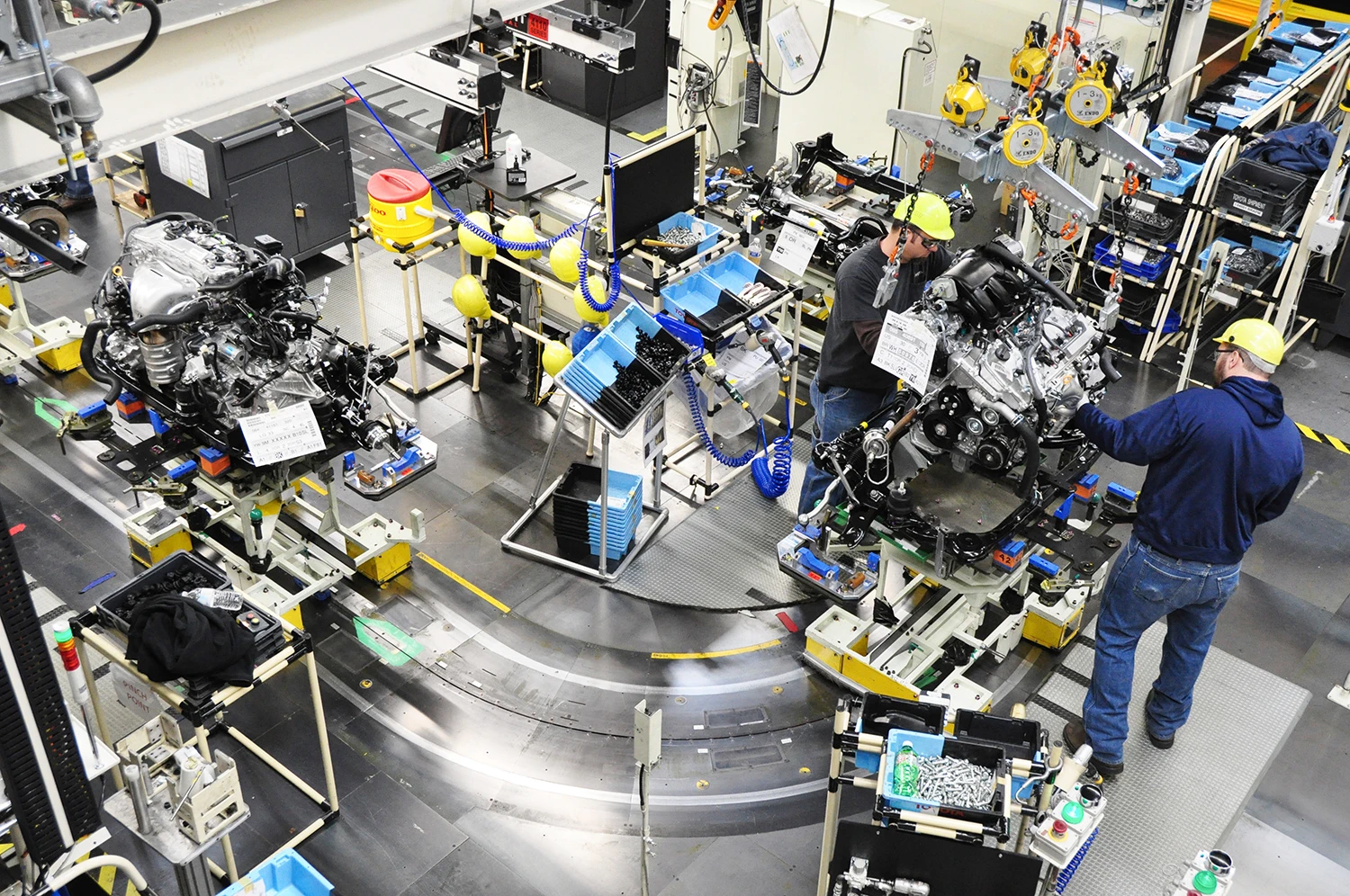

On the assembly line in Toyota’s low-strung, sprawling Georgetown, Kentucky factory, worker ingenuity pops up in the least expected places. For instance, normally in auto plants installing a gas tank is a tedious, relatively complicated procedure. Because the tank is so heavy, a crane usually positions and holds it against the skeletal frame while employees tighten its straps and bolts from under the chassis, a strained and time-consuming maneuver that requires keeping arms up in the air for long periods of time.

