fake pages to trick workers,” Williams says. “That’s not going to happen here.”

Another obstacle may be organized labor itself, which is largely ill-equipped to take advantage of UnionBase. Many unions aren’t very good at messaging–and having a smart website won’t necessarily remedy that.

Some also wonder how many unions–which have been in a defensive posture for a long time and are often strained for resources–will be ready to spring into action and follow up if tapped via UnionBase. “A lot of unions are bureaucratic and clunky,” says Richard Freeman, a Harvard labor economist. “Change is hard.”

And then there’s a more fundamental–almost existential–issue. To some, attempting to revive the old union framework with new technology is the wrong prescription for restoring workers’ broad economic power.

Says David Rolf, president of Service Employees International Union Local 775 in Seattle: “It won’t be the legacy collective bargaining organizations of which I’m part” that will be “disruptive enough” to force corporations to give workers a larger slice of profits–and, by extension, give shareholders and top executives a smaller amount.

Rolf, widely seen as one of the most far-thinking leaders in labor, is instead advocating other models, including giving employees a greater say in how a company is managed through “co-determination”; advancing worker ownership; and establishing an “ethical workplace certification” program to point consumers to those businesses that treat their people well.

Yet Williams makes no apologies for UnionBase. “I’m all about fighting,” he says. “There’s a huge opportunity here”–even if it’s built on a system that reached its heyday more than three decades before Williams was born.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.