To allay the obvious shortcomings in this process, a group of Toyota workers designed an ingenuous device–a multi-armed piece of industrial machinery that in a single action lifts the tank in the air, places it in its crevice and reaches underneath the vehicle’s skeletal body to permanently attach the tank to the chassis. The process is fast, seamless, and ergonomically safe.

Freed from securing the bolts, the workers (the designers of this new device) would seem to be superfluous. However, that’s not the case at all. Indeed, the same number of employees as before are still at that assembly station. But instead of turning bolts in cramped crannies, they are doing the types of less obviously essential human tasks that manufacturers tend to eliminate when automation is introduced; namely, painstaking tactile and visual inspections to check and double-check for flaws on the tank and its connections and for holes or weaknesses in the critical fuel line.

The central role that people play in this corner of the Georgetown plant is repeated in varying degrees throughout the factory and exemplifies the uniqueness of Toyota’s manufacturing philosophy, which while still cutting edge continues to curiously nod to the past. Even as the automaker unveils an updated version of its vaunted production system, called the Toyota New Global Architecture (TNGA), the company has resisted the very modern allure of automation–a particularly contrarian stance to take in the car industry, which is estimated to be responsible for over half of commercial robot purchases in North America.

“Our automation ratio today is no higher than it was 15 years ago,” Wil James, president of Toyota Motor Manufacturing in Kentucky, told me as we sat in his office above the 8.1-million-square-foot (170 football fields) factory. And that ratio was low to begin with: For at least the last 10 years, robots have been responsible for less than 8% of the work on Toyota’s global assembly lines. “Machines are good for repetitive things,” James continued, “but they can’t improve their own efficiency or the quality of their work. Only people can.” He added that Toyota has conducted internal studies comparing the time it took people and machines to assemble a car; over and over, human labor won.

The Robotic Mystique

Such thinking seems unorthodox but it’s not surprising given Toyota’s well-known manufacturing system, which was first popularized in The Machine That Changed the World, an unlikely best-seller in the early 1990s written by three MIT academics. Despite its dry subject, this book had a radical impact inside and outside of the business community–for the first time, unveiling the mysteries of Japanese industrial expertise and popularizing terms like lean production, continuous improvement, andon assembly lines, seven wastes or mudas and product flow. With the publication of The Machine That Changed the World, it became de rigueur for every large and small manufacturer to at least give lip service to emulating Toyota’s production strategy.

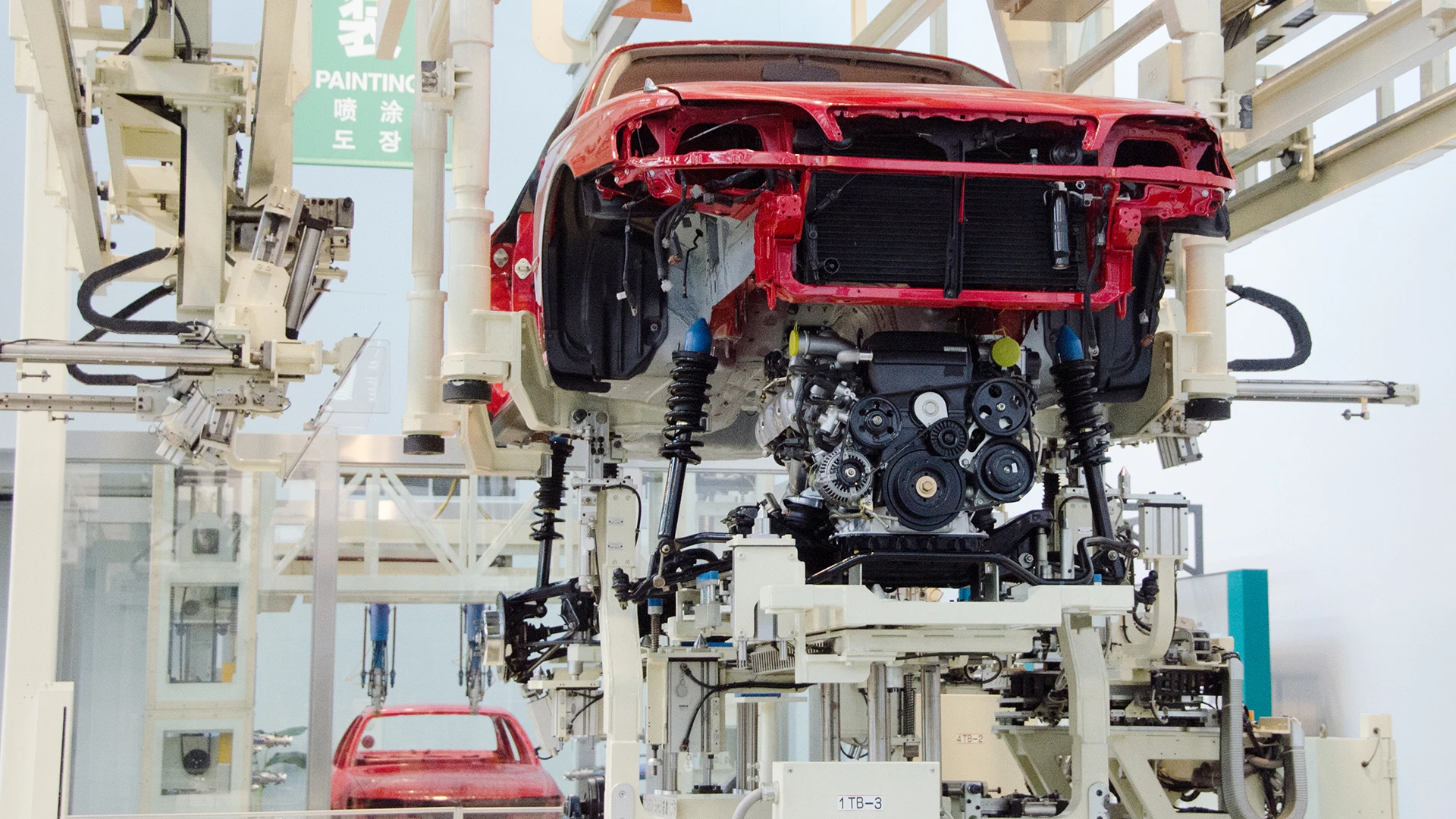

But as the decades past, you’d be forgiven if you thought that many of the balletic set of assembly line systems depicted in The Machine That Changed the World was anachronistic, especially the ones involving the contribution of human workers. Fundamentally, Toyota’s production principles were keyed to the notion that people are indispensable, the eyes, ears, and hands on the assembly line–identifying problems, recommending creative fixes, and offering new solutions for enhancing the product or process. Today, that idea seems quaint. In the industrial world now manufacturing prowess is measured more by robotic agility than human ingenuity. As an aspiration, lean is taking a back seat to lights-out–a manufacturing concept Elon Musk is championing for his Model 3 Tesla plant in which illumination will ultimately not be needed because the factory will be devoid of people . Even before we get there, auto companies like Kia–headquartered in Korea where the use of robots in manufacturing outpaces all other countries–are already claiming productivity improvements of nearly 200% from automation. Some plants have more than 1,000 robots–and less than a thousand people–on an assembly line.

Indeed, a nearly fetishistic appreciation of automation is ubiquitous these days. Dozens of articles, white papers, and books, written by respected thought leaders, executives, and consultants, depict an industrial future inevitably overrun by robots able to do the most sophisticated tasks at inhuman levels of efficiency. These are siren calls to most manufacturers whose growth plans are conditioned on cutting labor costs, which often make up as much as 25% of the value of their products. Some of the Pollyannaish views about the onslaught of robots foresee a period of unprecedented free time for individuals to cater to the whims of their imagination, turning us all into freelance artisans and entrepreneurs. Other, more sober forecasts worry about what people will do without the satisfaction of a job and the stability of a paycheck. Either way, a revolution awaits us, so goes the conventional wisdom. An oft-quoted Oxford University analysis predicts that over the next two decades, some 47% of American jobs will be lost to automation. In China and India, that figure is even higher: 77% and 69% respectively.

Links To The Past

But Toyota has forged a different path. The automaker, now jockeying with Volkswagen and Renault-Nissan for the top spot in worldwide sales, consistently generates industry best profit margins, often 8% or more. To maintain this performance, Toyota has eschewed seeking growth primarily through cost-cutting (read automation), but rather has focused on automobile improvements offered at aggressively competitive prices. Codified as the Toyota New Global Architecture, this strategy doesn’t primarily target labor to reduce production expenses but instead is weighted toward smarter use of materials; reengineering automobiles so their component parts are lighter and more compact and their weight distribution is maxed out for performance and fuel efficiency; more economical global sharing of engine and vehicle models (trimming back more than 100 different platforms to fewer than ten); and a renewed emphasis on elusive lean concepts, such as processes that allow assembly lines to produce a different car one after another with no downtime. In TNGA’s framework, robots are not the strategic centerpiece, but merely enablers and handmaidens, helping assemblers do their jobs better, stimulating employee innovation and when possible facilitating cost gains.

Kawai’s job now is to imbue TNGA with Ohno’s memory by bringing human craftsmanship back to the fore. Soft-spoken and unassuming, Kawai described the manufacturing philosophy he uses to achieve this as uncomplicated: “Humans should produce goods manually and make the process as simple as possible. Then when the process is thoroughly simplified, machines can take over. But rather than gigantic multi-function robots, we should use equipment that is adept at single simple purposes.”

A Series Of Elementary Innovation

Aspects of TNGA are being implemented in most Toyota factories around the world. But Toyota has invested in a $1.3 billion overhaul of Georgetown–its largest plant where 550,000 Camrys, Avalons, and Lexuses are produced each year–as TNGA’s pilot site before disseminating the new system globally. The imprints of Kawai and Ohno are already evident in large and small ways in the Kentucky facility. For instance, the outsized overhead conveyer belts that used to carry a steady stream of engines to the assembly line have been swapped out for moving pedestals that skate across the factory guided by electronic sensors in the floor. This new engine delivery system (which is, after all, merely a machine replacing a machine) accomplishes a series of manufacturing goals. By eliminating the complex web of conveyer belts, Toyota is able to downsize its plants considerably, essentially to one story from as many as three. That, in turn, results in substantial savings on construction, real estate, cooling, heating, and maintenance, some of the highest costs in managing a factory network.

And equally significant, freed of the conveyer belts, the assembly line workspaces are relatively uncluttered, cleared of pulleys, tubes, and pipes. As a result, assemblers can spend their limited amount of time with the automobile–usually less than a minute–completing their tasks and checking for defects while not wasting seconds navigating inelegantly around it.

A more rudimentary innovation in Georgetown that dovetails perfectly with TNGA tenets is the floating chair ,or raku seat (raku roughly means easy in Japanese). This assembly aid glides along rails in and out of the vehicle and then front to back inside the car, giving installers unimpeded access to difficult-to-reach spots like the dashboard console without having to bend or squeeze into awkward positions. The Toyota employee that designed this device patterned it after the moving swivel chair in his bass fishing rig–and used a seat from his boat to beta test the concept.

Besides its ergonomic benefits, the raku seat prunes seconds off of the production process, which is a persistent goal of Toyota’s manufacturing systems. Repeated across the assembly line, trimming small slices of time adds to up to meaningful productivity benefits. “In our world, we see work in 55-second bursts,” said Kentucky Toyota manufacturing president James. “And we challenge our workers to chop a second or more off if they can. If we gain back 55 seconds throughout the factory, we can ultimately eliminate a job and move that worker to another slot where they can begin the innovation process over again. Humans are amazing at finding those stray seconds to remove.”

Among the more compelling experiments underway in Georgetown is a training exercise meant to infuse the TNGA idea that automation should solely grow organically out of human innovation. To this end, assemblers were given a karakuri assignment–a lean management drill that requires workers to build a Rube Goldberg-inspired contraption that operates under its own force to improve a workspace activity. One team is reengineering the flow rack, the ubiquitous stand next to each assembly station that holds the parts needed for the local task. Currently, as shelves are emptied, workers have to manually set them aside and then replace them with a full bin of parts. The “modernized” version will instead rely on a combination of springs, ropes, and weights to navigate this task after a button is pressed. When this decidedly low-tech device is perfected, Toyota plans to use the prototype as the blueprint for a robot to emulate the process.

Toyota Emerges From A Debacle

TNGA, which Toyota expects will reduce manufacturing expenditures by as much as 40%, emerged from a dark period in the early 2000s when the automaker overeagerly attempted to outpace General Motors and Volkswagen as the world’s No. 1 vehicle manufacturer. Toyota has admitted that by juicing production growth too rapidly at that time, quality, manufacturing controls and factory productivity were allowed to lag. So much so that in 2009 Toyota had its first loss in 59 years (in part due to the global financial depression) and during the next two years recalled more than 10 million vehicles after a spate of sudden acceleration accidents. In 2014, Toyota agreed to pay a record $1.2 billion penalty to end a criminal probe by the U.S. Justice Department into its alleged attempts to mislead the public and hide the true facts about the dangerous problems with its vehicles. Toyota’s CEO Akio Toyoda apologized publicly and abjectly for the company’s failures and said the automaker was “grasping for salvation.” An internal soul-searching followed, which in turn led to the new manufacturing system and ultimately to Kawai’s appointment to lead its implementation and a return to craftsmanship.

As part of the TNGA rollout, Kawai has demanded that factories establish manual workspaces for critical plant processes, in some cases eliminating automation where it had already been installed during the period that Toyota overtaxed its production capacity. Kawai’s goal is twofold. First, to ensure that Toyota’s workers have the expertise and skills to manufacture a car by hand even if they wouldn’t be called upon to fully do so again. Kawai believes that without this body of knowledge assemblers become myopic, focused solely on their small part of the operation and blinded to their responsibility to design improvements for the larger team effort that are required to consistently produce high-quality vehicles. Worse yet, in this narrow outlook, workers often mistakenly see robots as replacements for people rather than basic tools that can be used to enhance factory performance.

Kawai’s second aim in replacing automated factory zones with people is to revisit with a clear mind–removed from the anxiety of a surge in production volume–whether robots have actually improved efficiency in individual plant activities. Some of the results of this experiment are unexpected. For instance, in a Japanese Toyota factory where workers have taken over forging crankshafts out of metal from automated equipment, subsequent innovations have reduced material waste by 10% and shortened the crankshaft production line by 96%.

Is The Robot Threat A Fantasy?

Toyota’s aversion toward automation is noteworthy for the obvious reason that the automaker is arguably one of the most creative and successful manufacturing companies in history, and has never followed the herd but rather set the course. However, beyond that, also worth examining more closely is the question raised by Toyota’s choice of direction: Do robots kill jobs or create them? Toyota, of course, would argue that while some manufacturers eagerly embrace automation and more will in the future, on a larger scale (and ironically in the more innovative and pioneering factories) robots are best used to precipitate more human plant activity rather than reduce it.

Recent analyses of employment data support this somewhat contrarian point of view. In one bit of research, James Bessen, a Boston College law professor, found that although automation has been increasingly prevalent in all types of services and manufacturing industries since 1950, in that time only one of 270 occupations categorized by the Census Bureau was eliminated by technology; namely, the elevator operator. Other jobs were partially automated and in many cases, automation led to more jobs, often higher-skilled positions at companies that used technology to design and develop new products and new ways to reach customers.

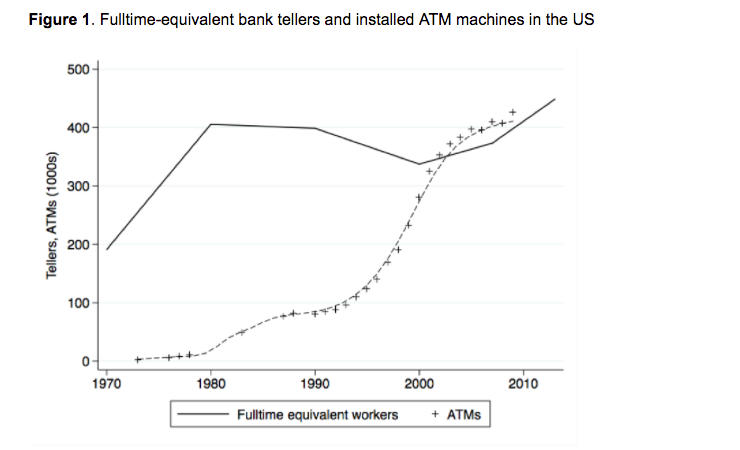

For instance, ATMs have radically altered consumer-banking habits, yet the number of branch employees has grown since money machines were first installed during the late 1990s. “Why didn’t employment fall?” writes Bessen. “Because the ATM allowed banks to operate branch offices at lower cost; this prompted them to open many more branches (their demand was elastic), offsetting the erstwhile loss in teller jobs.” And simultaneously, banks morphed into financial services companies, introducing an array of customized products that tellers were deputized to sell, giving behind-the-cage clerks the same opportunities for upward job mobility as deskbound bankers used to have.

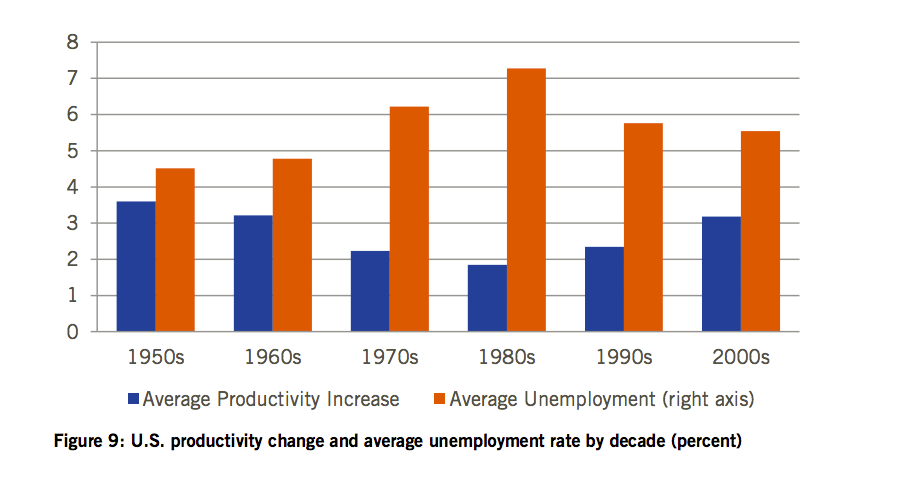

In addition, historically there is a direct correlation between productivity growth, which robots should naturally contribute to, and job creation not explained by population gains. In theory, companies able to manufacture products more quickly and efficiently will reinvest the money from higher sales in assets and innovation and, in turn, additional workers. Or they may lower prices, which drives more consumer spending, higher GDP, and an improved employment outlook. A trenchant study on this topic by the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation illustrated the relationship between productivity and employment by examining economic data of the post World War II era. ITIF found that in the 1960s, when U.S. productivity grew 3.1% per year, unemployment averaged 4.9%. [JR1] A couple of decades later, annual productivity growth had fallen to just under 2% and unemployment rates averaged 7.3%. And in the 1990s and early 2000s in the wake of the internet boom, annual productivity growth was nearly 3% again; in turn, the unemployment rate declined. From 2008 to 2015, productivity gains had ticked downward once more to only 1.2%; concomitantly, the rate of jobs creation has been sluggish compared to the pre-recession period.

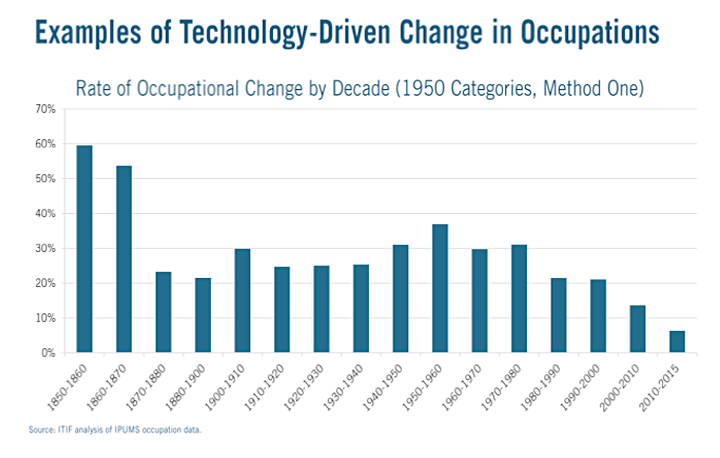

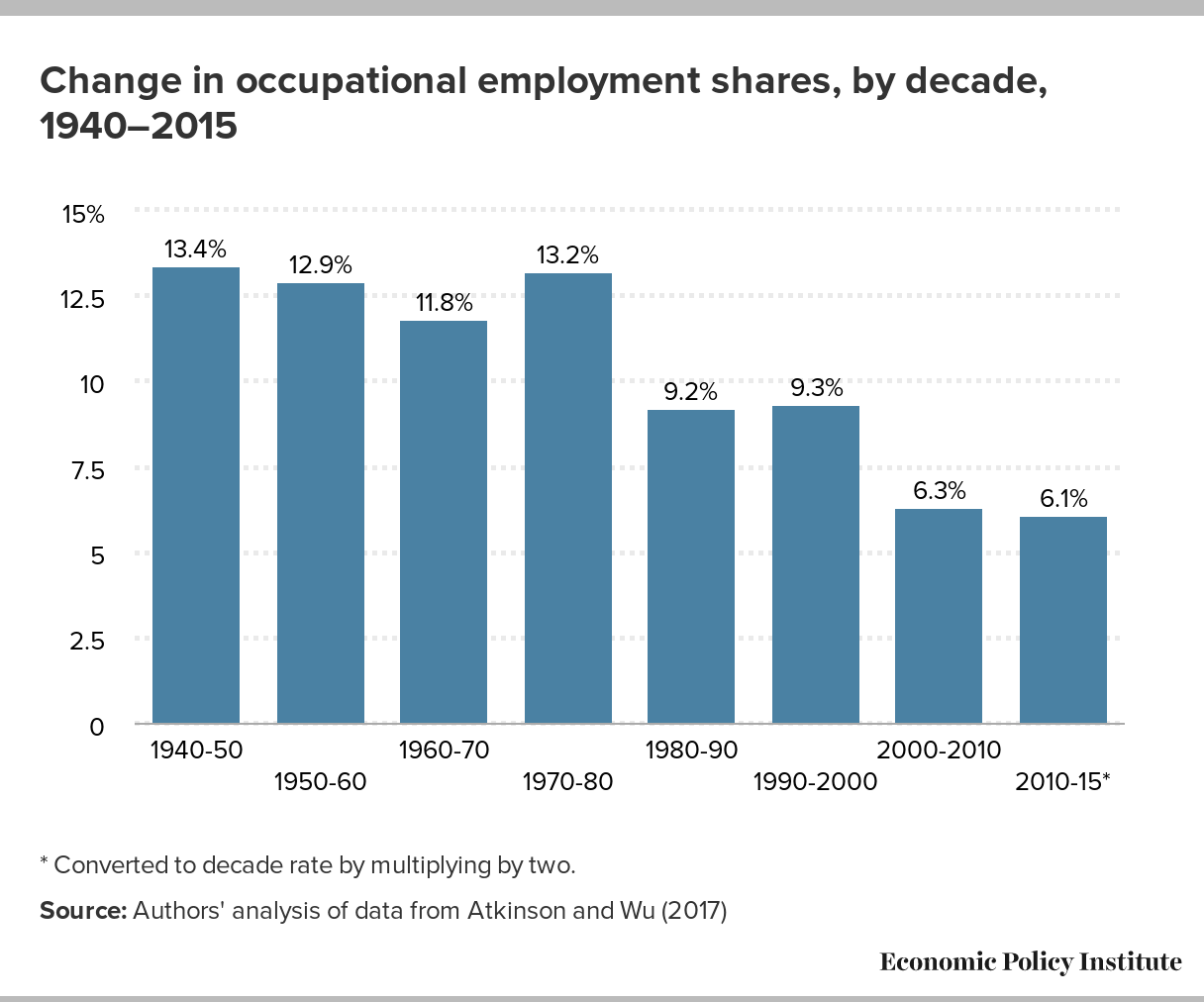

These productivity statistics lead to a few significant conclusions about automation today. For one thing, robots thus far do not make up a significant portion of manufacturing activities–responsible for only around 10% of the work in factories, according to some estimates–and companies that have embraced automation have yet to see significant gains from it since productivity growth continues to trend downward. Moreover, the effect that automation has had on employment has been muted. Another bit of data is worth mentioning in this regard: Workers are not leaving occupations as frequently as they did in past decades–the rate of occupational change in the 2000s is 45% lower than the 1940–1980 period and 33% lower than the 1990s, according to the Economic Policy Institute.

Robert Atkinson, ITIF president, believes that robots will in fact have a substantial presence in global factories before too long, although he doesn’t view automation as a threat to human jobs. He asserts that the productivity slump reflects a slowdown in innovation recently. Technology waves lasting as long 50-years have traditionally transformed society and revitalized economies but IT has stalled out, at the bottom of the S curve, Atkinson argues. “In the 1990s we went from dialup to 3 megabit broadband, that was transformative,” Atkinson says. “But going from 10 megabit to 50 megabit is not. Same thing with how much chips progressed in capabilities in the 1990s, but no more.”

As Atkinson sees it, the somewhat labored abilities of artificial intelligence are holding back robotic skills. That position is shared by John Launchbury, director of DARPA’s Information Innovation Office, who says that AI is within reach but yet a distance away from the type of contextual adaption that true factory automation requires; in other words, AI systems still lack cognition skills to understand and manipulate underlying explanatory models and identify and analyze real-world objects. According to Launchbury, today’s second wave AI systems are capable of statistical learning; based on millions of bits of data, they can separate one voice from another or a cat from a dog, among many other more complex distinctions. A contextual adaption system, though, “could say if a specific animal it sees with little more than a cursory glance has ears, paws, or fur and how they differ from another animal in the most minute ways,” he says.

When that level of AI is available, Atkinson argues, the next technological wave–the robot era–will have arrived. And annual productivity could increase to as much as 3.5%. “Which will create hundreds of thousands of jobs for people working with and around robots,” he says.

That, anyway, is what Toyota is counting on–or, better yet, cutting its own curve to make sure it happens.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.